The Peninsula

How Russia Hopes to Help North Korea Blunt the U.S.-South Korea Alliance

Published January 5, 2026

Author: Benjamin Young

Category: North Korea, The United States, U.S. Foreign Policy, US-Korea alliance

Amid North Korea’s ample support for Russia’s war efforts in Ukraine, Beltway punditry has largely seen the revitalized North Korea-Russia partnership as a “marriage of convenience.” Some analysts initially asserted that this was primarily a transactional relationship and a classic case of “the enemy of my enemy is my friend.” But recent sociocultural events suggest that the North Korea-Russia relationship is based not only on hard power but a strategic brotherhood that extends into the realm of soft power. Pyongyang and Moscow regard each other as companions in the ideological struggle against Western influence, which will facilitate a long-lasting partnership between the two governments.

The first clue in this ideological shift was that the first foreign visitors allowed into North Korea after the COVID-19 border closure were Russian tourists. Even before some Western diplomats were allowed to return to Pyongyang, the Kim regime had rolled out the welcome mat for Russian tourists. This was not a financially based decision. Historically, compared to the large number of Chinese tourists, Russian tourism to North Korea has been much smaller.

Kim Jong Un has invested considerable state resources into improving the country’s tourism industry. Many assumed that Chinese tourists would be the primary beneficiaries of Kim’s pet projects, such as the Masikryong Ski Resort. Some analysts speculated that Pyongyang’s post-pandemic economic rebound would be fueled by Chinese tourism. That is certainly not the case. North Korea now sees its economic future in the Russkiy Mir (Russian World).

North Korea’s deployment of soldiers to Kursk has captured most of the headlines, but it has overshadowed the significant sociocultural collaborations unfolding between the two nations. For example, in September 2025, a North Korean art exhibit opened in Moscow at the All-Russian Decorative Art Museum. This exhibit, which garnered international attention, featured paintings depicting North Korean and Russian soldiers fighting side by side.

Meanwhile, leading Russian cultural figures have recently visited Pyongyang. Russian ultra-nationalist pop singer, Shaman, performed in October 2025 in front of Kim at a concert in Pyongyang. Russia’s Minister of Culture Olga Lyubimova visited North Korea in June 2025 to celebrate the one-year anniversary of the signing of the North Korea-Russia comprehensive strategic agreement. During her visit, she personally met with Kim to discuss “broad and in-depth exchanges and cooperation.” Kim even alluded to the leading role that soft power plays in the North Korea-Russia alliance. “It is important for the cultural sector to guide the relations between the two countries,” he argued. Kim’s daughter also attended the meeting with Lyubimova, highlighting the importance of this partnership.

Beyond cultural exchanges in music and the arts, North Korean and Russian sports teams now meet regularly in competition. During a November 2025 visit to Pyongyang, the Russian women’s national soccer team played the North Korean national team, and a Russian under-seventeen club hockey team faced North Korea’s national squad.

Given these bilateral exchanges and state-sponsored visits, the Kim family regime trusts Russia beyond mere transnationalism. The two nations are steeped in the same ideological brew of ultra-nationalism, hyper-militarism, and illiberalism. North Korea has come to see the Russian Federation as a strategic bulwark against Western cultural influence. North Korean officials champion Russia’s military efforts against the West in pseudo-religious terms. North Korea’s Minister of Foreign Affairs Choe Son Hui referred to Russia’s war in Ukraine as a “holy war.”

In an effort to root out “anti-socialist” behaviors and “cultural pollution” from South Korea, North Korea has recently ramped up surveillance activities of its own citizens. Thus, tourism to North Korea largely remains reserved for Russians. This post-COVID development has allowed Russians unprecedented access to North Korean cultural sites and sporting events. In other words, the North Korean regime trusts the Russian people.

Meanwhile, the Russian Federation views North Korea as a central player in a multipolar world that pits “Eurasian” values against the West. Russia’s leading pro-Putin ideologue, Aleksandr Dugin, openly celebrates North Korea as a country free of Western psychological domination. He sees Pyongyang as fellow fighters in the ideological battle against Western decadence and arrogance (i.e, homosexuality).

For all its artillery shipments and troop deployments to Russia, North Korea has received relatively little in return. Although there have been reports of Russian military know-how flowing to North Korea, few of these claims have been substantiated. The cash-starved regime will someday seek to collect on its support.

But for now, the groundwork for long-term strategic cooperation has been laid, which will have far-reaching consequences for the U.S-South Korea alliance. With the deployment of troops to Kursk, it is clear that North Korea’s militarism is not restricted to the Korean Peninsula. This strategic maneuver shatters the stereotype of North Korea as an isolated and hermitic country that rarely emerges on the global stage. The U.S-South Korea alliance will need to consider that North Korea’s military adventurism does not end at the thirty-eighth parallel.

It also reflects a lack of imagination on the part of policymakers in both Washington and Seoul, who did not foresee such a rapid expansion in bilateral ties between Pyongyang and Moscow. The North Koreans should not be underestimated in their ability to persist and even thrive under unfavorable conditions. Moreover, possible joint North Korea-Russia military exercises on the peninsula should not be discounted. With its permanent seat on the UN Security Council, the Kremlin can shield and provide diplomatic cover for Pyongyang.

So what has North Korea actually gained so far from its rejuvenated partnership with Russia? Above all, it has received ideological affirmation. It has reinforced North Korea’s self-image as an anti-imperialist bastion that openly defies Western aggression. The shared ideological framing reinforces Kim Jong Un’s domestic legitimacy and lets the regime portray its relationship with Russia as part of a larger historic cause that builds on the regime’s anti-imperialist credentials, not merely a tactical wartime exchange.

Benjamin R. Young, Ph.D. has taught at Virginia Commonwealth University, Dakota State University and the U.S. Naval War College. He was a 2024-25 Stanton Foundation Nuclear Security Fellow at the RAND Corporation. He is now an Assistant Professor of Intelligence Studies at Fayetteville State University. He is the author of the book “Guns, Guerillas, and the Great Leader: North Korea and the Third World” (Stanford University Press, 2021).

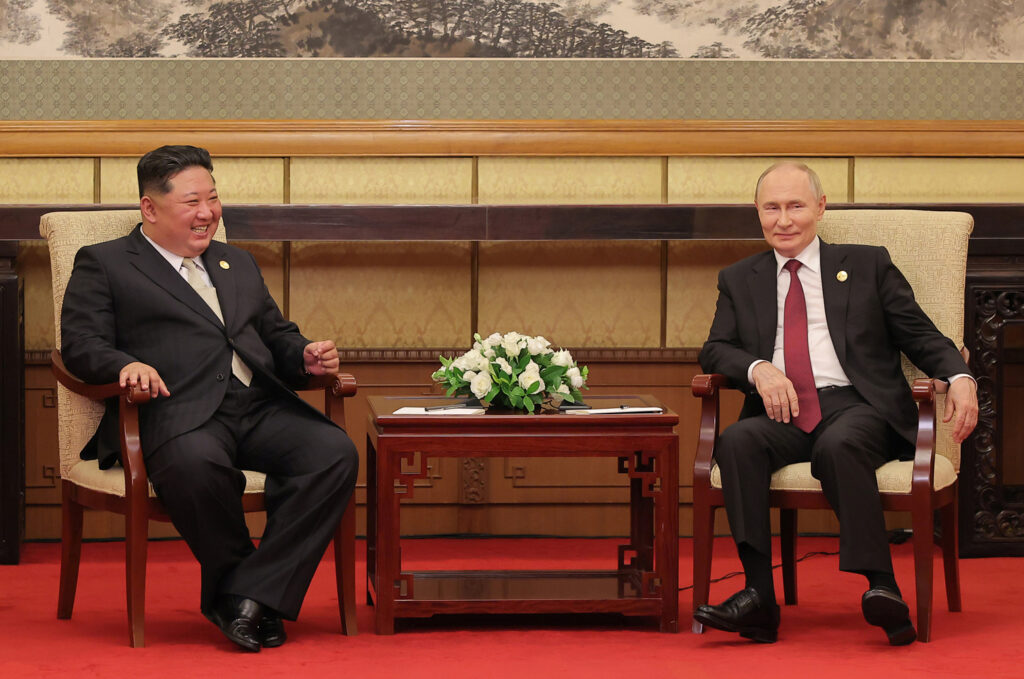

Feature image from North Korean state media.

KEI is registered under the FARA as an agent of the Korea Institute for International Economic Policy, a public corporation established by the government of the Republic of Korea. Additional information is available at the Department of Justice, Washington, D.C.