The Peninsula

The North Korean Wave Was Never a Symbol of Liberalization

Outside observers sometimes interpret the adoption of South Korean pop culture trends by North Korea’s state-sanctioned outlets as symbols of the regime buckling under the internal demand for change. The implicit hope is that cultural imitation of South Korea will lead to Pyongyang’s liberalization in other areas, particularly the economy and the political structure. People with this outlook may have seen Kim Jong-un’s recent excoriation of K-pop as a reversal in the regime’s openness to reform. However, North Korea’s increasingly diverse offerings in music, TV programs, cosmetics, and others were never indicators of broader liberalization.

In the digital age, South Korean music and dramas circulate throughout North Korea much more freely than before. USB drives with the latest K-pop albums and Korean TV dramas enter North Korea primarily through the Sino-DPRK border and are sold in North Korea’s jangmadang (informal street) markets. Spearheading the spread of these illicit materials, the so-called “Jangmadang Generation” – young people who were born in the 1990s – show increasing disaffection with North Korean propaganda. Some inside the country believe that this cohort’s rejection of the status quo threatens the regime’s long-term hold on power.

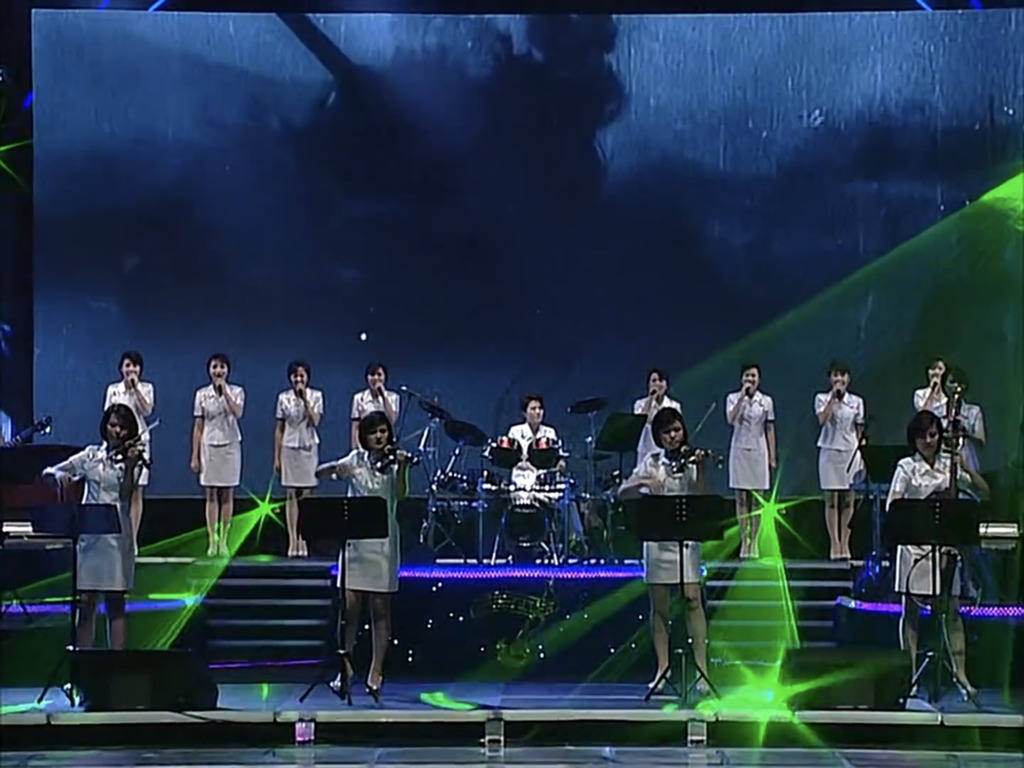

This may have contributed to Kim Jong-un’s decision to establish the Moranbong Band in 2012 soon after he became North Korea’s leader. In their early years, the women of Moranbong Band wore matching outfits with shorter-than-average skirts, showy jewelry, and noticeable makeup, all of which were uncommon in North Korea at the time. The band members also perform light choreographed dance moves while singing, and those playing instruments are shown to be using foreign name-brand products. While it’s not an exact copy of South Korea’s vibrant K-pop performances, the similarities of Moranbong Band’s earlier performances are noticeable when taking into consideration North Korea’s conservative social norms and style of dress.

Moranbong Band’s musical style is influenced by pop music, but its lyrics are overt propaganda that praise the leadership and regime initiatives. This contradiction of using foreign musical styles to spread propaganda hints at the intention of these projects. Instead of showing the country’s growing openness to the outside, the new music instead spotlights the regime’s principal goal of making its old message more appealing to the population.

To deal with the rising popularity of South Korean dramas, which found a following among both ordinary people and party cadres, the regime has also been producing its own dramas. Compared to Kim Jong-Il’s films that praised the DPRK leadership, dramas under Kim Jong-un are a subtler form of propaganda. They focus on daily life through light romance stories, school life, and periods in Korean history. Propaganda messages in these dramas center less around praising the leadership and more on enforcing social norms. The quality of North Korea’s dramas has increased as well, with more appealing outfits and sets, though the production value is not as high as their South Korean counterparts. The subtle propaganda messaging, episodic formats, and the focus on daily life make these dramas more comparable to South Korea’s popular TV dramas, and they illustrate how North Korea is benchmarking hallyu for its own ends.

The popularity of South Korean dramas has also created a market for makeup and fashion styles inside North Korea that the regime is attempting to capture. North Korea began its cosmetics production with the establishment of the Sinuiju Cosmetics Factory in 1949, and some of the state’s main brands currently include Pomhyanggi, Kaesong Koryo Insam, and Unhasu. In recent years, the North has sought to improve the quality of its cosmetic products, and the industry as a whole has received attention from Kim Jong-n and Ri Sol Ju who visited factories producing cosmetics in 2018.

Like South Korea’s major cosmetic brands, North Korean products come in lines that include toners, lotions, and serums. In at least one instance, the brand Unhasu has used an exact copy of South Korean cosmetic packaging: a cat-shaped powder compact from Tony Moly. To encourage both domestic and foreign sales, Pomhyanggi cosmetics are available for purchase through several online DPRK intranet retailers, as well as though Chinese online retailer Taobao. Despite these efforts, South Korean products are much higher quality and are still vastly preferred over North Korean cosmetics in Jangmadang markets.

Although it seems that the North Korean regime has in some instances adapted itself to keep up with hallyu trends, these changes are not an indication that the regime is becoming more liberal or is looking to open up to the outside world. Most notably, North Korea has recently adopted harsher punishments for those caught with South Korean media, including labor camp sentences of 15 years. A new law from January 2021 also criminalizes the use of South Korean terms, such as oppa, which has become popular through dramas. Under the January law, the regime threatens those who use South Korean language with a fine or imprisonment. Similarly, Moranbong Band was told in February to return to “traditional values” in an effort to move away from outside cultural influences, and their outfits have been military-inspired for several years. Furthermore, South Korean products smuggled in from China are still illegal.

While North Korea has adopted some South Korean trends in an attempt to extend the reach of the regime’s propaganda, it remains unwilling to engage in other liberalizing measures. The state remains hostile to open consumption of South Korean pop culture or any relaxation of social restrictions. Ironically, these will also hamper the regime’s ability to produce cultural content that is more appealing to a domestic audience.

Alexandra Langford is a former research intern at the Korea Economic Institute of America (KEI). All views expressed in this article are entirely the author’s own.

Photo from Wikimedia Commons.