The Peninsula

Pyongyang Worries About the Collapse of Its Won

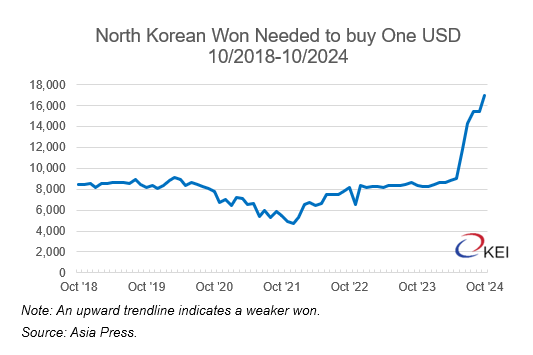

North Korea’s won has fallen in half against the US dollar since July for unclear reasons. An internal North Korean document collected by Daily NK blames perverse psychology for the trouble and warns that the won must be protected from further devaluation, suggesting high-level concerns of destabilizing inflation and a potential new banking crisis. The instructions, which issued dire warnings, are said to have been distributed by the cabinet, the government’s top administrative organ, to party and local government officials but not to the public.

Not Just Hyperbole

These concerns may not be entirely hyperbolic. The last major foreign exchange (FX) crisis occurred in 2009, as Kim Jong-un was preparing to take over the government from his ailing father. Rare street demonstrations even forced an official public apology from the North Korean government. This occurred as market pricing was expanding rapidly, the won was replacing ration tickets, and the state’s command economy system was eroding. Some in the North Korean ruling circles may remember that similar issues preceded the failed Tiananmen protests in China in 1989 and that money control problems contributed to the collapse of the Korean royal family in the late 1890s.

Dual Implications of Tight Monetary Policies

Kim’s best economic success to date has arguably been managing North Korea’s currency, fixing the dollar rate at close to 8,000 won in informal markets, and stopping inflation—something his father and grandfather were never able to do. He did this by using what could be considered standard capitalist measures: severely restricting the issuance of new cash and bank credit, casting a blind eye toward the surging internal use of US dollars and Chinese yuan, and balancing the budget without resorting to selling bonds. These measures—likened to a severely tight monetary policy without the use of interest rates—shoved the economy into a recession as state enterprises were starved of new cash. For the first time, the public was able to save money in banks and hold large denomination US dollar bills in their homes, withdrawing money from circulation and slowing inflation. Enterprises and even state agencies would have been unable to borrow, resulting in slower investment spending, a large part of North Korea’s GDP.

In 2015, after monetary stability had been achieved, Kim ordered financial authorities to modernize the banking system and promote won stability by inducing civilians to deposit their savings in state banks, offering high interest rates and guaranteeing that the won would no longer be deflated. The banks then could lend the funds, with interest, to state enterprises. As the won slowly returned to newly established “commercial” bank branches, foreign currency could be taken out of circulation. A near-normal capitalist banking system would thus develop, except that lending would be exclusively controlled by state enterprises—or at least that may have been the plan.

Trouble quickly ensued in 2017, however, as further nuclear tests led to additional sanctions from the UN Security Council. Export earnings collapsed as China jumped on board with imposing sanctions. Imports continued for a while, indicating a large current account outflow, with dollars and yuan leaving the country. The won remained glued to the dollar at 8,000, much like it would in a currency board system, but likely at a huge cost to the government. Pandemic-related border closures in 2020 fortuitously stopped the FX hemorrhage as imports were also stopped. The economy, however, was now starved of investment, which stalled exports.

Autarky and Currency Instability

In a key decision following the 2019 US-North Korea summit in Hanoi with then President Donald Trump, Kim decided to turn the economy inward, adopting an import substitution policy to rebuild domestic demand and limit the outflow of money. This partly worked, and the won even appreciated in value. But as border controls were slowly lifted in 2022 and 2023, North Korean imports of Chinese consumer products surged, whereas exports remained low, still stymied by UN sanctions and not prioritized in Kim’s plans. The trade surplus with China—a close proxy for North Korea’s deficit—again surged, which likely put pressure on the won. The outbreak of the war in Ukraine likely led North Korea to earn large sums in artillery sales to Russia. Additionally, its earnings from cyber theft and remittances from overseas North Korean workers and residents may have offset some of the rising trade deficit.

The North Korean document also says for the first time that the official exchange rate has been set at 8,900 won to the dollar—this after having been greatly overvalued for decades but largely ignored by the regime. Banks and money changers were ordered to use this new rate, apparently even after the market rate had soared. Details are publicly unavailable, but unifying the official and market rates is an important move to create a more rational monetary system, giving better market incentives to exports and imports. Setting the dollar a little higher might have been thought to diminish the inevitable skepticism that the won would again be devalued. If so, this did not work, and the public might have instantly thought another major devaluation was in the works. By dumping won and buying dollars, they could have forced that to happen. If they withdrew funds from their bank accounts to convert into dollars, this could have forced the central bank to relieve liquidity pressures by printing more cash, encouraging a further downward spiral in the won.

Difficult Reforms Needed

Immediate repercussions of the won’s abrupt fall are varied but can change quickly if the regime regains control. If not, momentum can build, causing the won to spiral down, with everyone bailing out and buying available dollars and yuan. The implications are as follows:

- There would have been big winners (mostly the rich who own assets in dollars or the Chinese yuan) and big losers (anyone who had borrowed dollars and now must pay back in inflated won). Social and even political repercussions would be inevitable.

- Potential disruptions in banks if depositors suddenly withdraw their won to buy dollars. Interest rates would likely soar on won accounts while dropping to zero on dollar accounts.

- Rational export and import decisions would be invalidated. Imports of grain will be more expensive to ordinary citizens, and market data shows that prices of rice and other commodities have already risen. Exports, on the other hand, will be more lucrative and might be incentivized.

- Most worrisome to the state are big jumps in prices for imported goods, which would lead to citizens’ demand for higher state wages and an unstoppable surge in overall inflation. This is likely what the regime hopes to thwart by producing these instructions.

The longer-term impact is no doubt a setback in Kim’s decade-long effort to build trust in the won and his creation of a modern economy. Solutions include shifting to an export-driven economy and focusing on products that are not sanctioned or poorly policed, such as hair products and artillery shells; a massive domestic sale of state property—or privatization—to pull in the won and limit inflation by running a state budget surplus; offering higher interest rates on won deposits, thus an even sharper turn to capitalism; or making a nuclear deal to eliminate sanctions on exports and resuming its sales of high valued coal and metal resources. Notably, North Korea has some of the world’s largest resources of zinc and other non-ferrous metals and rare earth minerals, which are now in great demand.

However, these solutions—in effect, opening the country up to the largely capitalist global economy—are not easy for an ideologically constrained regime such as North Korea.

William B. Brown is the principal of Northeast Asia Economics and Intelligence, Advisory LLC (NAEIA.com) and interim Senior Advisor at the Korea Economic Institute of America. The views expressed here are the author’s alone.

Photo from Shutterstock.

KEI is registered under the FARA as an agent of the Korea Institute for International Economic Policy, a public corporation established by the government of the Republic of Korea. Additional information is available at the Department of Justice, Washington, D.C.

For additional information, see:

William Brown, “Barely Afloat: A Depreciating Won Risks Financial Instability for Kim Jong-un,” Korea Economic Institute of America, August 28, 2024, https://keia.org/the-peninsula/barely-afloat-a-depreciating-won-risks-financial-instability-for-kim-jong-un/.

William Brown, “Is Tight Money and Sanctions Driving North Korea into Depression,” Korea Economic Institute of America, July 5, 2019, https://keia.org/the-peninsula/is-tight-money-and-sanctions-driving-north-korea-into-depression/.

“North Korean Economy Update,” Northeast Asia Economics and Intelligence, March 6, 2024, https://naeia.com/home-1/f/north-korean-economy-update.

“North Korea’s Monetary and Exchange Rate Pressures,” Northeast Asia Economics and Intelligence, September 24, 2023, https://naeia.com/home-1/f/north-koreas-monetary-and-exchange-rate-pressures.

William Brown, “UN Sanctions Continue to Devastate North Korean Trade,” Korea Economic Institute of America, February 8, 2019, https://keia.org/the-peninsula/un-sanctions-continue-to-devastate-north-korean-trade/.