The Peninsula

Will Gasoline Prices Shake Pyongyang?

By William Brown

Maybe not, given the still small use of cars in North Korea, but last week’s momentary doubling of prices at Pyongyang service stations, according to Daily NK reporting, on rumors China would cut off crude oil supplies in the event of a nuclear test, should have caught the attention of Kim Jong-un and his economic and security advisors. Diesel prices, apparently, behaved similarly. Prices had given up about half their gains by the end of the week amid no indications of either a nuclear test or an actual crude cutoff. Still, more than any other sanction imposed on the country, a cutoff of Chinese crude oil, translated into price hikes, angry customers, and slashed revenues, would cause big problems for Kim Jong-un as he pursues his byongjin line—the so far successful parallel development of the country’s nuclear and economic strength.

Looking forward, the price volatility suggests the North Korean landmass might not be the only thing shaking following its next nuclear test, and opens new avenues for affecting change in North Korean society. With widespread markets for commodities and services, and prices that apparently adjust to changes in supply and demand conditions, North Korea is in a far different place than either of Kim’s two predecessors could have imagined; more prosperous and productive, but also much more vulnerable. Speculation, driven even by rumors, could see a resumption of destabilizing inflation, a plunge in the value of the won, and trouble for the government reminiscent of the botched currency revaluation in 2009, as Kim was getting ready to take power. Kim seemed to have learned important lessons from that episode, and has managed to get a grip on inflation and currency devaluation, probably by allowing productivity enhancing market activities to continuously expand. But as a reminder of how little we know about the government’s ability to control markets, the volatility in gasoline and diesel prices stand in perplexing contrast to relative stability following China’s announced cuts in coal purchases just a month earlier, and the loss by now of about $1 million a day in national income. One would have thought this would spur traders to dump won and buy dollars but this, apparently, has not happened. At least according to the same Daily NK reporting.

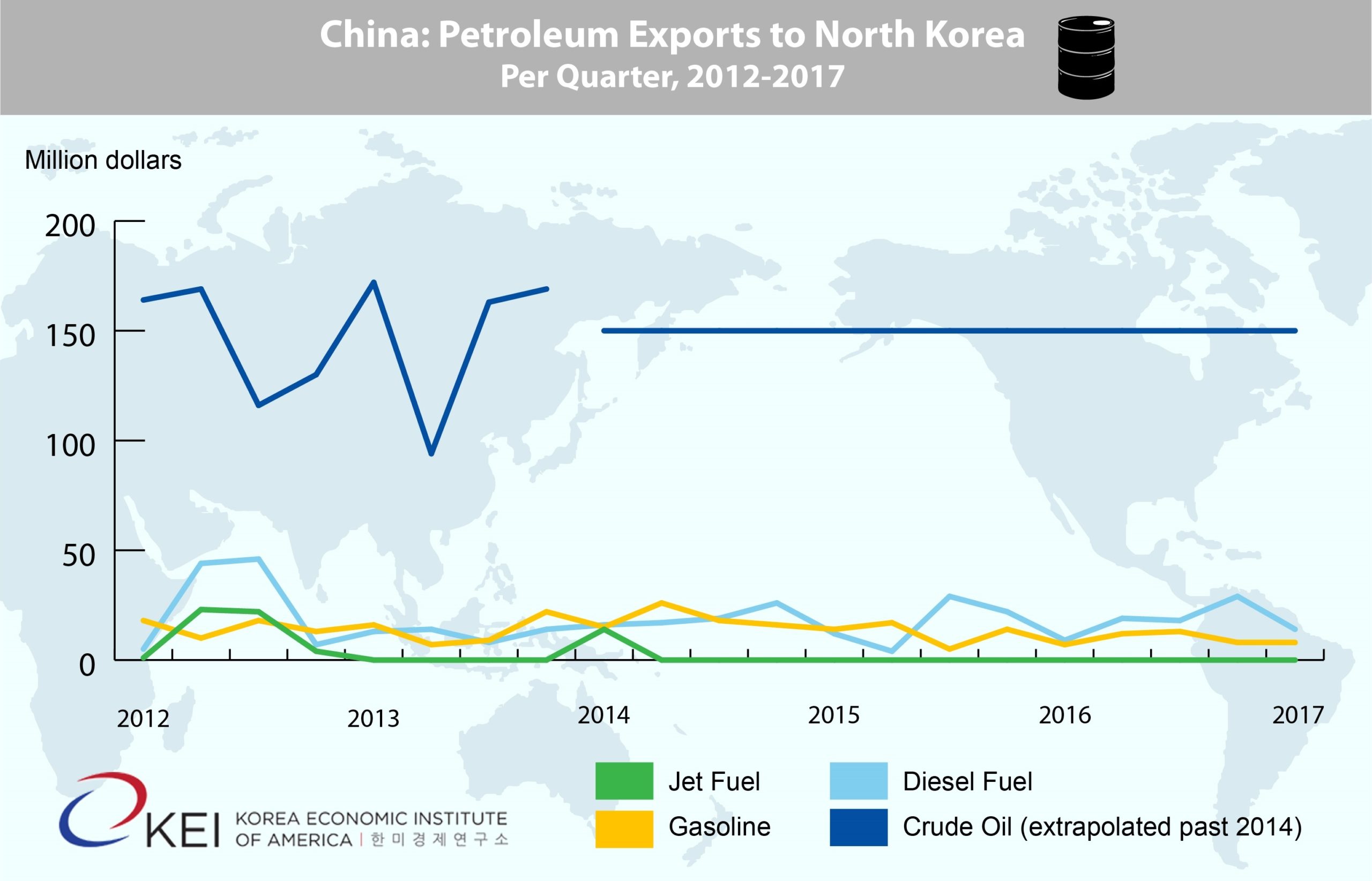

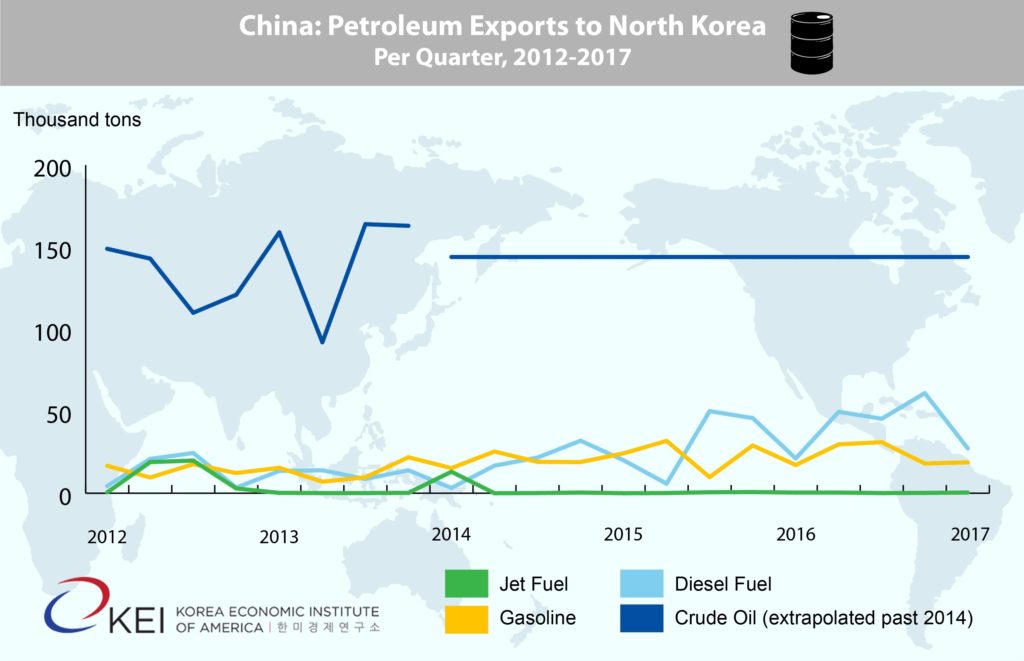

Tinkering with North Korea’s crude oil supply, and the income it provides, would be of far greater importance than the coal shutoff and would be treated very cautiously by Beijing. In a possible trial balloon in late April, Beijing allowed the first-ever hints of halt to its free delivery of about 50,000 tons of crude oil per month (valued at about $20 million at current Chinese export prices) if Pyongyang continues to test its nuclear weaponry, thus threatening to topple a longstanding pillar of the Mao Tse Tung – Kim Il Sung “lips and teeth” relationship.

Since the collapse of the Soviet Union, China has stood by North Korea, providing all the crude oil that the country refines and uses, in a small rail and pipeline served by a Chinese-built refinery across the border from Dandong in North Korea’s northwest, not far, ironically from the satellite launch site. The Soviets provided crude oil to a similar refinery just inside the northeast border, supplied by ship, but this has gone largely unused since trade collapsed in the early 1990s. Much smaller amounts of petroleum products are imported, again mostly from China but, aside from an annual gift to help with agriculture, these imports are probably on commercial terms. There are no hints that these product shipments would be subject to a Chinese boycott and, since they are profit driven, they would likely continue and even expand.

Chinese authorities have long been sensitive about the crude shipments, telling foreign academics and officials that this is a national security issue and thus any discussion is off the table. China was a net crude oil exporter when the presumed aid agreement was signed and oil flowed freely from the newly found Daqing oil field in Heilongjiang. But now China is a huge oil importer, and the supergiant oilfield is in decline, so the oil it gives North Korea is the same as if it were imported, and paid for by taxes on Chinese people, something Beijing probably does not want to advertise. And, by now, the uncollectable North Korean debt on this deal must have accumulated to tens of billions of dollars. Curiously, in 2014, Chinese Customs authorities stopped recording the crude exports even though sources indicate the oil continues to flow as normal. Placing the data off the books may have been meant as a warning that the supply is not endless and that Pyongyang needs to earn its way, or at least stop creating international tensions. These new warnings, however, are more direct and open to the public, guaranteed to add to the Chinese public’s musings over support to Kim Jong-un.

Though rich in coal and hydropower energy resources, and uranium, North Korea has no oil or gas resources and is entirely dependent on outside sources for transportation fuels. It has been adept at using its coal for petrochemical and fertilizer purposes, and much of the rail system is electrified, though in poor condition. With liberalized markets, demand for taxi, truck, and bus transportation has exploded in recent years, but is highly sensitive to price hikes and supply disruptions. In fact, the markets probably could not survive without gasoline and diesel-fueled transportation and agriculture would be severely harmed.

The rumors began when the unofficial English language affiliate of People’s Daily, Global Times, included an editorial on April 12 suggesting China might go along with new UNSC sanctions and cut crude supplies if North Korea tested a nuclear weapon[i]. This was followed on April 21 when a leading academic, and an authority on the subject, told a Japanese newspaper that China should consider such a cutoff. Soon thereafter, gasoline supplies in Pyongyang appeared to have been restricted and prices jumped from an average of 8,400 to 9,600 won per kilogram (about $3.00 a gallon at the unofficial but widely used exchange rate) to 17,625 won ($6.10) on 27 April, before falling back to 14,800 ($5.20) by May2, according to Daily NK. Diesel prices rose even more, from 4,720 to 17,150 won per kilogram. Although these prices seem high for a country as poor as North Korea, the market productivity engendered by a truck or a taxi, compared to a bicycle, is enormous and thus well worth the expenditure. Moreover, with no state subsidies, the prices must be higher than in neighboring China to induce the imports. No official statements confirm that China is willing to halt the oil shipments, and the price jumps might engender more concerns in Beijing, as well as Pyongyang, over potential instability.

Gasoline has long been dealt with inside the communist state’s fixed price system and thus transferred only by ration or through the central planning mechanism. Private use was strictly not allowed. But in recent years, as markets have sprung up for other products, gasoline has come to be sold at market prices, first by military or other government organizations which apparently have needed the cash—often U.S. dollars or Chinese yuan—and now, during the Kim Jong-un era, in relatively normal gasoline stations sponsored by several government and military government organizations which apparently are drawing on their state plan allocations or they are able to purchase products in China, sell them in North Korea, and make a profit. This has allowed a rapid increase in private automobile traffic, including many taxis and commercial delivery vehicles and some private automobiles. As compared to when all such transportation was by bicycle or bus, the gasoline use has spawned a huge rise in productivity and marketization. Whereas this commercialization has given a substantial boost to the otherwise still moribund, and sanction laden, general economy, security officials, and communist ideologs, must feel threatened.

Information is sketchy about where the gasoline comes from and how the private sector or the government organs earn the hard currency needed to import it. Chinese trade data shows a steady increase in gasoline shipments to North Korea, recently eclipsing a slow rise in diesel and other middle distillates imports. But these are still much lower than the crude oil shipments and, presumably, much of the gasoline now comes to the market via unsanctioned transfers from the refinery. This makes sense since North Korean state enterprises that receive their rations from the refinery are hard pressed to come up with the increasing amounts of money needed to purchase goods and services in the markets, and thus they must be tempted to sell, rather than consume, their planned oil allocations. This, of course, creates havoc for the planning system which seems to have largely broken down.

China would have several options should it want to use oil to penalize Pyongyang for a nuclear test. A short-term halt in crude oil shipments, a permanent end to the credit arrangement forcing Pyongyang to pay for the imports, or a cutoff of all crude and product shipments. Each would have different impacts and Beijing would likely try to decide which would have the most desired impact—deterring the nuclear program while not leading to instability. One way to do that would be to end the credit arrangement but, since it has become such a valued and important commodity, continue to allow or even induce more private trade in petroleum products. North Korea buyers would have to come up with more hard currency and would try to do this by increasing their private exports, so trade might even expand to the advantage of the Chinese and to the North Korean private sector. The impact on the North Korean government, on the other hand, would be severe as it would not only have to pay hard currency for its own considerable use of petroleum, but would also no longer be able to earn hard currency from its domestic sales.

Pyongyang, of course, could react by closing off private sales and use valuable hard currency to import petroleum for its own use. It would likely try but have a hard time finding a foreign supplier for the old Soviet refinery, which can be served by ocean tanker, perhaps in return for some of the plant’s output. Cutting private sales might be necessary, but it would go against the grain of Kim Jong-un’s policies to date. Whatever can be said about his stubbornness in pursing nuclear weapons, and in terrorizing his subordinates with selective executions, Kim has generally made good on his promise to push forward economic development. He inherited an economy with hyperinflation and a disintegrating domestic currency, but by allowing productivity enhancing markets to expand he has been able to control inflation and the won, at least for the moment All of this would likely be lost, however, should Chinese crude oil deliveries suddenly stop. In this context, even if short lived, the jump in gasoline prices must be enough to give him and his advisors pause over when to undertake the next nuclear test.

William Brown is an Adjunct Professor at the Georgetown University School of Foreign Service and a Non-Resident Fellow at the Korea Economic Institute of America. He is retired from the federal government. The views expressed here are the author’s alone.

Photo from Joseph’s photostream on flickr Creative Commons.