The Peninsula

What is Korea’s Energy Exposure to the Conflict in the Middle East?

The recent crisis in the Middle East raises questions about the impact it may have on energy access for the world. Faith Birol, the current head of the International Energy Agency, said that the Israel-Hamas war is “definitely not good news” for oil prices. Similarly, on October 30 the World Bank warned that oil prices could be pushed into “uncharted waters” were the conflict to extend further. All of this surrounds a first-time state visit by a Korean president to both Saudi Arabia and Qatar as Korea grapples with the question of what comes next. So how exposed is Seoul both directly from the conflict and in the risks from broader escalation?

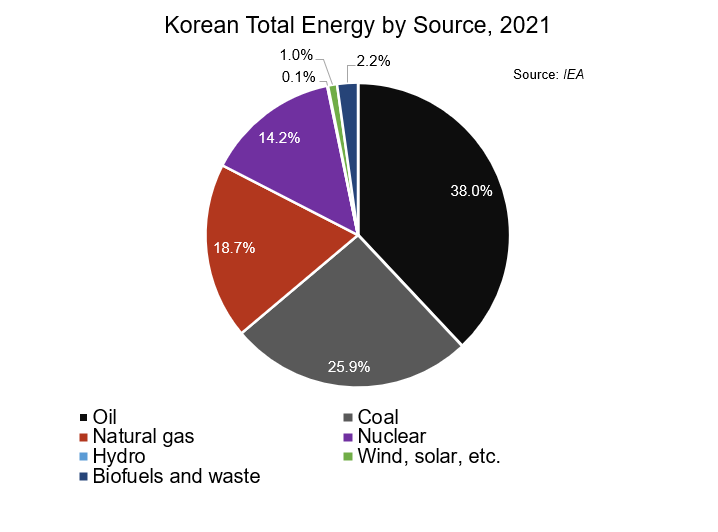

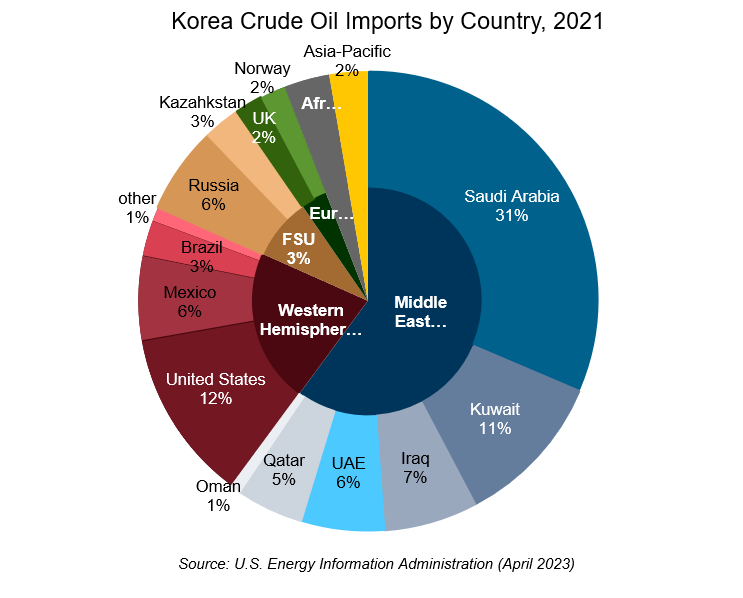

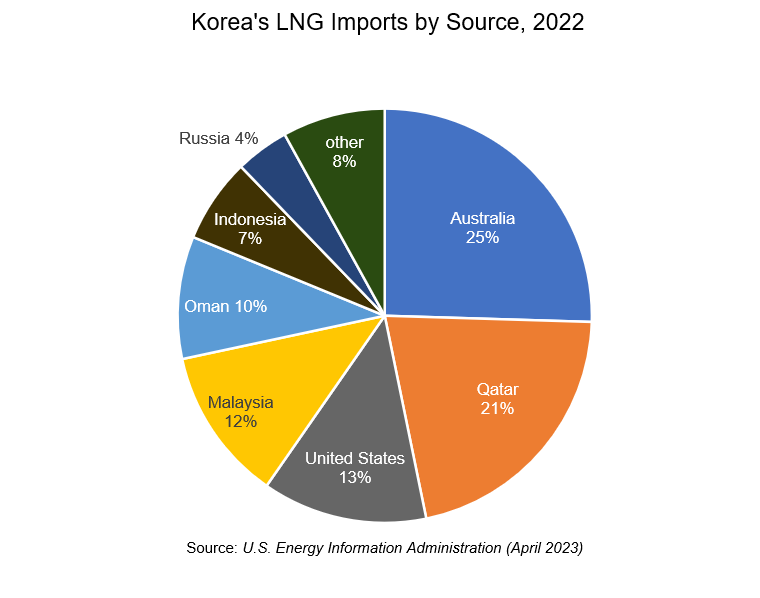

Directly, the conflict has had limited impact on Korea apart from a brief spike in global crude oil prices and their according effects on inflation, which in October stood at 3.8 percent year-over-year. On October 11, President Yoon Suk Yeol of Korea held an “Emergency Economic and Security Review Meeting” where he ordered for the Israel-Hamas crisis to be closely monitored and requested for “all efforts be made to ensure that necessary measures are taken quickly.” Finance Minister Choo Kyung-ho clarified on October 19 that “the Israel-Hamas clash has not caused major disruptions in energy supplies, and it so far has caused a limited impact on [Korea’s] financial market and the economy.” Larger issues would arise were the conflict expand to include Iran and accordingly shut off the flow of oil through the Strait of Hormuz. Even more so were the conflict to involve Lebanon, Syria, Egypt, or other Middle Eastern countries. Absent international pipeline connections, Korea relies on tanker ships to import much of the 98 percent of the coal, natural gas, and oil it uses for more than 80 percent of its energy portfolio. Along the same lines, Korea generally ranks among the top five largest importers of oil in the world, with more than 60 percent of theirs coming from the Middle East. Given all of this, it is no surprise that as part of Yoon’s recent visit to the Middle East a contract was signed with Qatar to provide more than 17 liquified natural gas (LNG) carriers for Korea.

Data sourced from International Energy Agency

Although any disruption to the flow of oil and natural gas in the region through conflict or embargo could have significant consequences for Korea’s import of energy, to some extent it would be tempered by the recent changes to the mix of Korea’s oil imports to eliminate Iran and include the United States as a major energy import partner. Prior to U.S. sanctions, Korea was the largest importer of Iranian condensate in the world. As a result of those sanctions, Korea has not imported oil from Iran since May 2019, and even when they did, Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Iraq, Qatar, and the UAE were generally more significant suppliers for Korea. Saudi Arabia’s role is also critical, both as an energy supplier for Korea and for the role they have in the ability to affect global price levels for oil through changes in levels of production. Consider the fact that in conjunction with the roughly $20 billion worth of agreements signed during President Yoon Suk Yeol’s state visit to Saudi Arabia and Qatar last month, Korea National Oil Corporation signed a deal with Saudi Aramco for Saudi Arabia to store and sell oil at the Ulsan storage facility, giving Korea priority access in the event of domestic supply shortages.

In December 2015, the United States repealed its ban on crude oil exports, marking a pivotal moment in the U.S.-Korea energy relationship. Subsequently, in 2017, the United States emerged as a net energy exporter. The transformation has had significant implications for both countries. Korea became the largest consumer of U.S. LNG in 2018, and beginning in 2021, the United States became Korea’s number two source of crude oil imports, trailing only behind Saudi Arabia. U.S. oil production is at an all-time high. The Middle East is not as significant as a supplier as it was in the 1970s. Accordingly, countries would be less exposed to Middle East disruptions than they were during the Yom Kippur War in 1973 when the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) placed an embargo on countries supporting Israel, leaving targeted countries frozen by energy shortages. Even though the 1973 embargo did not directly target Seoul, the memory of it pervades. It caused significant price increases across Korea, and the impacts were thought by some to be more severe on Korea than they were on the United States or Japan. Consequently, energy ties have become an increasingly vital element of the U.S.-Korea relationship, building a significant buffer from over-dependence on the Middle East.

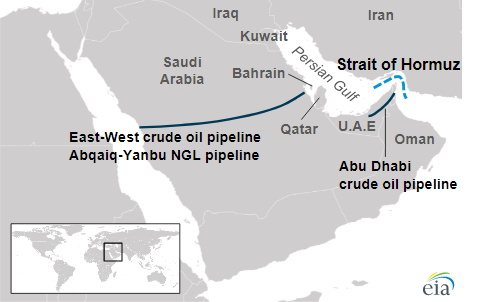

A key factor in Korea’s continued access to imported energy would be the safety and freedom of navigation for the tanker ships in the waters surrounding the conflict. For example, in 2021 a Korean chemical tanker operating off Oman was seized by the Iranian Revolutionary Guards Corps apparently in connection to Korea’s role in sanctions on Iran. Increased provocations would put the future of these types of ships in jeopardy. The Strait of Hormuz is one of the most important oil transit locations on the planet with 40 percent of all seaborne crude oil and 20 percent of LNG regularly passing through it. Iran has in the past threatened to disrupt the flow of oil through the Strait and doing so would expose Seoul’s longstanding vulnerability to the geopolitics of the Middle East. The Bab-el-Mandeb Strait connecting the Red Sea and the Gulf of Aden as well as the Suez Canal would be similar chokepoints in the event of a crisis.

While the conflict remains localized, at the very least, some argue that Hamas’s actions have brought the Iran-Israel proxy war to Israel itself, although both the United States and Iran have denied reports of Iran’s direct involvement in planning the attacks and Foreign Minister Hossein Amir Abdollahian publicly stated that Iran “is not pursuing the spreading of [the] war.” In any case, in the escalation of the conflict there is a possibility for Iran to get involved by blockading tankers affiliated with countries supporting Israel or tied with the United States operating around these straits.

U.S. Energy Information Administration, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Iran has already called on Organization of Islamic Cooperation (OIC) member countries to halt their oil exports to Israel, eerily echoing the 1973 embargo. And while OPEC itself has since publicly stated that it “is not planning to hold an extraordinary meeting or take any immediate action,” were an embargo called by Iran to extend globally, Seoul could find itself in the crossfire. Furthermore, provocations could extend beyond the Middle East. Cho Han-bum, a senior research fellow at the Korea Institute for National Reunification, pointed out to Voice of America of the possibility of North Korea forming an “anti-American front line” with Middle Eastern countries and Seoul has since gone on high alert for any possible warnings of North Korea taking advantage of the chaos.

Given that Korea is heavily dependent on imported fossil fuels to meet its energy demands, the crisis in the Middle East could serve as impetus to hasten their transition to net zero emissions by 2050 or 20 percent renewables by 2030. Likewise, Faith Birol believes the conflict could “further accelerate the energy transition around the world.” Were oil prices to reach unprecedented levels, such as in excess of $150 a barrel as the World Bank has warned, the long-term need to transition to renewables would be critical. Doing so would require sustained investment in renewable energy projects and government policies which gradually wean off the reliance on imported fossil fuels. With the return of conflict to the Middle East, there is no time like the present.

Tom Ramage is an Economic Policy Analyst at the Korea Economic Institute of America. The views expressed here are the author’s alone.

Photo by Kim Yong Wii on the Republic of Korea’s official Flickr.