The Peninsula

The Media Cultures that Shape News on North Korea

Published June 26, 2020

Category: Culture, North Korea, South Korea

By Andray Abrahamian

A month ago we ended a thrilling rollercoaster news event that helped temporarily distract us from coronavirus news: the health of Kim Jong-un. This story was due to some specific features of newsgathering and reporting on North Korea. With a bit of hindsight on that maelstrom, it might be worthwhile to zoom out and take a look at the media cultures that help shape North Korea news more generally, when there isn’t necessarily a “BREAKING” headline to get our attention.

Three media cultures create the majority of English-language news about North Korea: the United States, United Kingdom and the Republic of Korea. All three have unique characteristics and generate news in specific ways to meet particular goals and standards.

In the United States, news production rests on the foundational value of objectivity, though that has come under strain in the past decade. But this principle isn’t applied evenly, of course. One area in which the objectivity norm is less robust when news covers foreign policy issues generally and war/conflict in particular. The United States is, of course, in conflict with North Korea.

In Britain, “rather than objectivity, notions of truth, independence and ‘fair play’ held greater appeal”, according to one scholar [1]. Partisanship is allowable, so long as the subject is dealt with equitably and rationally. When the subject is deemed to be acting wholly unfairly, however, the requirements for fairness in news coverage are understandably diminished. North Korea as a news subject finds itself in this position, as does, say, Dominic Cummings. This is particularly true for British tabloids, which pursue “righteous causes” with a vigor largely unseen in American media.

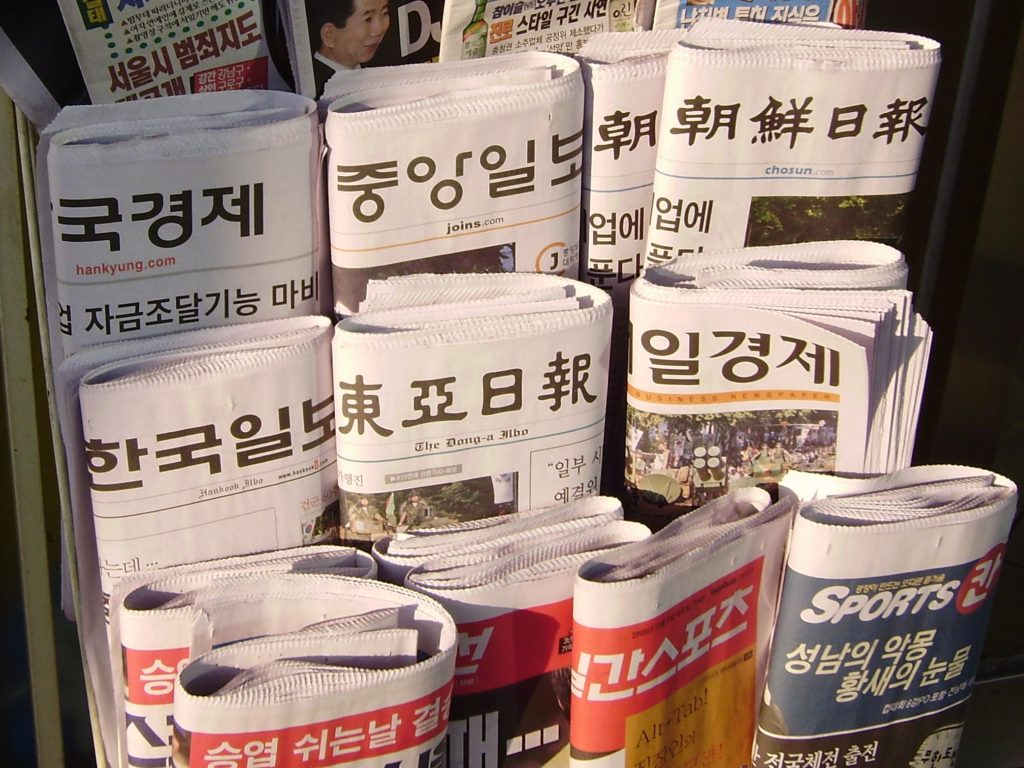

South Korea finds its news media embedded in a politicized and polarized environment. With a relatively short history of media freedom, large media companies tend to cleave closer to the state than in the other two countries. That state that is involved in an ongoing structural competition for legitimacy with its Northern neighbor, even when the government in Seoul is pursuing a policy of rapprochement.

These media cultures agenda-set for reporting worldwide on this topic. The United States is a media hegemon, whose media outlets command the attention of media in other languages. The UK is home to several agenda-setting media outlets, notably the BBC, the Times and the Guardian. South Korea is less influential globally, but produces a great volume of news about North Korea, often translated into English.

In the United States, as noted, the objectivity norm is reduced when covering foreign affairs. This is partly because media are reliant on official sources for content. (One study from the 1970s found that 75 percent of front-page stories on the Washington Post and New York Times depended on official sources.) The U.S. government can therefore present the information that is to constitute the news story and then simultaneously give the official opinion on it, framing the information from the beginning. If a journalist can find an opposing view, it tends to remain a subordinate “counterpoint” in the binary relationship between the two.

This doesn’t mean media are simply complicit in how officials frame foreign affairs and conflict. As Daniel Hallin puts it, “officials, in their efforts to control political appearances, necessarily challenge the autonomy of the media, and journalists naturally resist” [2]. But, as Michael Schudson, another media scholar, notes: “the media are obligated not only to make profits but to maintain their credibility in the eyes of readers,” as well as “expert and often critical sub-groups in the population, particularly in Washington, D.C.” [3].

This is an important frame and might manifest itself, for example, by describing North Korean acts as “saber-rattling”, while the US and allies conduct “shows of force”. This is easy to slip into. After all, if you ascribe to small-l liberal values and a liberal world order, perspectives favorable to Pyongyang are usually fundamentally opposed to both American values and strategic interests. How does one find an objective viewpoint on such a country and its policies?

That fact that the DPRK doesn’t respect human rights and individual rights in the same way as western democracies also challenges the “fairness doctrine” of British media. This can happen with conservative, establishment press like The Economist, which famously had a cover of Kim Jong Il captioned “Greetings, Earthlings!” and bid him farewell when he died with a self-referential “Farewell, Earthling’s”.

UK tabloid news outlets are even more likely to mock North Korea. When The Sun snuck two journalists onto a tour of North Korea in 2012, “tricking” the regime, they noted that apartments in Sinuiju were “a sham, they were all windowless and empty. Despot Kim Jong-il had ordered the ‘homes’ to be built to make it appear to the Chinese that North Koreans were living well.” People were of course “zombie-like”. They also produced commentary about a “glum” circus: “The Sun’s shocking pictures expose the despotic regime’s everyday cruelty that will outrage animal lovers.” Still, the headline: “North Korea’s got Talent: Animals Made to Skate in Secretive State” is pretty amazing.

These descriptions are dubious and the point about the apartments manifestly nonsense. The point here is fairness becomes unnecessary when describing a place that is so alien, difficult and visits all manner of woes on its own citizens. And also on bears, who I agree should not be forced to skate.

Finally, South Korean media culture fits into what Hallin and Mancini call the “polarized pluralist model”. In this model, the processes that disembedded news media from political parties, interests and the state has not taken place. Pre-democratic South Korea has left a legacy wherein the expectation of cooperation between media and government is high. The government also has more leverage over news organizations than in the UnitedStates or UK.

There is a conservative press and a progressive press, both of which favor different approaches to North Korea, though overall within the framework of an alliance and good relations with the United States. The DPRK is a competitor state, after all, even if a pro-engagement administration like the current one is in power.

Along with this news-industry model, the specific news culture allows single anonymous sources to be the basis of a story, something not really possible in the United States or Britain. News stories can be much more “rumor-y” in Korea in general.

The nature of government leaks and anonymous source stories on North Korea, of which there are many, does change according to which kind of government is in power. Under the previous two conservative administrations, the stories pushed in the direction of the media tended to emphasize instability, human rights violations and deprivation. Under this progressive one, stories are more likely to emphasize stability, reasonable leadership and areas where compromise might be possible. What matters for English-language news is these are the pool of leaks that get picked up by the South Korean press, then sometimes re-interpreted by western outlets.

Ultimately, none of this is about what is true or false per se. But as media consumers being aware without being hyperbolic – no need to scream “fake news” or any of that nonsense – is important as we attempt to understand a difficult and complicated country.

Andray Abrahamian is a Non-Resident Fellow at the Korea Economic Institute, Visiting Scholar at George Mason University Korea, and Senior Adjunct Fellow at Pacific Forum. The views expressed here are the author’s alone.

Endnotes

[1] Mark Hampton, “The ‘Objectivity’ Ideal And Its Limitations In 20th-Century British Journalism,” Journalism Studies Vol. 9, No. 4, (2008): 477.

[2] Daniel Hallin, The Uncensored War (New York: Oxford University Press, 1986), 7

[3] Michael Schudson, The Sociology of News (New York: Norton, 2003), 40.

Picture from flickr account of Eli