The Peninsula

The Impact of U.S. Trade Policy on South Korea

Published April 29, 2025

Author: Randall S. Jones

Category: Indo-Pacific, United States, US-Korea alliance

President Donald Trump said on February 18 that he intended to raise automobile tariffs on all U.S. automobile imports. He followed through with this plan on March 26, announcing a 25 percent automobile tariff that took effect on April 2, making engines, transmissions, powertrain parts, and electrical components, as well as fully assembled cars, all more expensive.

Tariffs on auto parts will impact South Korean automakers, as they rely heavily on imported parts to assemble their cars in the United States. It is estimated that Hyundai and Kia acquire 12 percent and 20 percent, respectively, of their parts in the United States or Canada.

President Trump’s tariff announcement came the same day that Hyundai Motor Group opened its third U.S. production site, a USD 7.6 billion electric vehicle plant in Georgia, and two days after it announced it would invest another USD 21 billion in the United States. Around USD 9 billion of this will go toward expanding car production, and another USD 6.1 billion will go to the steel industry, where imports are also subject to a 25 percent tariff.

Profound Effects of Protectionism

The protectionist policies of the Trump administration have profound implications for both the United States and Korea. Hyundai and its luxury line Genesis, along with Kia, sold about 1.7 million vehicles in the U.S. market in 2024. Of these, 700,000 units were produced in factories in the United States, with the remainder exported from Korea and Mexico. Passenger vehicles have topped the list of Korean exports to the United States since 2011 and accounted for 8.6 percent of all vehicles sold in the United States in 2024, generating almost half of Korea’s total automobile export revenue. Korea was the third-largest exporter of cars to the U.S. market (Figure 1).

Higher tariffs are likely to lead to higher inflation and slower growth, according to Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell. Auto tariffs will likely generate inflation, as has been the case with past protectionist measures.

For example, U.S. tariffs on washing machine imports in 2018 resulted in a 12 percent increase in the price of washing machines in the United States, with only a minimal impact on employment. The impact of tariffs on the price of imported Korean cars will depend on their price elasticity of demand. If the protectionist policy for cars remains in place, it would weaken the competitive pressures that drive innovation and efficiency gains, making it difficult for U.S. car producers to keep pace with foreign producers.

Figure 1. Korea accounted for about one-sixth of U.S. car imports in 2024

Note: The HS code for cars is 8703. The countries shown in the figure accounted for 99.5 percent of U.S. car imports in 2024 | Source: U.S. Import Data & Top Import Trade Partners – U.S. Imports Insights

The tariff hike also affects GM Korea, which has seen exports to the United States increase by 2.4 times over the past five years (Figure 2). In 2024, it accounted for 30 percent of sales of Korean-made cars in the United States. GM Korea employs around 11,000 workers in Korea, and 85 percent of its exports go to the United States. Higher entry barriers to this market put the future of GM Korea in jeopardy.

Figure 2. GM Korea accounts for nearly a third of sales of Korean-made cars in the United States

Source: GlobalData

The Potential Impact on the Korean Economy

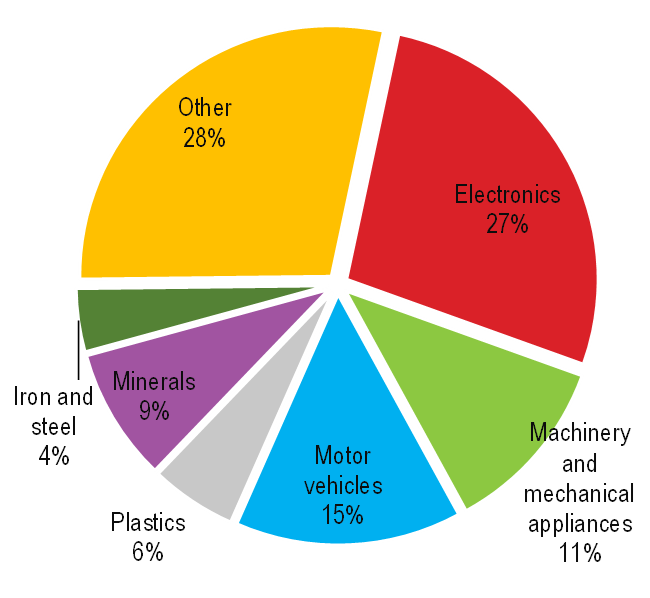

n 2023, Korea was the world’s fifth-largest car producer. Motor vehicles were Korea’s second-largest export, accounting for 15 percent of the total (Figure 3). The 25 percent tariff will disrupt globally integrated supply chains created over decades for just-in-time delivery and multi-region sourcing. Cars are the result of countless cross-border transactions. The average vehicle today contains more than 30,000 parts, about half of which are electronics. Consequently, the impact of the 25 percent tariff on cars will not be limited to car manufacturers.

Figure 3. Motor vehicles are the second-largest export category after electronics

Source: 2024 OECD Economic Survey of Korea

Concerns about the impact of higher tariffs are reflected in recent economic forecasts. The Bank of Korea, which last November had projected real GDP growth of 1.9 percent in 2025, revised its forecast in late February: “Economic growth is expected to slow down to 1.5 percent this year, falling significantly below the previous outlook, as both exports and domestic demand face increasing downward pressures due to the implementation of U.S. tariff policy and heightened domestic political uncertainty.” The OECD also cut its outlook for Korea’s annual growth to 1.5 percent in its March Interim Economic Outlook. The impact of U.S. trade policy is also reflected in the nearly 13 percent drop in Hyundai Motor’s stock price during the week following President Trump’s announcement of the 25 percent tariff on March 26. This was the main driver of the 5.2 percent decline in the KOSPI index during that period.

After Minister of Trade, Industry and Energy Ahn Duk-geun met with car manufacturers the day after the tariff announcement, he stated that Korean “automotive companies are expected to experience considerable difficulties in exports.” On April 6, the government announced a KRW 3 trillion (about USD 2 billion) aid package for the auto sector.

The United States also slapped tariffs on car exports from Japan. Japanese Prime Minister Shigeru Ishiba told the Diet in late March that these tariffs would have “an extremely large impact” on Japan’s economy. This grim assessment was backed up by the Bank of Japan Tankan Survey, which found large manufacturing firms’ business sentiment fell to a one-year low in the first quarter of 2025.

In response, Korea, Japan, and China held their first economic dialogue in five years on March 30 in an effort to promote regional trade and agreed on a “smooth and effective implementation” of the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP). The three countries also signaled interest in restarting talks on a free trade agreement, progress on which has been mostly stalled for over a decade.

Reciprocity and U.S. Trade

The new 10 percent tariff President Trump announced on April 2 does not cover certain key sectors such as energy, semiconductors, and pharmaceuticals. However, the administration said that tariffs on these sectors will be added later. The same day, President Trump announced that around sixty countries, including Korea, which the Trump administration describes as the “worst offenders,” are subject to reciprocal tariffs ranging from 10 to 50 percent (see Table 1 below). The United States Trade Representative defines reciprocal tariffs as the “tariff rate necessary to balance bilateral trade deficits between the U.S. and each of our trading partners.” It is based on a simple calculation: the U.S. trade deficit in goods with a particular country divided by the total goods imports from that country and then divided by two.

This calculation results in a U.S. tariff of 26 percent on Korean imports, surpassing the rates set on the European Union (20 percent) and Japan (20 percent) but below some other Asian countries, notably China (34 percent) and Vietnam (46 percent). However, the high tariffs imposed on Vietnam will negatively affect Korea, the largest foreign investor in Vietnam.

Table 1. Reciprocal tariff rates imposed by the United States on its trading partners

| Country | New tariff (%) | Share of U.S. imports (%) | Goods trade balance

(USD billion) |

| European Union | 20 | 18.5 | -241 |

| China | 34 | 13.4 | -292 |

| Japan | 24 | 4.5 | -69 |

| Vietnam | 46 | 4.2 | -123 |

| Korea | 26 | 4.0 | -66 |

| Taiwan | 32 | 3.6 | -74 |

| India | 27 | 2.7 | -46 |

| Switzerland | 32 | 1.9 | -39 |

| Thailand | 37 | 1.9 | -46 |

| Malaysia | 24 | 1.6 | -25 |

Source: Trump Tariffs Live Updates: Global Markets Reel From Shock of Tariffs – The New York Times.

President Trump announced on April 8 that he would pause the reciprocal tariffs on all countries except China, leading to a sharp rebound in stock markets around the world. The delay gives countries time to negotiate deals to reduce tariffs. Korea sent its trade minister, Cheong In-kyo, to Washington in early April to begin discussions with the Trump administration.

Randall S. Jones is Distinguished Fellow at the Korea Economic Institute of America. The views expressed here are the author’s alone.

Photo from Shutterstock.

KEI is registered under the FARA as an agent of the Korea Institute for International Economic Policy, a public corporation established by the government of the Republic of Korea. Additional information is available at the Department of Justice, Washington, D.C.