The Peninsula

The China-Russia Security Council Resolution Part 1: Sanctions Relief

By Stephan Haggard and Liuya Zhang

As 2020 gets underway, it is hard to avoid the obvious: diplomacy surrounding the Korean peninsula is stuck. The core question that divides the parties is—as it has long been—a tactical one. Are North Korea and the United States willing to trade incremental moves on the nuclear issue for partial sanctions relief?

The answer to this question rests largely on choices in Pyongyang and Washington. But for the first time since the collapse of the Six Party Talks, we have a document that outlines the Chinese and Russian positions in fairly granular detail: the draft UN Security Council resolution from the two countries that was leaked to CBS News in mid-December. It is worth a closer look not because it will go anywhere; the U.S. quickly shot it down. But it suggests limits to Beijing’s tolerance for the maximum pressure campaign and offers up an alternative, or at least complementary, diplomatic approach. A key element of that approach: it would give the Moon administration more leeway; indeed, President Moon signaled early that he supported the initiative and even dispatched a high-ranking aid to make the case to Security Council members.

We analyze the draft resolution in two steps, first looking at its economic provisions and then more closely at possible Chinese motives.

The preamble puts an overly-rosy light on a bad situation by welcoming the U.S. willingness to talk, North Korean restraint with respect to nuclear and missile testing and American restraint with respect to exercises. But buried in the preamble is also the strange claim—periodically revisited by Beijing–that UN Security Council resolutions were not intended to have “adverse humanitarian consequences for the civilian population.” A concern with adverse humanitarian effects is warranted; the National Committee on North Korea has long monitored potential adverse effects of sanctions on humanitarian operations in the country. But given that targeting sanctions solely on the leadership is effectively impossible, it is not clear how sanctions would work were the Chinese injunction given a broad interpretation.

Nonetheless, this claim sets the stage for the substantive proposal that UNSC sanctions be partially rolled back. The operational component of the resolution is dedicated to a series of measures that could be undertaken “in light of the DPRK’s compliance with relevant UN Security Council resolutions.” The menu includes:

- Granting the Moon Jae-in administration more leeway with respect to the inter-Korean rail and road projects, presumably by allowing South Korea to conduct a more extensive survey than the one conducted in late-2018 (our colleagues at Beyond Parallel have the best review of the technical issues);

- Outlining in detail—at the four-digit HS code level—a series of industrial goods that should be granted exemptions from export controls, ranging from nails and needles, to appliances, to wider categories such as agricultural machinery and “automatic data processing machines and units thereof, such as panel computers and micro computers” (HS 8471).

- Increasing humanitarian assistance to the DPRK and making it easier to secure humanitarian exemptions.

- And finally, tucked away in operative paragraph 8, reference to particular provisions of four prior Security Council resolutions in which China finally agreed to the sanctioning of North Korea’s commercial exports. Interestingly, the products in question are not mentioned directly, but by reference to the relevant resolutions and their operative paragraphs. But the measures include lifting sanctions against statues (UNSC 2321 para. 29); seafood (2371, para. 9); textiles (2375, para. 16) and labor exports (2375 para. 17 and 2397 para. 8).

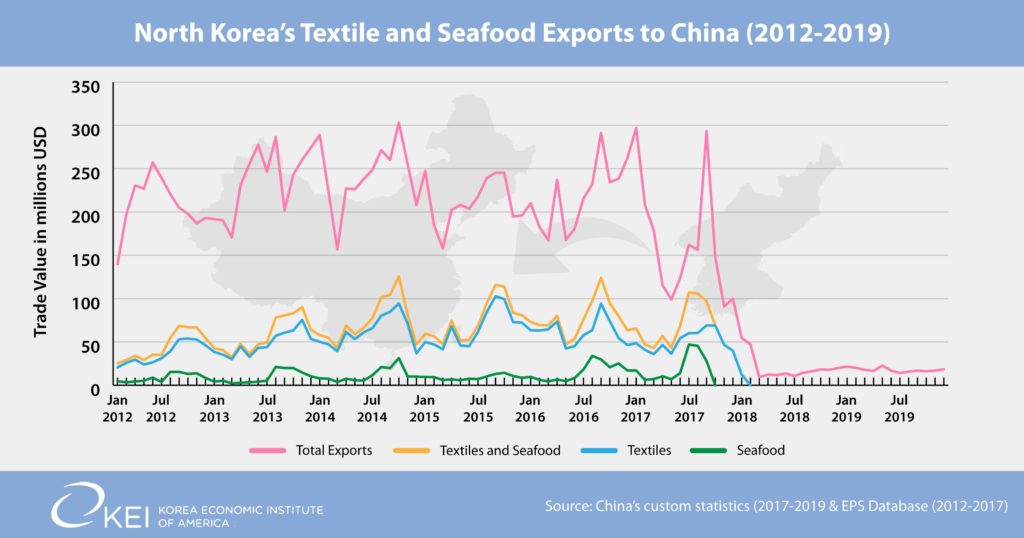

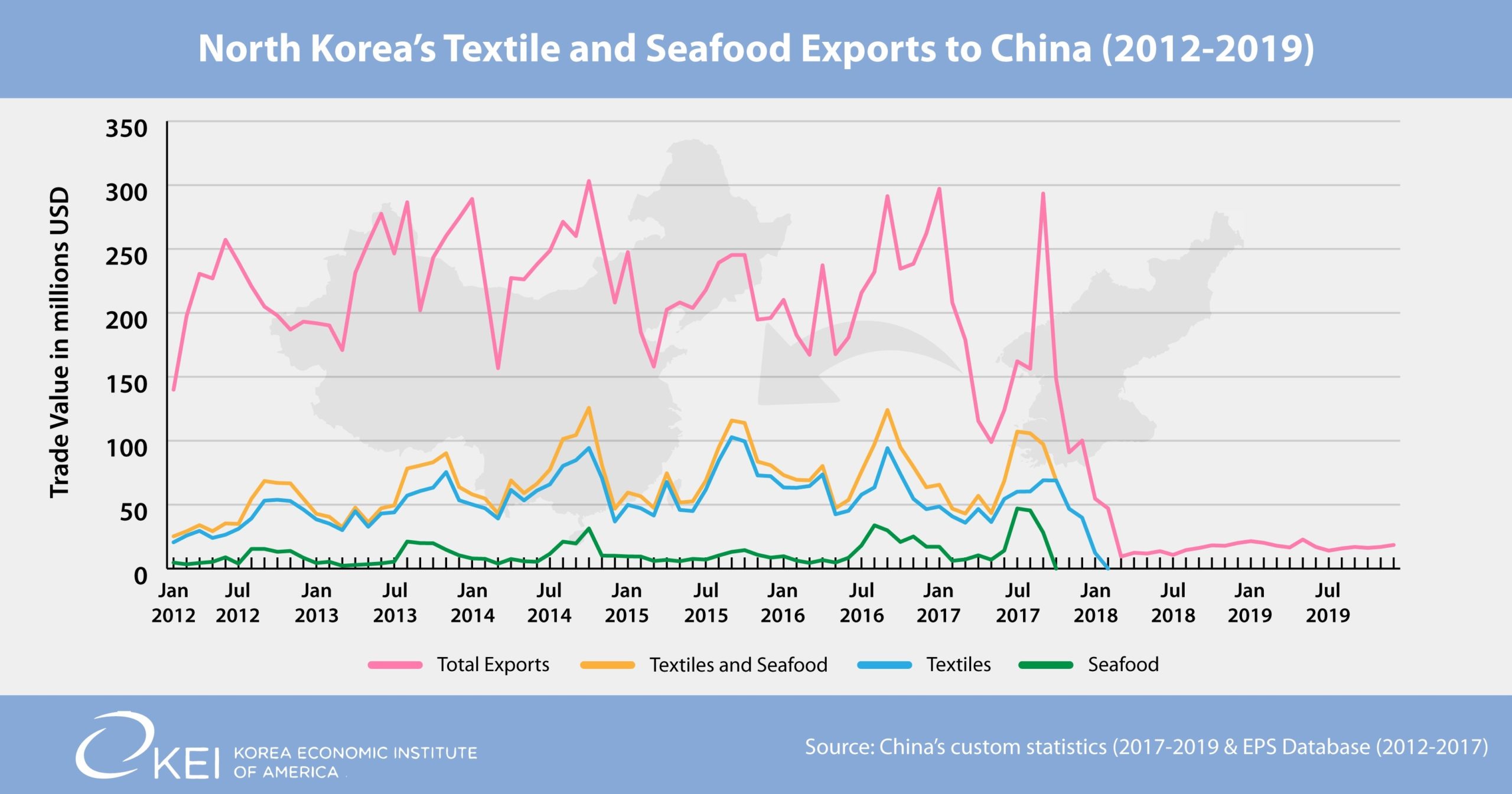

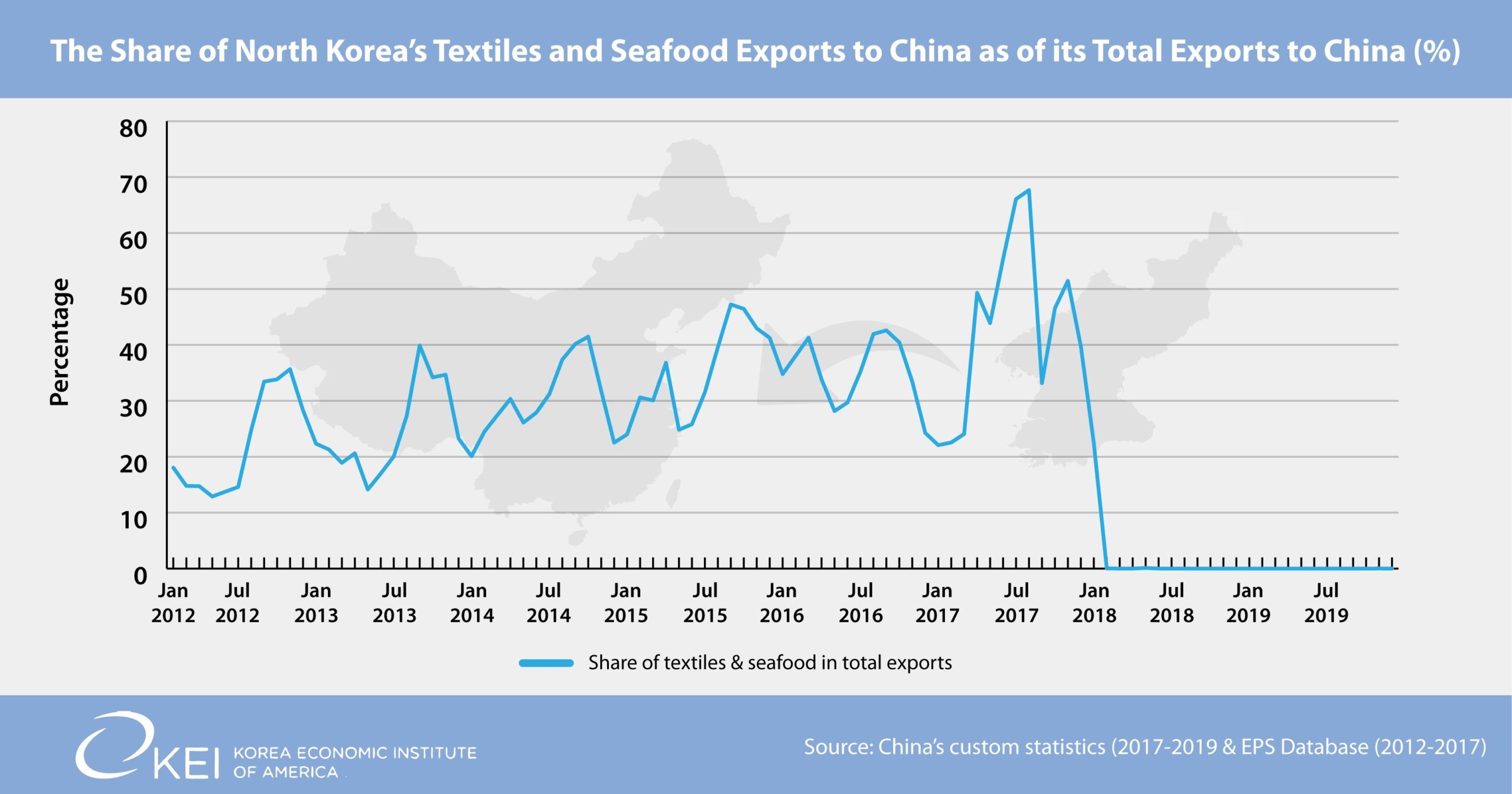

It was this last set of proposals that caught our attention, as sanctions against marine products, textiles and apparel constituted important hits to the ability of DPRK to earn foreign exchange. How much, exactly? The two figures below suggest the magnitude of the Chinese proposal. The first figure shows textile and seafood exports in dollar terms against total exports from 2012 through 2019; the second shows the share of those products in total exports for the same period. As can be seen, measures against these sectors—in conjunction with those against mineral exports—led to a virtual shutdown in North Korean exports to China in early 2018 (if the data are to be believed; we return to that issue below).

But what is interesting is the nature of the trade in these goods prior to that point. As can be seen, these two main product categories are trending up toward about 50% of total exports at the time they were shut down.

In the next post, we look at other economic measures that are afoot to support North Korea and possible Chinese motives for the initiative.

Stephan Haggard is a Non-Resident Fellow at the Korea Economic Institute and the Lawrence and Sallye Krause Professor of Korea-Pacific Studies, Director of the Korea-Pacific Program and distinguished professor of political science at the School of Global Policy and Strategy University of California San Diego. Liuya Zhang is a master student at the School of Global Policy and Strategy, University of California, San Diego. She received her Bachelor Degree of Arts from Fudan University and Master’s degree of International Studies from Seoul National University. The views expressed here are the authors’ alone.

Photo from Wikimedia Commons.