The Peninsula

The Beef with Tariffs (II): A Closer Look at Deficit-Driven Tariffs

Published April 8, 2025

Category: The United States

The first blog post of this series for the Korea Economic Institute of America (KEI) assessed the propriety of the White House’s estimate of South Korean tariffs on U.S. goods and its imposition of reciprocal tariffs at 25 percent. There are several ways that the Donald Trump administration could have derived the number, but it became clear by April 3 that the U.S. Trade Representative’s (USTR) calculation assumed that tariffs were linked with the U.S. trade balance by conceptualizing reciprocal tariffs as “the tariff rates that would drive bilateral trade deficits to zero.”

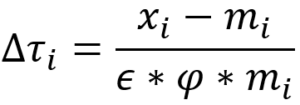

The method included parameters that accounted for the sensitivity of demand due to changes in import prices and the effect that tariffs have on domestic prices of imported goods. The model assumes no impact on exchange rates. The formula shows tariffs charged to the United States as:

where Δτ i is the tariff rate of country i;

ε is the elasticity of import demand with respect to price;

φ is the effect of tariffs on the price of imports;

xi is exports of country I;

and mi is imports of country i.

Estimating the value of ε and φ is a complex and time-consuming endeavor, given the sheer number of items to consider. The Harmonized System (HS) nomenclature has approximately 5,000 commodity groups identified by six-digit codes. Instead of estimating these two parameters, the USTR set the ε value at 4 and the φ value at 0.25. One assessment notes that the above model erroneously cites research showing estimates for φ to be 0.95 rather than 0.25. Considering that countries export different baskets of goods to the United States, assuming a constant ε value across all trading partners is an oversimplification. In other words, the ε and φ in the above equation equal one, creating a simple ratio of the U.S. trade deficit and imports by trading partners from the United States. The U.S. discounted reciprocal tariffs are then Δτ i divided by two.

Figure 1. Tariffs Charged by the United States and Trade Partners

Note: 2022 data on weighted average tariffs for Taiwan, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, the United Arab Emirates, Honduras, Tunisia, Serbia, Egypt, Saudi Arabia, Laos, and Morocco were missing, so they are excluded from the figure.

How does the tariff formula and its conclusion fare against World Bank data on tariffs levied by U.S. trade partners? Figure 1 depicts a scatterplot with a 45-degree line representing reciprocal tariffs, in which the tariff imposed by the United States (Y-axis) equals the weighted average tariff by trade partners (X-axis). Tariffs from the Trump administration are all above the line, indicating they exceed those imposed by respective trading partners.

Without exception, the April 2 tariffs are much larger than the tariffs levied on the United States, according to the most recently available data. Even when considering φ to be 0.95, most tariffs were effectively lowered to the universal tariff level of 10 percent but remained above levels considered strictly reciprocal.

To get a better sense of the variation in the magnitude of the tariff imbalance, one can take the difference between the Trump administration’s reciprocal tariff for a given country and the tariff rate levied on U.S. exports by the country. Figure 2 below depicts the order of the residual tariffs in these rates, which shows Vietnam is the highest on the list in terms of the difference between the United States’ imposed tariffs and its tariffs on the United States. For the Netherlands, the weighted average tariff on imports from the United States was 1.23 percent in 2022. The Netherlands is a member of the European Union, so it will face 20 percent tariffs despite reporting a USD 55.5 billion trade deficit with the United States in 2024.

Several developing countries face high tariffs. For example, Botswana, whose exports to the United States are almost exclusively diamonds, will face 37 percent reciprocal tariffs while effectively only imposing 2.03 percent tariffs on imports of U.S. goods.

South Korea (at 25 percent) sits right in the middle—it is in a tougher spot than the United Kingdom and Singapore but has it easier than China and Myanmar.

Figure 2. Difference Between Tariffs Charged by the United States and Trade Partners

Robert Lighthizer, the USTR during Trump’s first term, has echoed the view that fair trade relies on trade balance. This is consistent with the assumption underlying the USTR’s tariff calculations but contrasts with so-called strict reciprocity in trade. Because many of the announced tariffs far exceed those of the respective trade partners, nations now face the choice of retaliating and increasing tariffs against the United States.

This paper is the second in an ongoing series from KEI covering the impact of U.S. government tariffs on South Korean trade. You can read the first issue in this series by clicking here.

Nils Wollesen Osterberg is Economic Policy Associate at the Korea Economic Institute of America (KEI). Dr. Je Heon (James) Kim is the Director of Public Opinion and External Relations at KEI. The views expressed here are the authors’ alone.

Photo from The White House Flickr Account.

KEI is registered under the FARA as an agent of the Korea Institute for International Economic Policy, a public corporation established by the government of the Republic of Korea. Additional information is available at the Department of Justice, Washington, D.C.