The Peninsula

Survival Shows Redefine the K-Pop Industry

Published April 3, 2019

Category: Culture, South Korea

By Steven Lim

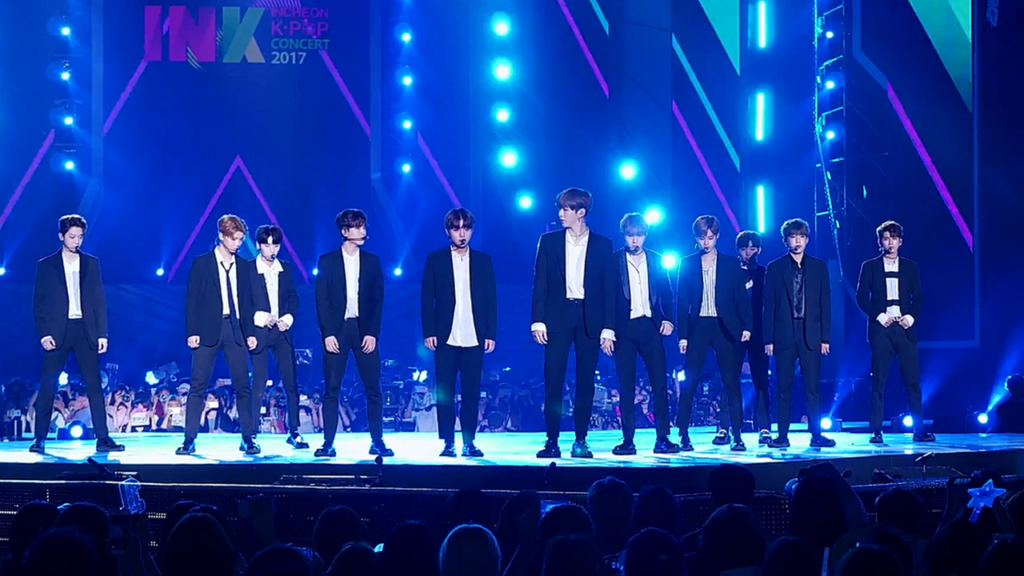

By integrating elements of a reality show and a traditional music competition, the TV program Produce 101 has generated greater public interest in K-pop from both Korean and international audiences.

Trainees from various entertainment companies exhibit their skills to join a new music group. The show is notable for not having any judges; viewers at home and in the studio exercise total control over the contestants through weekly votes. The final 11 or 12 contestants debut in a group together, signing a short contract.

The show’s three seasons have introduced new stars and increased K-Pop’s global reach in addition to exporting Korean TV programming. Simultaneously, the scope of the contestant pool – an inherent facet of the program – may hold back the K-pop industry from growing.

Pros

The Produce franchise is notable for its seamless expansion to other markets. Produce 48 localized the show for the Japanese audience by including contestants from the country’s flagship idol group AKB48. This generated significant interest in Japan. Additionally, watching the contestants work together to navigate the culture shock and overcome the language barrier contributed to growing the show’s audience beyond K-pop fans.

While voting was limited to Korea, the show’s simultaneous TV broadcast in Korea and Japan enabled Japanese viewers to actively follow the contestants. This helped the winning group, IZ*ONE, build a significant fan base in Japan, priming them for success there.

Moreover, IZ*ONE’s dual nationality helped them grow their presence in Japan. While many K-pop groups have Japanese members, IZ*ONE incorporated already-debuted Japanese idols to instantly boost their public recognition. Their hybrid Korean-Japanese management also provided them with opportunities in Japan that few K-Pop groups ever acquire. Through this collaboration, IZ*ONE’s debuts broke records in both countries, an incredibly impressive feat.

Similarly, the Produce series is helping export the Korean idol model to China in collaboration with Tencent. An official Thai version was called off last August, but a local version came out in February. The quick international adoption speaks to not only K-Pop’s popularity but also the Produce franchise’s brand strength abroad.

Cons

While entertaining, the sheer volume of contestants on the show makes it difficult for contestants to properly showcase their talents. Equitable screen-time distribution for a pool of 101 talents is nearly impossible, so accusations of favoritism have become a regular issue. Genuinely talented artists are susceptible to falling through the cracks.

The franchise may also inhibit substantive, long-term growth for K-Pop. Because the vast majority of contestants are signed with various agencies, they cannot stay as a part of the group formed by the program for very long. The winning groups’ contracts were/are 9 months, 1.5 years, and 2.5 years. Despite the show creators’ ambition to create a “global K-Pop girl band,” the contracts represent a self-imposed limit. A shorter average group lifespan is the last thing K-Pop needs.

But to reverse the process, the Produce franchise would need to substantially change its format. Instead of drawing from a multitude of agencies, and thereby constraining the group and its growth potential, the program should emulate shows like American Idol and The Voice and predominantly rely on free agent trainees. That would enable the network to build an enduring group with global ambitions.

Implications for K-Pop

Produce’s TV network has recognized some of the show’s limitations and made changes, including the extensions of contracts to five years. This is a smart business decision and will enable the winning group to capitalize on their potentially immediate success. However, the change could adversely affect the talent agencies that contribute the contestants for the program. The pre-debut process is resource-intensive for these agencies and their return-on-investment is curtailed if they split revenue and production costs with the network for a longer time period. The extension to the contract, nonetheless, represents progress. It remains to be seen whether it will be sufficient and what unintended consequences it might have.

For much of this decade, K-Pop has been the face of Korean soft power on the world stage. Likewise, Produce 101 has been the face of K-Pop TV programming since its inception. It has developed a solid model for localization through its success in Japan, China, and elsewhere. At the same time, Produce 101 has caused a paradigm shift in K-Pop TV programming, with several other shows following in its footsteps. It may have also set some precedents that are counterproductive to the long-term success of the industry.

Steven Lim is currently an Intern at the Korea Economic Institute. The views expressed here are the author’s alone.

Photo from Wikipedia.