The Peninsula

Revisiting the Korean War Armistice

By Mark Tokola

In the wake of the April 2018 inter-Korean summit in Panmunjom and the June U.S.-North Korea summit in Singapore, there is renewed talk about whether it is time to announce an end to the Korean War by means of a peace declaration, peace regime, peace treaty, or by some other means. There is nothing to prevent either or both Koreas, the United States, and/or China from declaring peace on the peninsula, but formally resolving the July 27, 1953 Armistice raises complex legal and political questions. It is worth revisiting the history and current status of the Armistice.

Conventionally, the purpose of any armistice is for the military commanders who are at war to sign an agreement to end hostilities. The terms of armistices are negotiated to ensure that both sides have the confidence to lay down their weapons and to have a common understanding of the situation that will be left on the battlefield. The later, political resolution of the causes of conflicts, reparations, and assurances of future peace are left to diplomats.

The Napoleonic wars were ended by armistice, leaving the political settlement to the Congress of Vienna. In World War I, the November 11, 1918 armistice that ended the fighting was followed by the Paris Peace Conference. In the case of Korea, the 1953 armistice was followed by a peace conference in Geneva that lasted from April 26 to June 15, 1954. The conference ended in failure and was never resumed, leaving the Korean armistice in place for 65 years and counting.

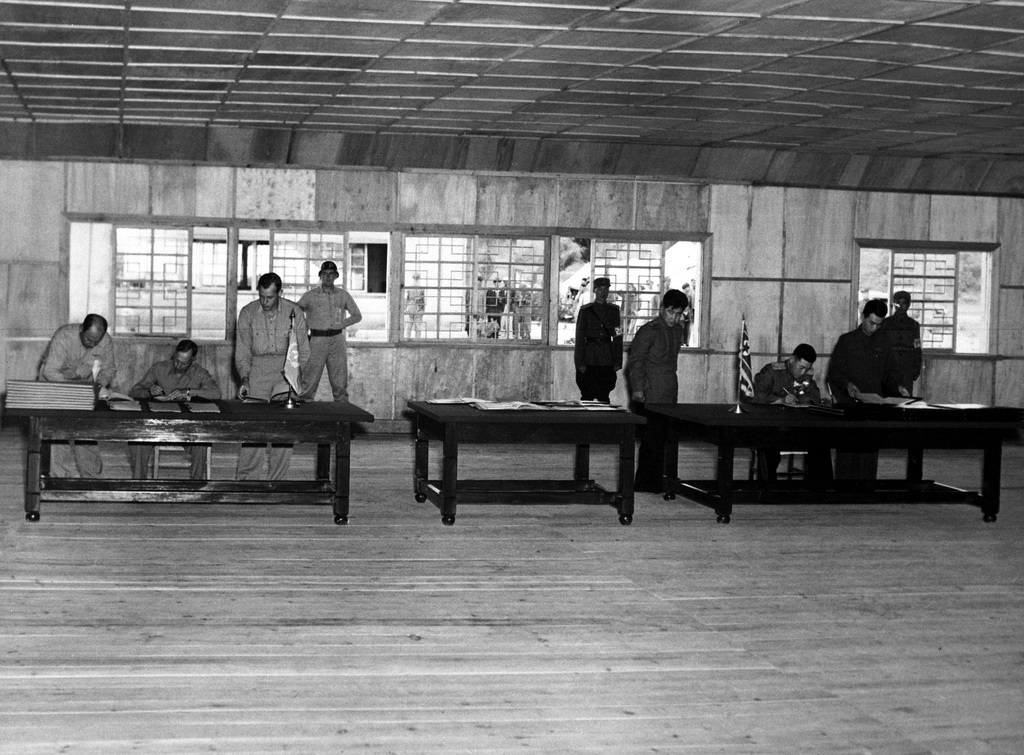

The 1953 Korean Armistice took the traditional form of being signed by military commanders rather than by politicians or diplomats. It bears two signatures, that of Lieutenant General William K. Harrison, Jr., who signed as “Senior Delegate, United Nations Command Delegation,” and that of General Nam Il as, “Korean People’s Army Senior Delegate, Delegation of the Korean People’s Army and the Chinese People’s Volunteers.” Exactly whom the two signers were representing is one of the questions regarding the armistice.

Most legal commentators agree that the United Nations Command (UNC) is not synonymous with the United Nations itself. This was made clear at the 1954 Geneva peace conference, in which on one side of the table were the countries which contributed forces to the UNC: the United States, South Korea, Australia, Belgium, Canada, Columbia, Denmark, Ethiopia, France, Greece, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Philippines, Thailand, Turkey and the United Kingdom. South Africa was a sending state, but did not attend the Geneva conference.

Under the terms of the peace conference, the sending states represented themselves separately. The United States, as Commander of the UNC, had a leading role but could not speak on behalf of the other UNC states without their permission. On the other side of the table were North Korea, the Soviet Union, and China.

China’s role in the armistice is ambiguous. On one hand, China denied official involvement in the Korean War, as seen by the Armistice being signed by a North Korean general on behalf of the Chinese People’s Volunteers. Even the nature of the Korean War itself was disputed. The UN characterized the conflict as a “collective action” to resist an “aggression.” North Korea, China, and the Soviet Union argued that it was a “civil war” in which no outside forces could legally intervene. The United Nations Security Council in 1951 identified China as an “aggressor” in the conflict, but the UNC treated the Soviet Union and China as neutrals to avoid broadening the conflict. China went on to undercut its own legal position by arguing at the United Nations that it had intervened in the conflict in right of self-defense.

The consensus among legal commentators is that China was indisputably a belligerent in the conflict regardless of the legal niceties of whether it was the Chinese People’s Army or Chinese People’s Volunteers who were involved. Therefore, China could have a role in ending the armistice, unless it chose not to have one. One of the issues raised in ending the armistice is that it may be awkward for China to have to revise its historic explanation of its role in the Korean War.

Regarding the current status of the Korean Armistice, there is little question that it is still in effect although North Korea has occasionally stated that it no longer felt bound by it. In 1996, the President of the United Nations Security Council made a statement endorsed by the full membership, including China and the United States, which said: “The Armistice Agreement shall remain in force until it is replaced by a new peace mechanism.” Note that the Security Council did not call for a “peace treaty”; the term “peace mechanism” is open-ended.

Resolving the armistice has been raised now and then. In 1994, North Korea called for talks between itself and the United States, insisting that the armistice could only be resolved by the two signatories — excluding South Korea and everyone else. In 1996, the United States and South Korea called for four-party talks to conclude the armistice: the U.S., South Korea, North Korea, and China.

Today, countries will do as they want regarding the Korean Armistice. There is no international tribunal that would judge whether the armistice was ended following proper procedures. However, in the interest of long-term stability on the peninsula, it would seem worth the effort to keep in mind the role of the United Nations and the United Nations Command sending states at the 1954 Geneva Peace Conference and in the years since. The long series of United Nations Security Council Resolutions regarding the peninsula should be concluded by a United Nations decision. South Korea, North Korea, China, Russia, and the UNC sending states should be parties to a settlement on the peninsula. A war that began and was fought on ambiguous terms should not also end ambiguously.

Mark Tokola is the Vice President of the Korea Economic Institute of America. The views expressed here are his own.

Photo from Morning Calm Weekly Newspaper Installation Management Command, U.S. Army’s photostream on flickr Creative Commons.