The Peninsula

Redrawing America’s Security Bargains in Northeast Asia

The stability of Northeast Asia has long rested on two strategic bargains with South Korea and Japan, forged out of the Korean War and formalized in security treaties. South Korea was compelled to accept the de facto division of the country in exchange for a treaty commitment, manifested in continuous U.S. ground forces, to defend against any North Korean threat of attack. With Japan, the bargain was different. The security pact provided a broad U.S. security umbrella, allowing Japan to focus on its economic recovery. In exchange, Japan provided bases and infrastructure that allowed U.S. air, naval, and marine infantry forces to project power regionally and globally. Both bargains depended on extended deterrence, or the credible threat that the United States would use force, including nuclear weapons if necessary, to protect its allies. That commitment also reduced incentives for South Korea and Japan to develop their own nuclear arsenals.

U.S. National Security and Defense Strategies

Donald Trump’s White House believes in a very different version of these security bargains. This was laid out in two documents—the National Security Strategy (NSS), issued in late November, and the National Defense Strategy (NDS), issued in late January.

Taken collectively, the Trump administration’s policymakers envision a situation in Northeast Asia and the Western Pacific where South Korea has the principal, if not almost sole, responsibility for defense against a potential North Korean attack. U.S. forces are repurposed and perhaps redeployed with a regional mission, mainly aimed at China, with potential use in situations such as a Taiwan contingency. Both South Korea and Japan are pushed, in turn, to not only spend much more but also to focus their spending on building capacities to defend the First Island Chain rather than their own territories.

As this writer noted in an earlier commentary, the NSS contained no mention of the U.S. defense of Korea and Japan, nor of extended deterrence commitments. Instead, Washington says it “must urge these countries to increase defense spending, with a focus on the capabilities—including new capabilities—necessary to deter adversaries and protect the First Island Chain.”

Strikingly, the NSS did not reference the Korean Peninsula broadly and did not reaffirm the long-standing goal of North Korean denuclearization. There was also no mention of the new strategic alliance between North Korea and Russia, despite Russia’s potential to vastly improve North Korea’s weapons of mass destruction program. The document also dilutes the potential China threat, focusing primarily on economic terms.

The NDS largely follows that framework but offers at least some limited discussion of the security environment in Northeast Asia and the Western Pacific. China’s military buildup is less of a direct threat in the NDS’s language than a rising power that needs to be balanced by the United States and its allies. The goal is one of an offshore counterweight, one more appropriate to the reduced global role envisioned by the Trump administration. The document also acknowledges that North Korea poses “a direct military threat” to South Korea and Japan and that the former must stay vigilant against the threat of invasion. While there is a nod to North Korea’s nuclear capability, there is no mention of the role of the nearly 30,000 U.S. forces stationed in South Korea.

Instead, the NDS states South Korea “is capable of taking primary responsibility for deterring North Korea with critical but more limited U.S. support.” What that support may be is not spelled out, but both the NSS and NDS hint that this may include the removal of U.S. ground and air forces, or at least their redeployment elsewhere. “This shift in the balance of responsibility is consistent with America’s interest in updating U.S. force posture on the Korean Peninsula,” according to the NDS. Extended deterrence is totally absent, or even the clear commitment made in the security treaty to fully defend South Korea.

The Colby Speech

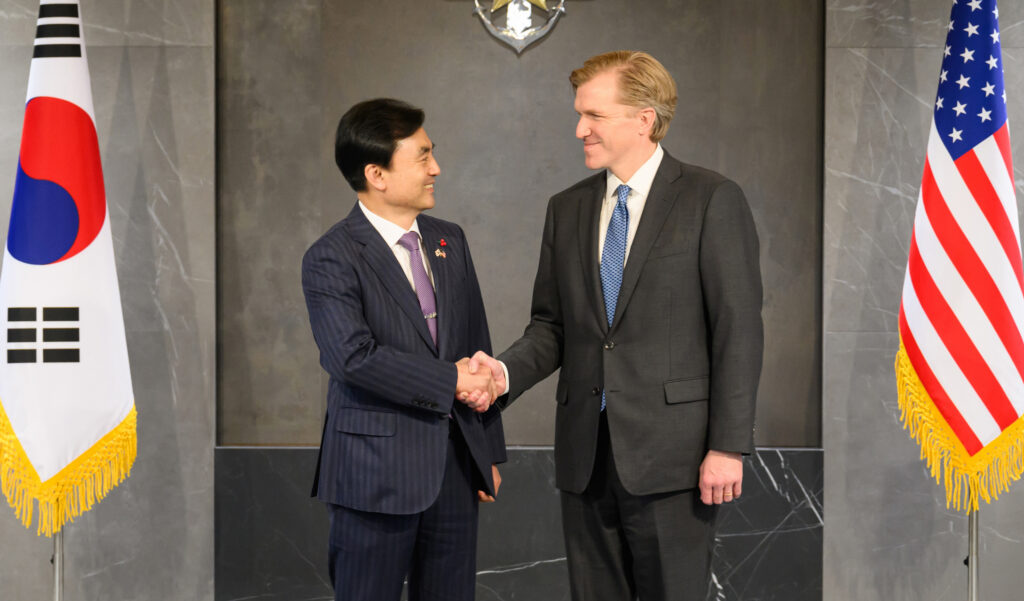

Under Secretary of Defense for Policy Elbridge Colby presented the implications of these policy statements more explicitly during recent visits to South Korea and Japan in late January. Colby stated the central purpose of U.S. national security policy in the Western Pacific as the search for a “stable balance of power” with China. To that end, Colby told an audience of elite Korean policymakers:

“We are focused on building a military posture in the Western Pacific that ensures that aggression along the first island chain is infeasible, that escalation unattractive, and war is indeed irrational. This includes a resilient, distributed, and modernized force posture” across the region.

Colby praised South Korea’s defense spending, calling the country a “model ally.” But in what may be considered a stunning omission for any senior U.S. defense official visiting Seoul, there was not a single word devoted to North Korea, its nuclear and missile buildup, its military axis with Moscow, or the United States’ seventy-three-year-long commitment to defend against it.

This was not lost on the audience. “In an 18-minute address, Colby mentioned China seven times but did not refer to North Korea even once,” the major daily Chosun Ilbo wrote in its account. Colby, whom the South Korean media credited as leading the drafting of the NDS, which was issued just before his arrival, “made these points during meetings with senior South Korean government officials.”

The Pursuit of a Trump-Kim Summit

The White House directed Colby to omit North Korea from his public comments as part of an effort to convince North Korean leader Kim Jong Un to meet President Trump again, a source within the administration told this writer on condition of anonymity. Talk of a meeting, perhaps tied to Trump’s planned visit to China in April, has been widely circulating. “The White House is opening a line of communication to Kim,” the source said.

“Considering how the Trump administration has sent mixed signals on this from day one, it is not really that surprising,” says Clint Work, a Research Fellow at the National Defense University. “I read it similarly, as an effort to tamp down language so as to try and open an avenue to, at the very least, talk with Pyongyang,” Work told the author.

South Korean officials offered little in the way of public reaction to Colby’s message. One reason for this is that President Trump threatened higher tariffs on South Korea the same day that the message was delivered, ostensibly because the National Assembly is slow-walking approval of a trade deal made last year. The timing was so coincidental that it sparked speculation that the tariff move was meant to reinforce Colby’s defense message, but sources within the Trump administration deny that intent.

For its part, the Lee Jae Myung administration may see a U.S. retreat serving its own goals of greater defense autonomy and engagement with North Korea. The South Korean president recently called on the country to rid itself of a “submissive mentality” of being dependent on others. A less engaged United States may accelerate the timetable for South Korean forces to assume operational control on the peninsula, create space for South Korea to enrich nuclear fuel, and incentivize new kinds of defense partnerships, such as in nuclear submarine technology. Support for nuclear armament remains high across South Korea as well.

South Korean policymakers have long resisted the idea that U.S. forces in the country should have any role other than defending against North Korea, or be reduced. But there is more willingness, says Work, to acknowledge and grapple with the idea that U.S. forces may need the “strategic flexibility” to deploy outside the peninsula.

South Korea-based researchers articulated the long-standing counterpoints to such flexibility in a recent paper published at one of the nation’s foremost think tanks, the Asan Institute for Policy Studies. “South Korean administrations have resisted any changes to U.S. force posture on the Korean Peninsula, whether in terms of total size or operational focus,” argue Peter Lee and Esther Dunay. “This is due to the ongoing North Korean military and nuclear threat, fears of a potential entanglement in any Taiwan Strait conflict, and longstanding fears of alliance abandonment.”

On the surface, the U.S. alliances with South Korea and Japan remain intact and manageable. But beneath that appearance of solidarity, the Trump administration’s attempts to redraw the security bargains that have underlain stability and peace in Northeast Asia are creating growing tension and uncertainty.

“We’re burning a lot of bridges,” the administration source told this writer. “We’re stressing the relationships with our allies.”

Daniel C. Sneider is a Non-resident Distinguished Fellow at the Korea Economic Institute of America and a Lecturer in East Asian Studies at Stanford University. All views are the author’s alone.

Feature image from Under Secretary Elbridge Colby’s official X account.

KEI is registered under the FARA as an agent of the Korea Institute for International Economic Policy, a public corporation established by the government of the Republic of Korea. Additional information is available at the Department of Justice, Washington, D.C.