The Peninsula

Policies to Reverse the Decline in the Fertility Rate Part 2: Improving the Economic Prospects of Young People

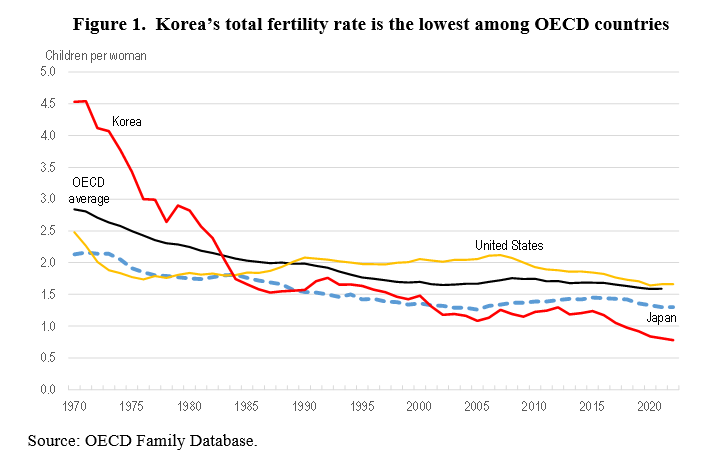

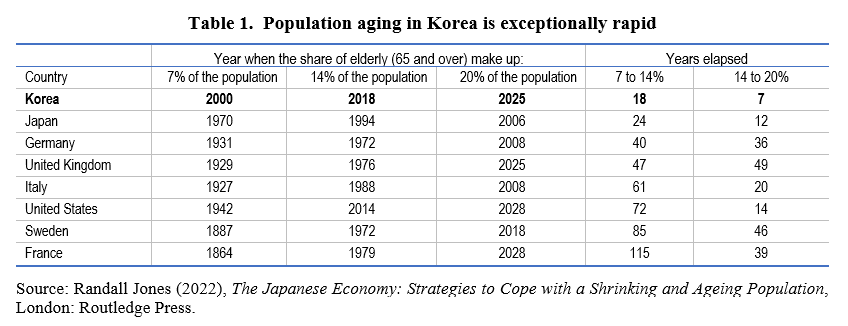

The drop in Korea’s total fertility rate to 0.78 in 2022 has heightened concerns about the impact of rapid population aging and decline. Despite numerous government initiatives, such as introducing free early childhood education and care in 2012, the fertility rate has continued to edge down. Korea’s median age jumped from 33.6 years in 2005 to 44.5 in 2023, and its total population declined in 2022 for the second straight year. Demographic change in Korea is exceptionally rapid compared to other advanced countries (Table 1).

There is no simple explanation or solution for the low birth rate – it is a combination of complex social issues. As in other countries, life goals other than family and children, such as career advancement, wealth and self-realization, have gained importance. The difficulty women face in combining employment and family responsibilities was identified as a key obstacle to having children in Part 1 of this note. Consequently, policies that make it easier for women to combine employment and family have resulted in a positive cross-country relationship between fertility and female employment. Policies promoting better work-life balance, such as shorter working hours, greater use of parental leave by fathers and a more equal division of unpaid labor (childcare, housework, etc.) by parents are associated with higher fertility. This note focuses on another critical issue – the uncertain economic prospects of young people that prompt them to delay or forgo marriage and children.

The trend toward later and fewer marriages

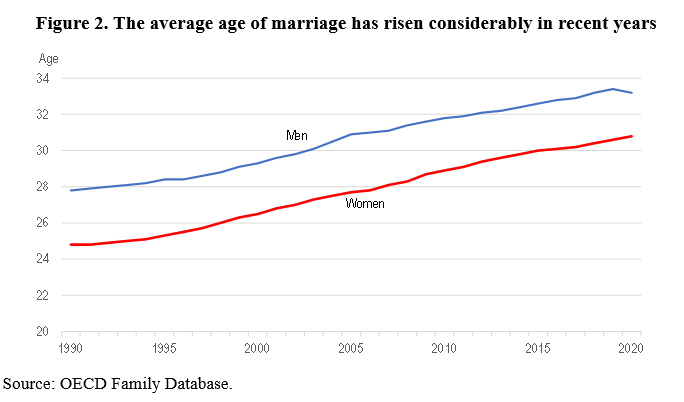

Given that 97.5% of births in Korea are to married couples, removing obstacles to marriage, particularly at a younger age, would boost the fertility rate. The marriage rate has fallen from 9.6 per 1,000 persons in 1990 to 4.2 in 2020, partly reflecting the smaller share of young people in the population. In 2020, 42% of Koreans in their 30s were single (51% of men and 34% of women).. Koreans who do marry wed at a later age. The average age of first marriage increased by 5.4 years for men and 6.0 years for women since 1990, reaching 33 and 31 years, respectively (Figure 2).

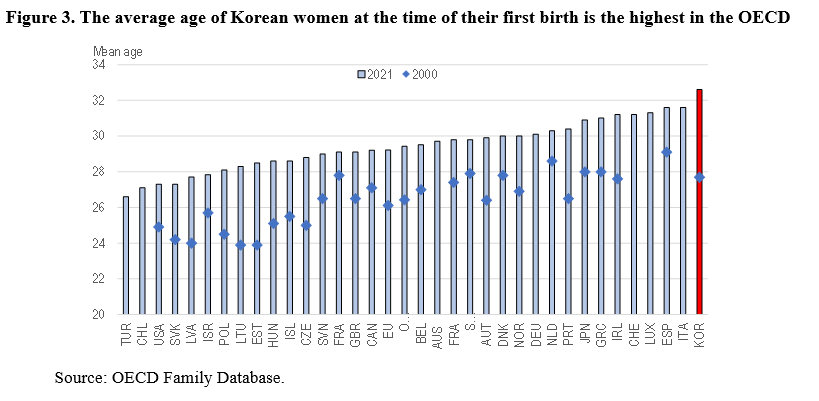

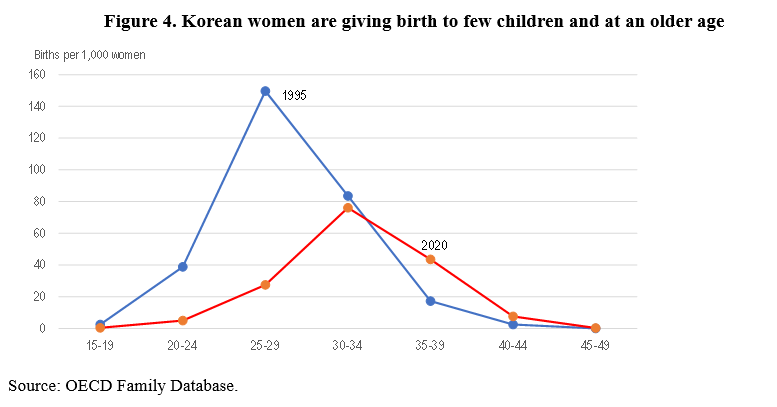

Later marriage has resulted in women bearing children at an older age. Since 2000, the average age of women at the time of their first birth rose by five years to 32.6 years in 2020, the highest among OECD countries (Figure 3). In 1995, half of the babies were born to women in the 25-29 age group. Women in the 30-34 age group bore half of the babies born in 2020, with the 35-39 age group accounting for another quarter (Figure 4). The trend to later marriage and childbearing means that an increasing share of couples will not be able to achieve their desired numbers of children due to problems with health and infertility. One out of 10 newborn babies in Korea in 2022 were conceived using infertility treatments. The Seoul metropolitan government recently announced that it will subsidize infertility treatments.

Economic challenges facing young people in Korea have contributed to the falling fertility rate

Korea’s younger generation is sometimes referred to as the “sampo generation” (literally, “giving up on three”) because they have abandoned dating, marriage and children. Young people face many challenges: intense competition to enter good universities in a society that prioritizes education; the high cost of tertiary education, as 77% of students attend private universities; and the lack of affordable housing in the Seoul metropolitan area, where about half of the country’s population lives. Nearly three-quarters of high school graduates advanced to college or university in 2021 and the proportion of the 25-34 age group with tertiary education is the highest among OECD countries (Jones and Lee, 2022).

The zeal for higher education is motivated by the hope of avoiding precarious and low-paid jobs in small companies and winning a “golden ticket” – employment in a large corporation or the public sector. Young people queue for such jobs, while small firms, which pay relatively low wages, face labor shortages. Wages paid by firms with at least 300 employees pay nearly twice as much as firms with ten or fewer workers. Consequently, only 4% of young people want to work in an SME, while nearly two-thirds hope to work at large firms, government agencies or public companies, according to a government survey.

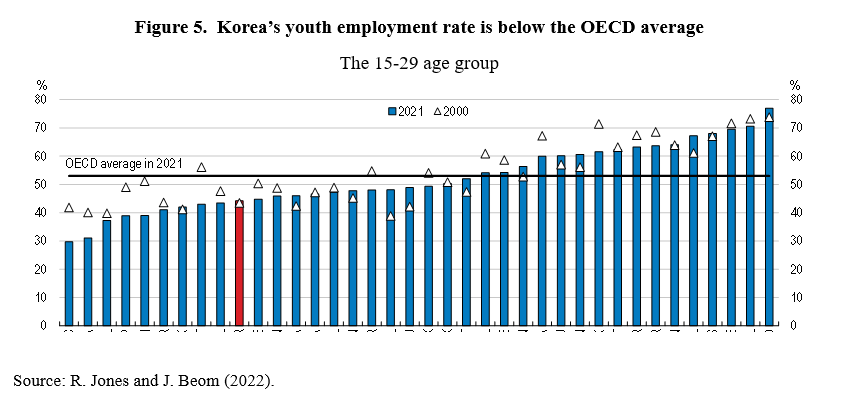

The mismatch between the labor market and the education system contributes to a low employment rate for young Koreans. The employment for the 15-29 age group in 2021 was 44%, well below the 53% OECD average (Figure 5). In addition, a high proportion of youth not are in the labor market. The share of youth aged 15 to 29 who are neither employed, nor engaged in formal education or training (the so-called NEETs) was 18.4% in 2017, the sixth highest among OECD countries. The NEET rate is exceptionally high among college and university graduates; 45% of NEETs in Korea have a tertiary degree compared to 18% in the OECD area. Education mismatches are driven in part by expectations mismatches. Young people who fail in their initial efforts to find a job often seek to improve their chances by pursuing additional formal and informal education, such as foreign language classes, rather than accepting a job below their expectations.

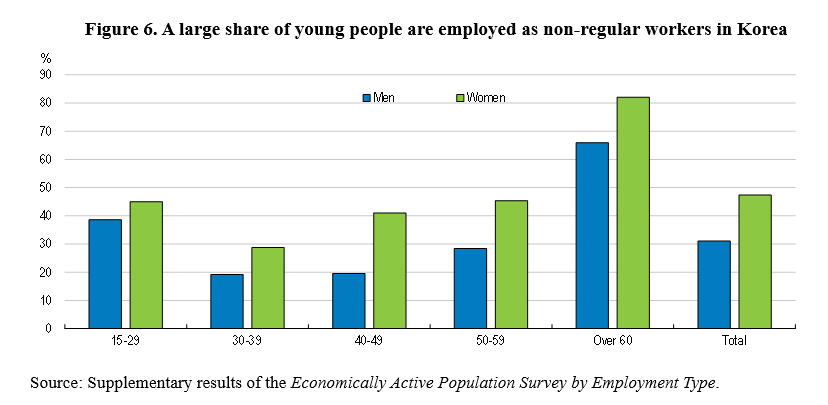

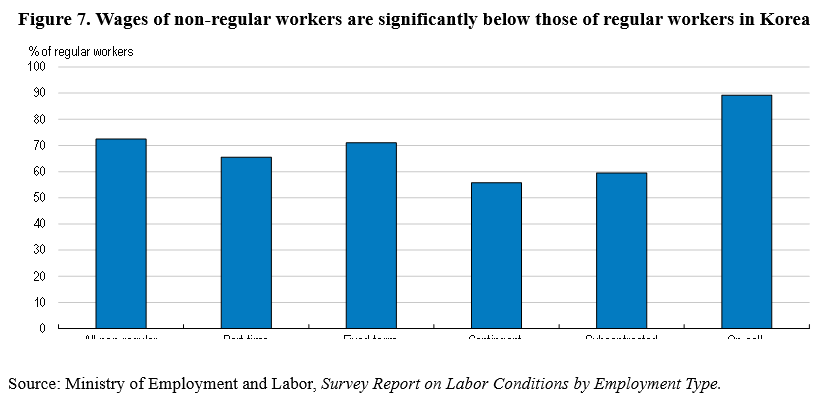

Many young people who are employed work in non-regular jobs in Korea’s dualistic labor market. In 2021, 45% of young female employees and 39% of young male employees were non-regular, the highest of any group except the elderly (Figure 6). Regular workers receive high wages and social insurance coverage and strong employment protection. Non-regular workers, which includes fixed-term, part-time and atypical workers, receive lower wages, are less likely to be enrolled in social insurance and work in precarious jobs. In 2020, the hourly wage of non-regular workers was 28% below that of regular workers (Figure 7). The earnings gap is even larger in practice, as 62% of regular workers received company bonus payments, which account for around a quarter of annual earnings, compared to 21% of non-regular workers. The proportion of non-regular workers enrolled in the National Pension System (62%), National Health Insurance (65%) and Employment Insurance (74%) in 2020 was well below the more than 90% for regular workers. Moreover, less than a quarter of non-regular workers were enrolled in company pension systems compared to 59% of regular workers.

Conclusion

Raising the fertility rate depends in part on improving the economic position of young people, which will require fundamental economic reforms. As stated in the report on the first meeting of the Youth Policy Coordination Committee in 2020, chaired by the Prime Minister, “It is difficult to expand youth employment and improve the quality of jobs due to changes in the industrial structure and the dualistic structure of the labor market such as regular jobs versus non-regular jobs and large enterprises versus small firms” (OGCP, 2020). Reforms to break down labor market dualism and reduce the wage and productivity gap between large and small firms are essential.

Randall S. Jones is a Non-Resident Distinguished Fellow at the Korea Economic Institute of America. The views expressed here are the author’s alone.

Photo from Hyunwoo Sun’s photostream on flickr Creative Commons.