The Peninsula

Korean Policies to Reverse the Decline in the Fertility Rate Part 1: Balancing Work and Family

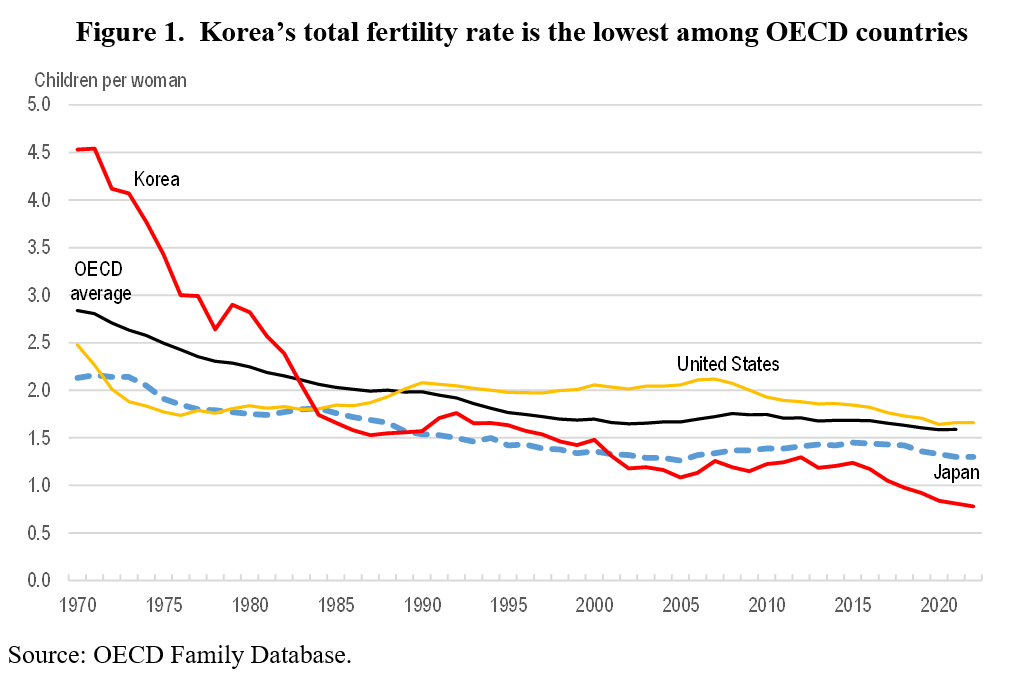

President Yoon Suk Yeol presided over the Presidential Committee on an Aging Society and Population Policy in March. It was the first time that a president had attended a meeting of the Committee since 2015, reflecting rising concern over the decline in Korea’s total fertility rate to 0.78 in 2022 (Figure 1). It is the lowest among OECD countries, though similar to the rate in some other Asian economies, such as Singapore (1.1), Taiwan (1.0) and Hong Kong (0.9). The number of babies born dipped to another new low in March 2023, falling 8.1% from a year ago, the 88th consecutive monthly decline. The number of births has remained below the number of deaths since 2020. President Yoon stated “We need to calmly re-evaluate the low birth rate policy and figure out why it failed based on scientific evidence.”

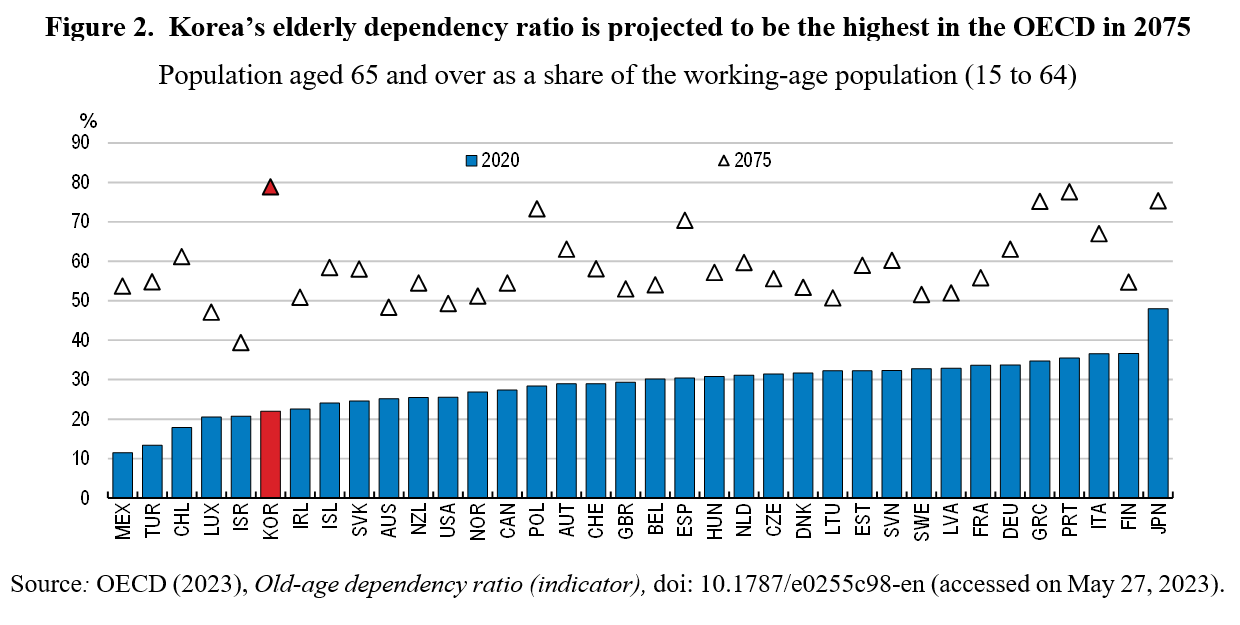

Under current trends, Korea’s elderly dependency ratio is projected to be the highest among OECD countries in 2075 at 79% (Figure 2). This implies that the number of working-age persons per elderly would drop from 4.5 in 2020 to less than 1.3 persons in 2075. The rapid pace of population aging would have significant economic, social and fiscal impacts, including a heavy burden to provide health and long-term care to older persons.

The government has spent more than KRW 280 trillion ($211 billion) since 2006 to raise the fertility rate. At the March meeting, the Committee criticized the Fourth Basic Plan for an Aging Society and Population Policy (2021-25) as “abstract and unclear.” Many of the 214 tasks, such as funds for industry-academia cooperation and cultivating new artists and cultural experts, appear unrelated to the fertility issue. The Committee is taking a “select and concentrate” strategy that focuses on policies most likely to have a direct impact while discarding other policies. It selected five key areas: i) balancing work and childcare; ii) childcare and education; iii) housing support; iv) child-rearing expenses; and v) health and happiness. The 2024 government budget will allocate KRW 39.8 trillion ( $30 billion) to encourage more births.

Improving the balance between work and family

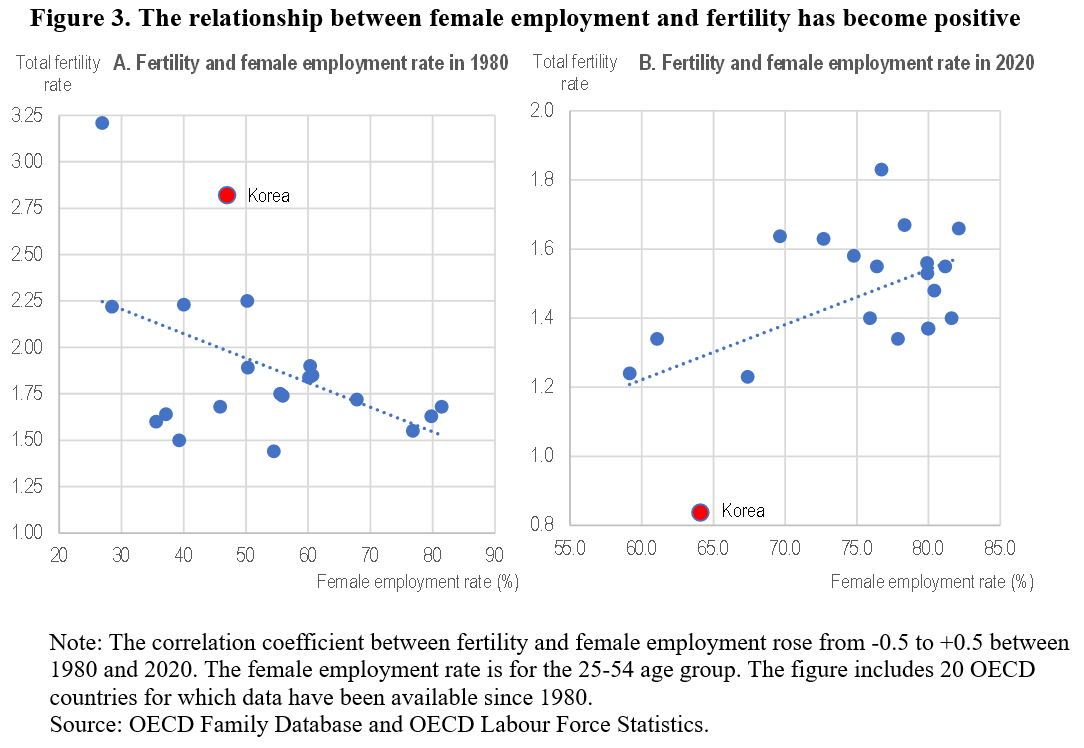

As women’s education, employment and wages increased, the opportunity cost of having children increased. The difficulty of balancing work and family commitments forced many women to choose between leaving their jobs to raise children or forgoing children to continue their careers. Consequently, the cross-country correlation between female employment and fertility was negative in 1980 (Figure 3, Panel A). However, in recent years, OECD countries with higher employment rates for women tend to have higher fertility rates. Consequently, policies that made it easier for women to combine employment and family have resulted in a positive relationship between fertility and female employment (Panel B).

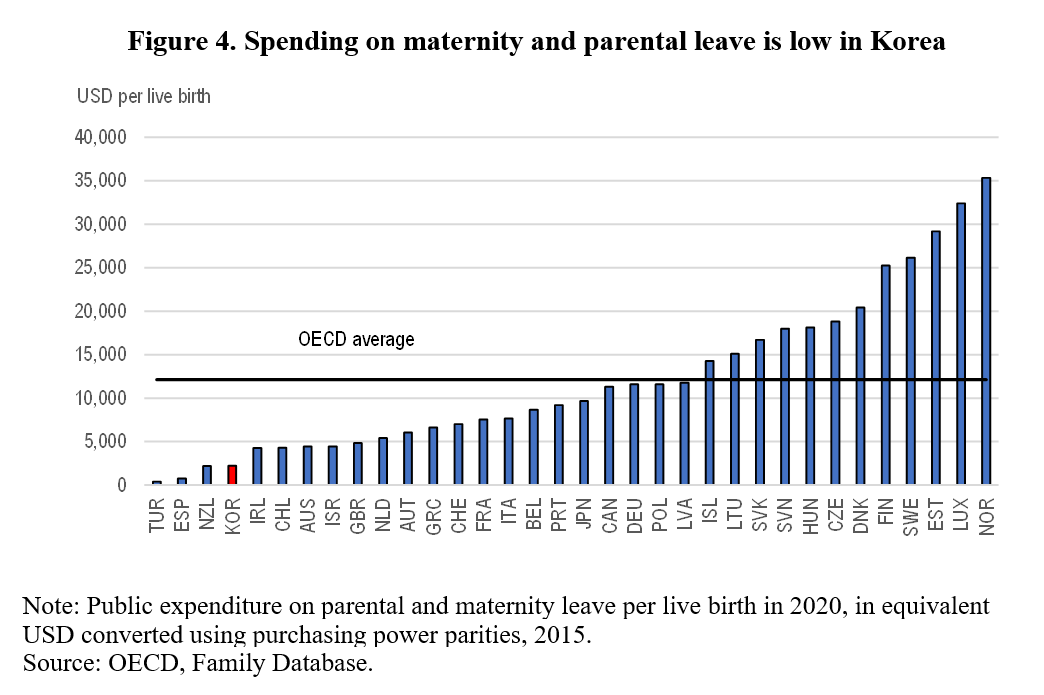

Policies to encourage parental leave have been found to have a positive association with total fertility rates. Parental leave in Korea is exceptionally generous, with one year available for both mothers and fathers, paid up to 80% of the average monthly wage. However, in 2020, only 63.9% of eligible mothers and 3.4% of eligible fathers took parental leave. This is low compared to Japan, where 81.6% of mothers and 12.7% of fathers took parental leave that year. Gender norms, a lack of enforcement of parental leave rights and the cost incurred by employers limits the take-up of parental leave by fathers. In addition, Korea’s work culture emphasizes long working hours and discourages absences, particularly by men . Consequently, public expenditure on parental and maternity leaves per live birth in Korea was less one-fifth of the OECD average in 2020 (Figure 4).

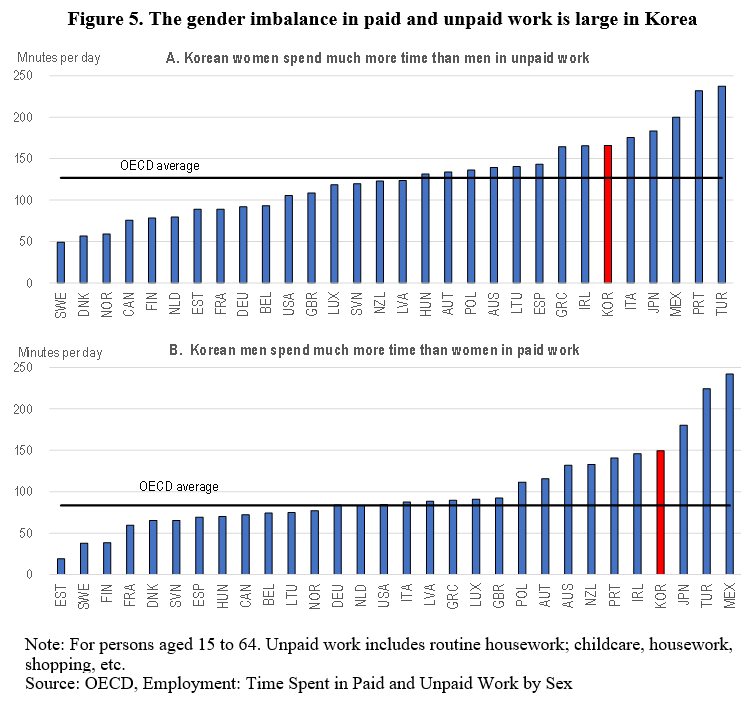

In addition, long working hours and low flexibility for parents make it difficult to combine work and family. In 2018, the limit on working time was cut from 68 to 52 hours per week in firms with 300 or more employees and this rule has been applied to all firms with five or more employees since 2021. Still, a 52-hour working week is incompatible with taking an active part in raising children and other domestic work. The time Korean men spend on paid labor is the fourth longest among OECD countries and 2½ hours longer per day than Korean women. Long work hours, long commutes and after-work socializing limit men’s availability for unpaid labor. With long working hours concentrated among men, women in Korea bear the brunt of unpaid labor – childcare, housework, shopping, etc. Men spend an average of 49 minutes a day on “unpaid labor” – about one-third of the OECD average, while women spend 3½ hours.

Consequently, women devote nearly three hours per day more to unpaid labor than men (Figure 5). In dual-income households, fathers tend to arrive home later than mothers. In sum, the gender gap in paid and unpaid work in Korea is exceptionally large, making marriage and children unattractive to some women.

Conclusion

The Presidential Committee on an Aging Society and Population Policy has correctly identified balancing work and childcare as a key to reversing the decline in the fertility rate. One key is to increase the take-up and duration of parental leave, particularly by fathers. Reducing the financial burden of parental leave on families and firms and requiring firms to disclose the percentage of their eligible male employees who take leave would increase the take-up of leave. However, the government’s plan to raise the limit on working hours from 52 hours per week to 69 hours may reduce work-life balance and make it more difficult for women to balance employment and family responsibilities. In any case, raising the fertility rate is a difficult challenge. As President Yoon stated, “Even if the low birth rate problem cannot be solved, I believe that it is the country’s basic duty to at least ensure that children born in Korea can grow up bright and healthy.”

Randall S. Jones is a Non-Resident Distinguished Fellow at the Korea Economic Institute of America. The views expressed here are the author’s alone.

Photo from watchsmart’s photostream on flickr Creative Commons.