The Peninsula

Korea’s Participation in RCEP is Likely to be Beneficial

On November 15th, fifteen countries signed the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), the world’s largest free trade agreement. It includes the ten ASEAN countries and some of their key trading partners – China, Japan, Korea, Australia and New Zealand. With a combined 2.2 billion people, the RCEP member countries account for about 30% of the world’s population and economic output.

RCEP, which was launched during the 2011 ASEAN Summit, is expected to eliminate about 90% of tariffs between member countries within 20 years and aims to establish standards for intellectual property rights and e-commerce. The RCEP does not aim at a dramatic liberalization of trade barriers, but will tie together existing trade agreements. ASEAN already has trade agreements with China, Japan, Korea, and Australia and New Zealand. Of the $2.3 trillion in goods traded between the RCEP countries in 2019, more than 80% was between countries already connected by a trade agreement. Indeed, seven RCEP member countries are already members of the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP), which took effect in 2018.

The RCEP is a slower and more incremental approach to trade liberalization compared to the high-level, detailed and ambitious CPTPP. Moreover, RCEP’s coverage of services and agriculture is limited and it does not include standards on labor, the environment and state-owned enterprises, as does the CPTPP. The difference between the two trade agreements reflects the fact that the CPTPP consists primarily of high-income countries, while the RCEP includes low-income countries, such as Laos and Myanmar.

The projected benefits from the RCEP

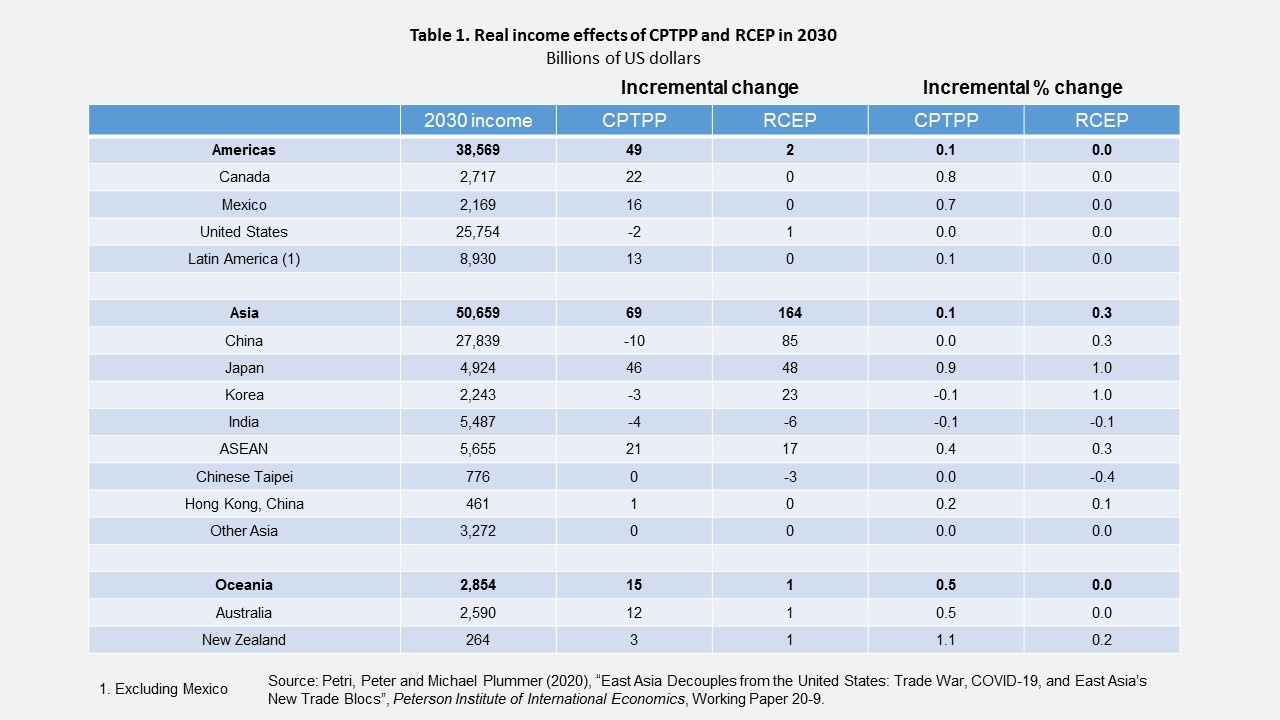

A recent study estimated that RCEP will boost global national incomes by $186 billion annually by 2030 by promoting trade in the Asia-Pacific region. Trade among RCEP countries is projected to rise by $428 billion, while trade among non-members falls by $48 billion. RCEP will reorient trade and economic ties away from global linkages toward regionally focused relationships in East Asia (Petri and Plummer, 2020). One important effect may be to strengthen the resilience of supply chains by supporting the development of new production bases that can withstand the sudden imposition of trade restrictions.

However, the same study projects that more than 90% of the benefits will accrue to China, Japan, and Korea, which account for about four-fifths of the total GDP of RCEP member countries (Table 1). Korea’s real income is expected to be 1% higher in 2030 than it would have been without the RCEP. The concentration of gains in the largest participating countries reflects the fact that RCEP is the first major trade agreement to include China, Japan and Korea. India, the third-largest Asian economy after China and Japan dropped out of the agreement at the last moment.

The large gains to Korea result from expanded trade with RCEP member countries, which already accounts for about half of its international trade. In particular, Korean firms expect to increase sales of car parts, steel and electronics following tariff reductions. Indonesia, the Philippines and Thailand will remove tariffs on car parts. Some countries will eliminate tariffs on steel and on electronic products, such as refrigerators, washing machines and air conditioners. The Korea Institute for International Economic Policy estimated that the reduction of tariffs as a result of the RCEP will boost Korea’s GDP by between 0.4% and 0.6%. In addition, RCEP will improve intellectual property rights compared to the 2007 FTA between ASEAN and Korea, which provided little protection for Korean companies. In contrast, the RCEP includes a total of 83 provisions covering such areas as trademarks, patents and designs.

The RCEP is the latest success of Korea’s FTA strategy

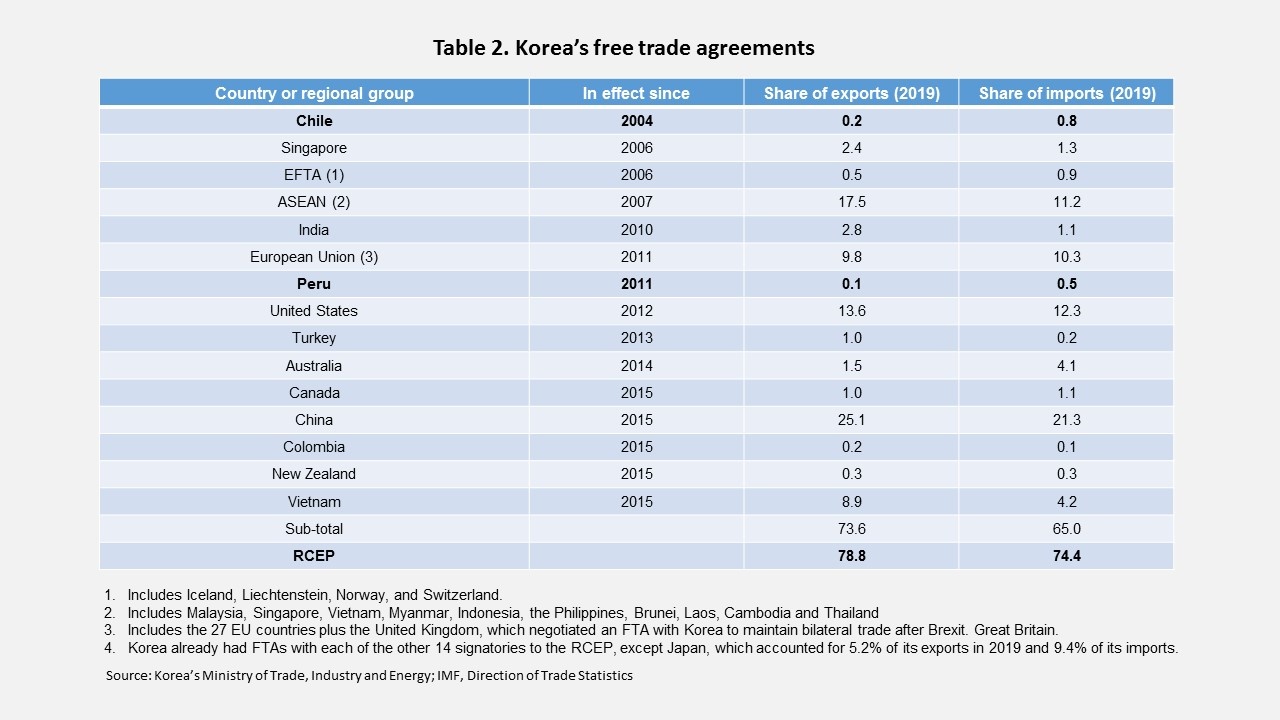

Korea was a latecomer to the wave of FTAs that started in the 1990s. It was not until 2004 that it entered its first FTA and it was with Chile, a relatively minor trading partner (Table 2). By 2015, though, Korea had a total of 15 agreements that covered 52 countries. Moreover, Korea is the only country to have FTAs with the United States, the European Union and China. In 2019, FTA partner countries accounted for 73.6% of Korea’s exports and 65.0% of its imports. In contrast, Japan’s FTAs cover only about a third of its exports, well below its objective of 70%.

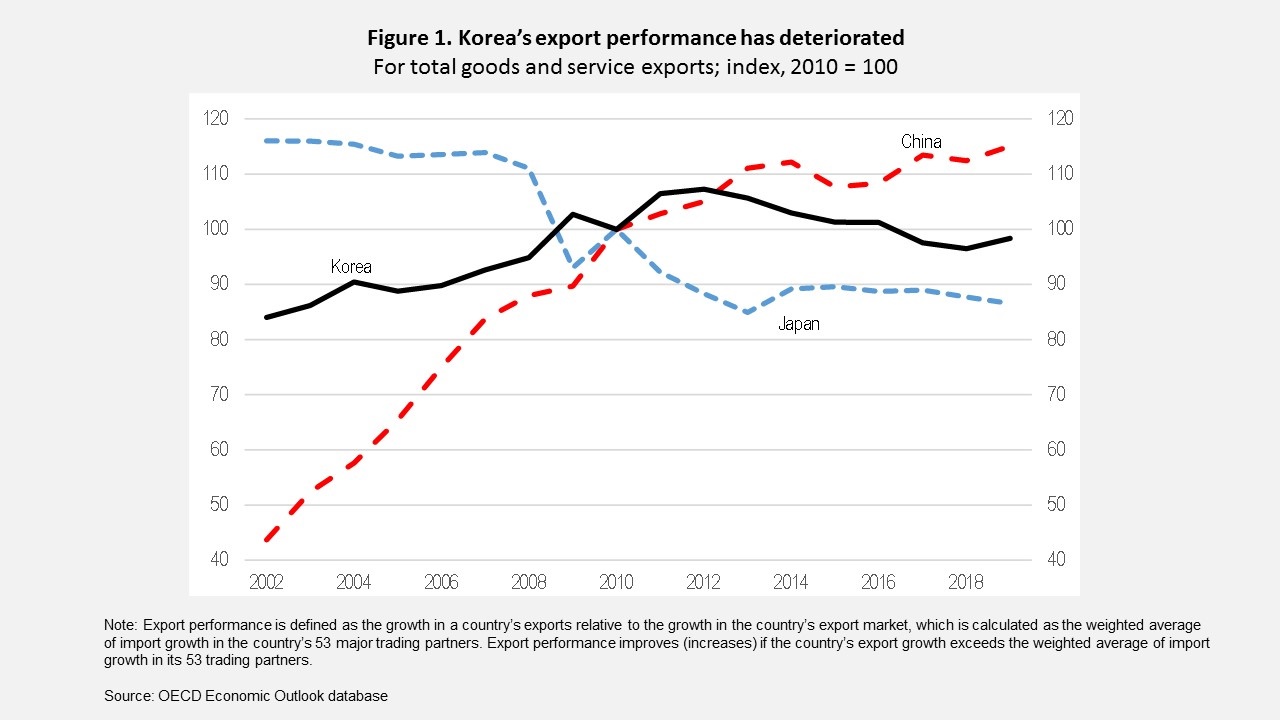

Exports, which account for nearly half of Korea’s GDP, are essential for economic growth. However, Korea’s export performance (the growth of export volume relative to the growth of imports in Korea’s trading partners) has deteriorated since its peak in 2012 (Figure 1). Meanwhile, China’s export performance has continued to improve, though at a slower pace since 2010 and Japan’s performance has stabilized after a long-term decline. The slowdown in Korea’s export growth – from an 11.4% annual rate over 2001-11 to 2.8% since 2011 – reflects in part the internationalization of Korea’s leading companies. For example, around 60% of Hyundai cars in 2019 were produced outside of Korea, contributing to the decline in Korea’s car exports from 3.0 million in 2012 to 2.4 million in 2019. The deterioration in Korea’s export performance underlines the importance of trade agreements. At a ceremony on December 8, 2020 to mark the 57th Trade Day, President Moon Jae-in said that the government will expand Korea’s free trade network to prepare the country for increasing competition.

Directions for Korea’s trade policy

All of the RCEP member countries, except Japan, already participate in FTAs with Korea. Joining the RCEP will thus increase the share of Korea’s exports going to FTA partners by 5.2 percentage points to 78.8% and imports by 9.4 points to 74.4% (Table 2). Given that the share of Korea’s trade covered by FTAs is already very high, the priority is to deepen existing agreements with key trade partners, notably China and Japan.

The impact of the 2015 Korea-China FTA appears limited, reflecting its “narrow coverage and tenuous commitments.” Moreover, it has not been followed by second-stage negotiations, as originally planned. Bilateral trade relations have been marred by Chinese retaliation against certain Korean companies (Lotte) and a few sectors (tourism and entertainment) following Seoul’s decision in 2016 to participate in the Terminal High Altitude Area Defense (THAAD) missile defense program.

As noted above, RCEP is unique as the first major trade agreement to link Korea, China and Japan, suggesting that it could accelerate progress towards an FTA among the three countries. Negotiations on such an agreement were launched at the same time as RCEP in 2012, leading to 16 rounds of negotiations. However, political disputes have hindered progress. Following the signing of RCEP, China has renewed its push for a Korea-China-Japan FTA. However, Japanese Prime Minister Suga refused to come to Seoul for a planned summit in December of the leaders of the three countries, citing the lack of progress in resolving the wartime forced labor issue with Korea. The disagreement led Japan to tighten export licensing rules in 2019 for its shipments of key inputs used in the manufacture of semiconductors and other high-tech products in Korea. Resolving this issue, which is now being discussed by a dispute panel at the World Trade Organization, may be a prerequisite for progress toward a Korea-China-Japan FTA. While negotiations for an FTA are likely to lengthy and difficult, the benefits of a high-level agreement would be large, as China is the largest trading partner of both Japan and Korea, and they are China’s third and fourth largest markets, respectively.

Should Korea join the CPTPP?

Joining the CPTPP would only bring one more country (Mexico) into an FTA with Korea. Nevertheless, the economic benefits of belonging to a high-level trade agreement would be significant, in part by allowing the government and the business sector to stay in tune with new norms and rules for international commerce. The political benefits are also significant, especially if the United States were to join the CPTPP. Mason Richey, professor at Hankuk University of Foreign Studies said that “there is also the political advantage of joining another deal (the CPTPP) with Japan, adding momentum to the recent RCEP deal, which also includes Japan. This is salutary for South Korea’s relations with Japan and the U.S., critical partners in the Northeast Asia region.” At the December 8th ceremony, President Moon said that he will “continue to consider” joining the CPTPP. A presidential aide noted that the CPTPP and RCEP are complementary rather than contradictory, but that now is not the right time for Seoul to decide whether to join the CPTPP. One concern is how China would regard Korea’s accession to the CPTPP.

Becoming a member of the CPTPP would also entail costs, such as complying with environmental and labor standards, and rules for state-owned enterprises. In addition, the existing 11 member countries may impose conditions on countries that apply for membership. While no additional countries have been added to the group, the United Kingdom announced in June 2020 that it would like to join. Presumably, the 11 member countries would start bilateral negotiations with any new candidates, including Korea, using it as opportunity to resolve outstanding issues. In the end, the decision on whether to join the CPTPP may hinge on how high the cost is of meeting the demands imposed by the existing member countries.

Randall Jones is a Non-Resident Fellow at the Korea Economic Institute of America. The views expressed here are the author’s alone.

Image from wwian’s photostream on flickr Creative Commons.