The Peninsula

Korea’s Healthcare System Part II: Policies to Contain the Growth of Healthcare Spending

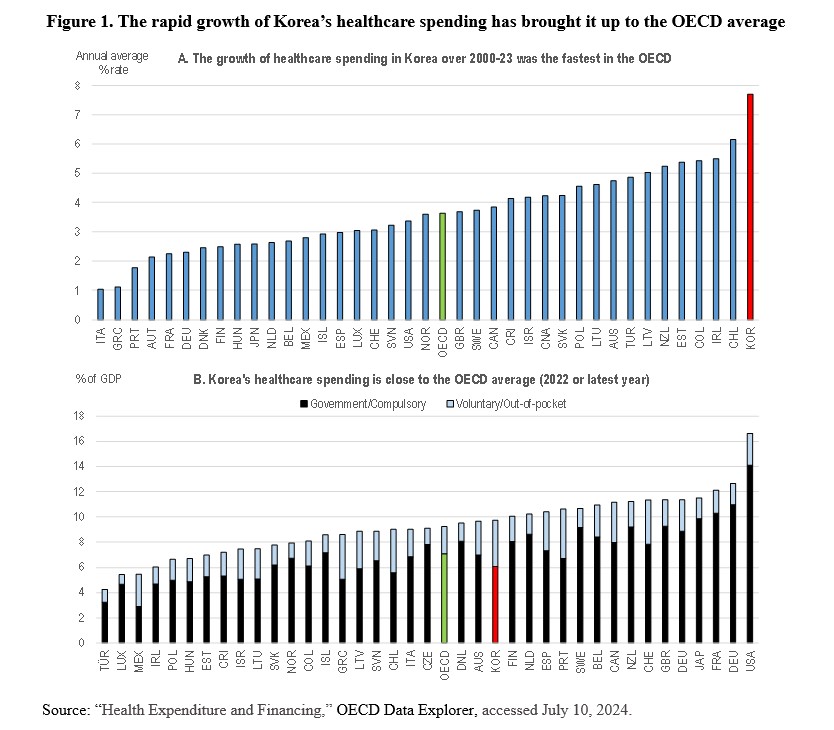

Korea’s healthcare spending in 2000 was the lowest among the 38 OECD countries at less than 4 percent of GDP, reflecting the country’s relatively young population and the limited coverage of its National Health Insurance (NHI). However, adjusted for inflation, healthcare spending grew at an annual rate of 7.7 percent from 2000 to 2022, the fastest in the OECD (Figure 1, Panel A). By 2022, Korea’s healthcare spending was slightly above the OECD average at 9.7 percent of GDP (Panel B). In addition, Korea’s per capita healthcare outlay of 4,570 USD (using purchasing-power-parity exchange rates) in 2022 was near the OECD average.

The Korean government’s continuing expansion of the range of services covered by the NHI has contributed to the increase in healthcare spending. In 2017, the government launched a plan to extend NHI coverage to all health services except non-essential care, such as cosmetic surgery, by 2022. For example, MRI and ultrasound scans have been added to the NHI. The OECD projected in 2019 that the growth in Korea’s healthcare spending over the period between 2015 and 2030 would be the fastest among the OECD countries.

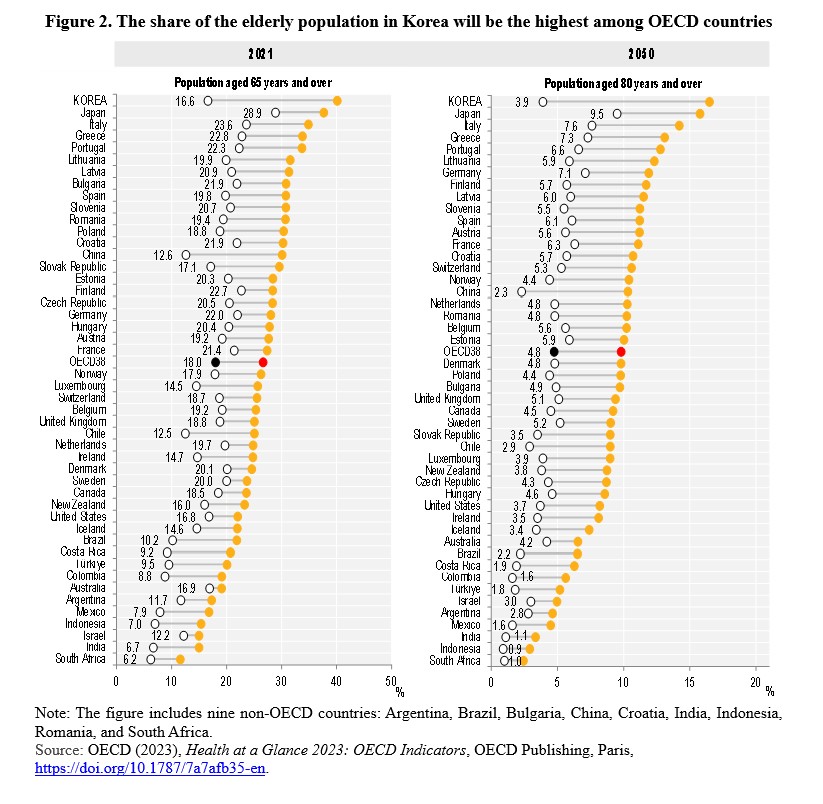

Another key factor driving healthcare spending is Korea’s rapidly aging population. Per capita healthcare spending on Koreans aged 65 and above is more than four times higher than for those under 65. The share of Korea’s population aged 65 and older is projected to jump from 16.6 percent in 2021 to 40.1 percent in 2050, the largest increase among the OECD countries (Figure 2). Moreover, the share aged 80 and above is expected to rise from 3.9 percent to 16.5 percent (Figure 2). By 2050, the share of the elderly in Korea will be the highest in the OECD. Korea’s elderly dependency ratio (the number of persons aged 65 and above relative to those aged 20 to 64) is projected to jump from 26.2 percent in 2022 to 84 percent in 2050, again the highest among OECD countries. This implies a drop in the number of elderly per working-age population from 3.8 to 1.2 over that period.

Rapid demographic change makes it essential to improve the efficiency of Korea’s healthcare system to contain the rise in spending. Key priorities to achieve this goal include promoting healthy aging and reducing the overreliance on hospitals.

Promoting Healthy Aging

Korea’s life expectancy in 2021 was 83.6 years, the second longest among OECD countries. However, a longer life expectancy does not necessarily imply a longer, healthier life. In Japan, for example, the correlation between life expectancy and a healthy lifespan (defined as the number of years a person can continue daily life without health-related constraints) across the country’s 47 prefectures is low.

Korea’s healthy life expectancy was 73.1 years in 2019, well above the United Kingdom (70.1 years) and the United States (66.1 years) and nearly on par with Japan (74.1). Further promoting healthy aging is key to containing healthcare costs. In Japan, a healthy lifespan by prefecture is positively correlated with lower per capita healthcare costs for persons aged 75 and older and higher labor force participation rates for those aged 65 and older. This may reflect a positive effect of employment on the mental and physical health of older persons. Policy measures in several areas, such as diet and tobacco use, would further extend Korea’s healthy lifespan, thereby enhancing well-being and containing the growth of health and long-term care expenditures.

Diet and Exercise

The leading causes of death in Korea are strokes, heart disease, and lung cancer, which are related to lifestyle. Korea is well-known for its healthy cuisine. Indeed, 99 percent of its adult population in 2021 reported eating vegetables daily, the highest in the OECD (OECD, 2023, p. 93). In addition, nearly half devoted at least 150 minutes per week to physical activity, matching the OECD average (OECD, 2023, p. 93). Healthy lifestyles have enabled Korea to limit the problem of obesity, which is common in most advanced countries. In 2021, less than one-third of adults reported being overweight, the lowest in the OECD and well below the OECD average of 54 percent (OECD, 2023, p. 95).

However, among children aged 5 to 9, the share who are overweight has risen to one-third, matching the OECD average (OECD, 2019, p. 99). Studies show that the rising number of children and adolescents who skip breakfast, eat fast food, and consume sugary drinks has increased the share of children who are overweight. Education and incentives to encourage the benefits of a traditional diet would help limit the obesity problem.

A second concern is tobacco, given that lung cancer is a leading cause of death in Korea. Although the share of smokers has declined, 26 percent of men over the age of 15 smoked daily in 2021, the ninth highest proportion among OECD countries (OECD, 2023, p. 87). In contrast, less than 5 percent of women smoked daily, given that it is less socially acceptable for women to smoke in public (OECD, 2023, p. 87). The price of a pack of 20 cigarettes in Korea in 2020 was 3.86 USD, only half of the OECD average, indicating that the price should be increased to discourage smoking (OECD, 2022, p. 193).

Consumption of alcohol is another concern, given that high alcohol intake is a significant risk factor for heart diseases, strokes, liver cirrhosis, and certain cancers. The per capita consumption of alcohol by adults in Korea in 2021 was 10 percent below the OECD average. However, the share of men (7.7 percent) and women (3.4 percent) who were classified as “dependent drinkers” in 2016 was the ninth and third highest, respectively (OECD, 2019, p. 91). While taxes on alcohol are already relatively high, addressing the issue of alcohol dependency may be helpful.

Reducing Over-reliance on Hospitals

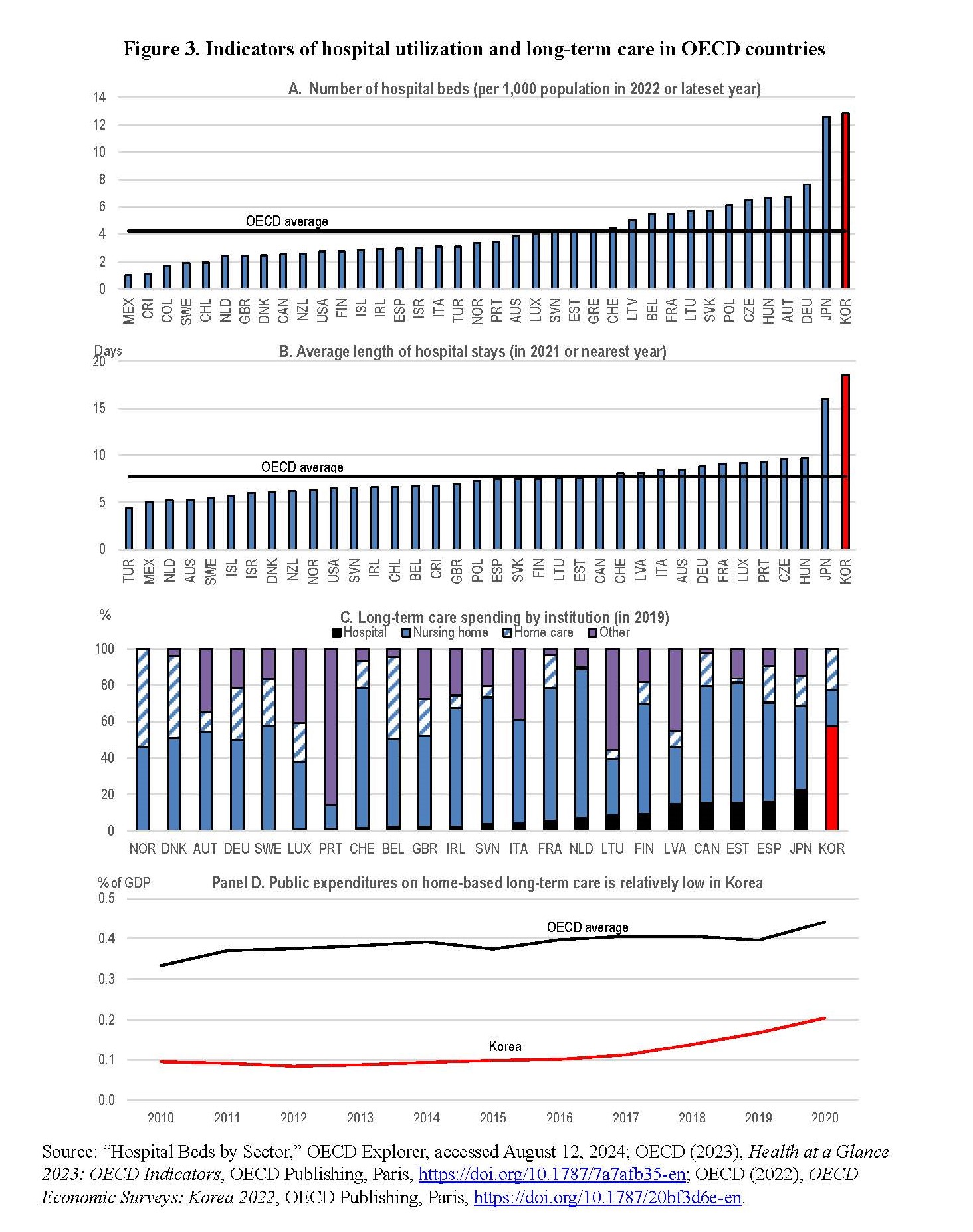

The number of hospital beds in Korea increased 2.5 times from 2004 to 2022 while declining by more than 3 percent among the OECD countries. Consequently, the number of hospital beds (per 1,000 population) in Korea in 2022 was 12.9, the highest in the OECD and triple the OECD average (Figure 3, Panel A). Moreover, the average length of stay, at 18.5 days, was the longest in the OECD in 2022 (Panel B). The exceptionally large number of hospital beds and the long duration of hospitalization are significant factors driving up Korea’s healthcare spending.

The rising share of the elderly who require long-term care (nursing care and assistance) is a major factor driving up hospitalization rates. Long-term care in Korea was traditionally a family obligation. In a 2006 government survey, 67.3 percent of Koreans believed that caring for elderly parents was a family responsibility. However, that view was only held by 32.6 percent in 2016. The introduction of universal long-term care insurance (LTCI) in 2008 accelerated the shift in public opinion. Korea was the second Asian country, after Japan, to introduce a social insurance system that provided comprehensive universal long-term care coverage for the elderly.

The large number of hospital beds and the lengthy average stay in Korea are partly due to “social hospitalization” – the provision of in-patient care in hospitals to elderly persons whose health conditions are stable and do not require medical treatment. A key objective of the LTCI is to “de-medicalize” long-term care and reduce financial pressures on the NHI. However, this goal has not been achieved. The Ministry of Health and Welfare estimated that “social admissions” in 2019 accounted for about 40 percent of patients in long-term care hospitals. Most of these patients faced challenges associated with physical dysfunction and cognitive impairment, which would be better treated in long-term care institutions rather than in hospitals. In addition, the average stay at long-term hospitals was 165 days in 2019. As a result of social hospitalization, 57.5 percent of long-term care spending went to hospitals in 2019 (Figure 3, Panel C). The share among other OECD countries with relevant data was less than 16 percent, except for Japan.

Policies to Take Long-term Care Out of Hospitals

Reducing financial incentives that favor relying on hospitals (which are covered by NHI) for long-term care would help de-medicalize the practice by moving it to long-term care institutions (covered by LTCI). For instance, harmonizing the reimbursement scheme between the NHI and the LTCI would reduce the incentives to use long-term care hospitals. Another option is to impose additional charges for those who remain in hospitals after their medical care has ended. Finally, increasing the quality of the primarily private long-term care institutions would lower the demand for long-term care hospitals.

Greater emphasis on home-based long-term care for the elderly would also be beneficial. Many countries prioritize home-based care, when possible, to minimize costs and better meet the needs of the elderly. Although Korea’s public spending on home-based care doubled from 0.1 percent of GDP in 2015 to 0.2 percent in 2020, it remains less than half of the OECD average (Figure 3, Panel D). Korea faces a shortage of accessible, affordable, and high-quality home-based care. Indeed, while the number of total care recipients has more than doubled since 2009, the share of the elderly receiving home-based services has fallen, reflecting insufficient financial and human resources, notably a shortage of long-term care home nurses. Evidence suggests that visiting nurse services are associated with shorter stays in long-term care hospitals and lower healthcare costs. The nurse shortage reflects unstable work contracts and difficult working conditions. Greater use of foreign nurses would be beneficial, but they must pass the national examination, which is held in Korean only.

Conclusion

Rapid population aging is expected to drive a significant increase in Korea’s public social spending, which is projected to nearly double from 12.2 percent of GDP in 2019 to 23.3 percent by 2060. Healthcare expenditures are expected to account for about one-third of the increase. Meeting the fiscal challenges of aging should be facilitated by enhancing the efficiency of healthcare to limit rising costs while continuing to improve the quality of the healthcare system in line with technological progress. Policies to promote healthy aging and reduce the overuse of hospitals are essential to meet this challenge. In addition, shifting out-patient care away from its fee-for-service payment system, as discussed in Part 1 of this series, is a priority. Healthcare reforms are also needed to ensure universal access to the healthcare system, which will be discussed in Part 3 of this series.

Randall S. Jones is a Non-Resident Distinguished Fellow at the Korea Economic Institute of America. The views expressed here are the author’s alone.

Photo from Shutterstock.

KEI is registered under the FARA as an agent of the Korea Institute for International Economic Policy, a public corporation established by the government of the Republic of Korea. Additional information is available at the Department of Justice, Washington, D.C.