The Peninsula

Improving Korea’s Long-Term Care for the Elderly

Spending on long-term care is increasing rapidly in many countries in line with population aging. Long-term care is defined as nursing care and assistance that enables elderly persons to live independently. Elderly care in Korea has traditionally been a family responsibility. A 2006 government survey reported that 67.3% of Koreans believed that caring for older parents is a family responsibility, but that view was held by only 32.6% in 2016. The shift was likely accelerated by the introduction of universal long-term care insurance (LTCI) in 2008. Korea was the second Asian country after Japan to introduce a social insurance system that provided comprehensive universal long-term care coverage for the elderly.

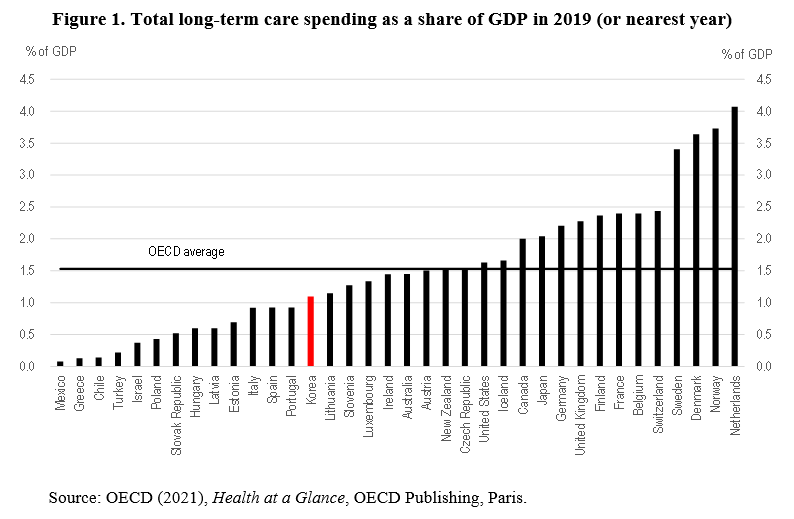

Long-term care expenditures under the LTCI increased at a 15.2% annual average rate over 2009-18, outpacing the rise in the number of recipients rose at a 9.3% rate. While the public LTCI finances long-term care, private-sector entities provide most of the care. Indeed, the number of long-term care facilities and care workers tripled during the first decade of the LTCI. Still, long-term care spending remained relatively low as a share of GDP at 1.1% in 2019, compared to more than 3% in the Netherlands and some Nordic countries (Figure 1), reflecting Korea’s relatively young population.

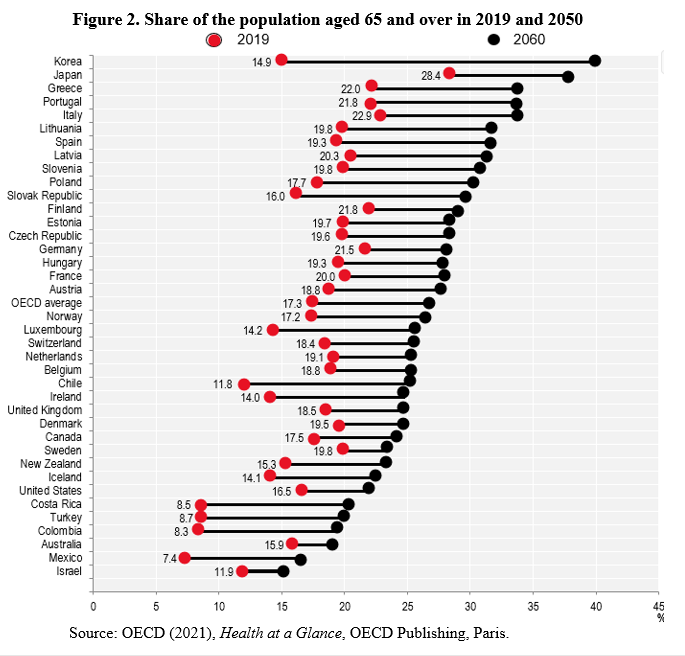

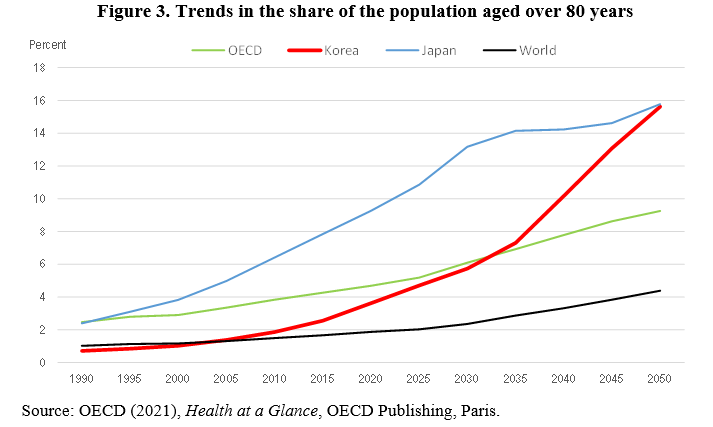

However, rapid population aging in Korea is likely to increase long-term care expenditures significantly. In 2019, 14.9% of the Korean population was aged 65 or older (Figure 2), compared to the OECD average of 17.3%. By 2050, though, the share is projected to reach 40%, the highest among OECD countries. Moreover, the share aged 80 and over – the age group where long-term care needs are the greatest – is projected to rise from less than 4% to 16% by 2050, matching Japan (Figure 3).

Addressing the issue of social hospitalization

One of the main objectives of LTCI was to reduce “social hospitalization,” defined as the elderly receiving in-patient care in hospitals even though their health conditions are stable and they do not require medical treatment. In other words, the LTCI was intended in part to “de-medicalize” long-term care and reduce the financial pressure on Korea’s universal National Health Insurance (NHI). This objective has not been achieved, as explained in the 2022 OECD Economic Survey of Korea.

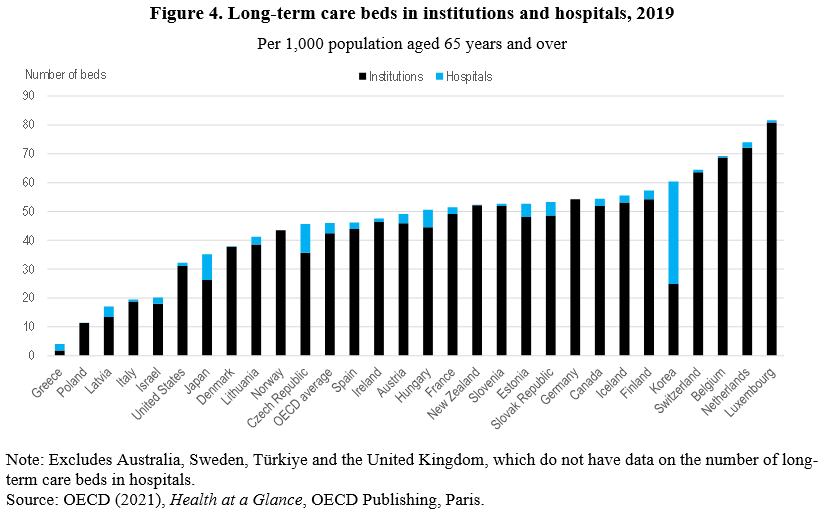

Korea has a relatively large number of long-term care beds at 60 per 1,000 elderly persons compared to the OECD average of 46 (Figure 4). However, 59% of them are in long-term care hospitals, which are supposed to focus on services such as sub-acute care, palliative care, and rehabilitation services. The Ministry of Health and Welfare estimated that “social admissions” accounted for around 40% of patients in long-term care hospitals in 2019. Most of these patients faced problems of cognitive impairment and physical dysfunction and would receive better treatment in long-term care institutions. Moreover, the average stay at long-term hospitals was long at 165 days in 2019. Social hospitalization leads to inefficient use of resources, as many patients who need medical care at long-term care hospitals cannot receive it because of a lack of available beds. The Ministry estimated that around 30% of the elderly who stay in long-term care institutions need hospital care but do not receive it.

Patients tend to prefer long-term care hospitals (covered by NHI) because of the financial advantages compared to long-term care institutions (covered by LTCI). Unlike the LTCI, the NHI has ceilings on copayments by patients. In particular, elderly persons who prefer long hospital stays have an incentive to choose long-term care hospitals. Harmonizing the LTCI and NHI reimbursement schemes and imposing additional charges on those who remain in hospitals after their medical care has ended would reduce social admissions. Long-term care hospitals also benefit from social admissions. Given the flat-rate per diem reimbursement, long-term care hospitals cherry-pick low-cost patients with minimal medical issues. Adjusting the flat-rate payment system based on the severity of patients’ illnesses would reduce social admissions. Finally, the quality of the mostly private long-term care institutions and home care should be upgraded to reduce demand for long-term care hospitals. Better monitoring of long-term care facilities by local governments and the National Health Insurance Service could improve their quality.

Expanding home-based care

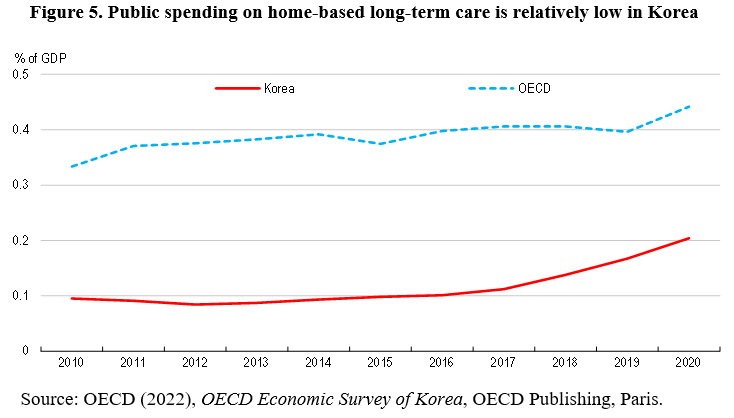

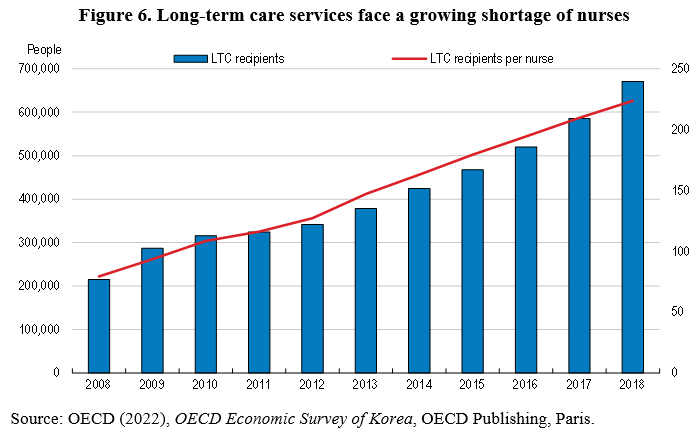

Many OECD countries are focusing on home-based long-term care for the elderly to minimize costs and better meet the needs of the elderly. However, Korea faces a shortage of accessible, affordable and high-quality home-based care. Indeed, the share of the elderly using home-based services has declined since 2009, while the number of total care recipients more than doubled. The shortage of home-based care reflects insufficient financial and human resources. Public spending on home-based care is less than half the OECD average (Figure 5), while the number of long-term care home nurses has barely increased (Figure 6). This is inefficient, as evidence suggests that visiting nurse services are associated with lower health care costs and shorter stays in long-term care hospitals. The shortage of nurses is blamed on low wages, unappealing working conditions and unstable contracts. Foreign nurses can work only after passing the national examination, which is held in Korean only.

Conclusion

The OECD projects that public social spending will double from 12% in 2019 to 23% in 2060, driven by population aging. Spending on long-term care will contribute to this increase. The LTCI premium is 0.7% of income, which is still well below Germany (3.05%) and Japan (1.5%), but is likely to increase significantly. It is important that the government implement policies to provide high-quality long-term care to the elderly efficiently through a number of reforms. First, Korea should harmonize the LTCI and NHI reimbursement schemes, in part to reduce social hospitalization. Second, Korea needs an integrated long-term care system with greater specialization and coordination among hospitals, long-term care institutions, home-based care and primary care. Third, the government should improve and expand home-based care in part by increasing the number of home-care nurses.

Randall S. Jones is a Non-Resident Distinguished Fellow at the Korea Economic Institute of America. The views expressed here are the author’s alone.

Photo from Shutterstock.