The Peninsula

How Does South Korea’s New Election System Work?

Published April 15, 2020

Category: South Korea

By Soo Jin Hwang

Last year, South Korea adopted a new mixed-member proportional representation (PR) system. The revision aimed to improve representation by making it easier for previously underrepresented political parties to win a larger share of seats in the National Assembly. Simultaneously, it was a politically advantageous move for the ruling Democratic Party (DP), which calculated that opposition parties would lose more influence in the legislature. Aware that the new PR system would likely disadvantage its chances at the polls, the main opposition United Future Party (UFP) – until recently the Liberty Korea Party – tried to hedge by creating a satellite party. This prompted the DP to take similar measures in response. As a consequence of these maneuvers, voters at today’s election received the longest ballot in Korea’s election history. More pressingly, these countermeasures by the major parties may ultimately undercut the effort to make politics more inclusive.

How does the new system work?

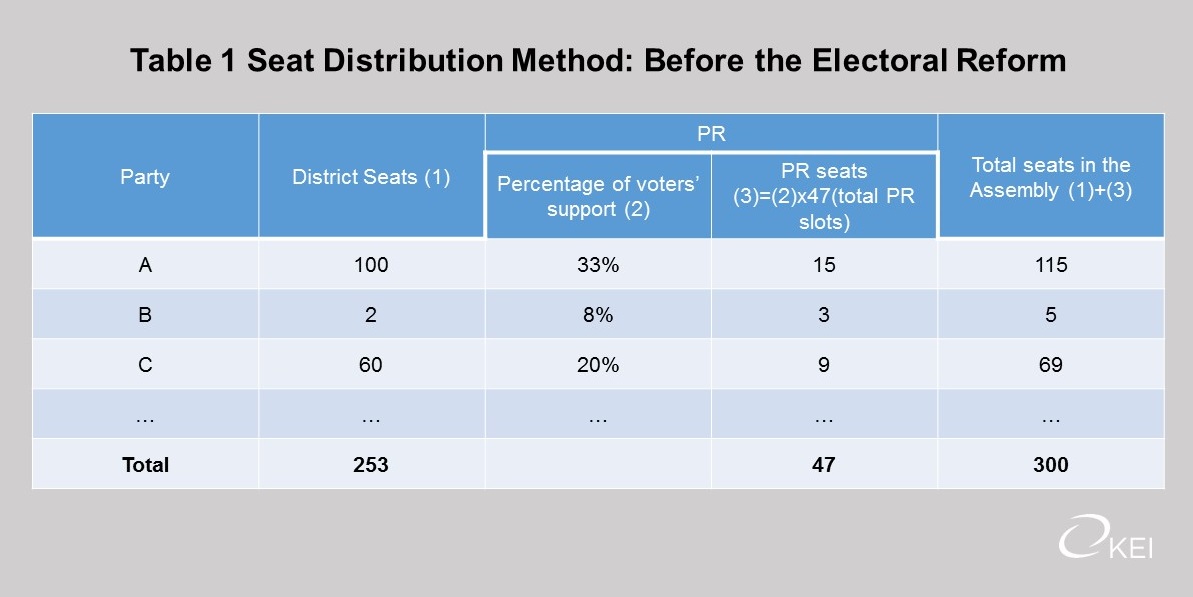

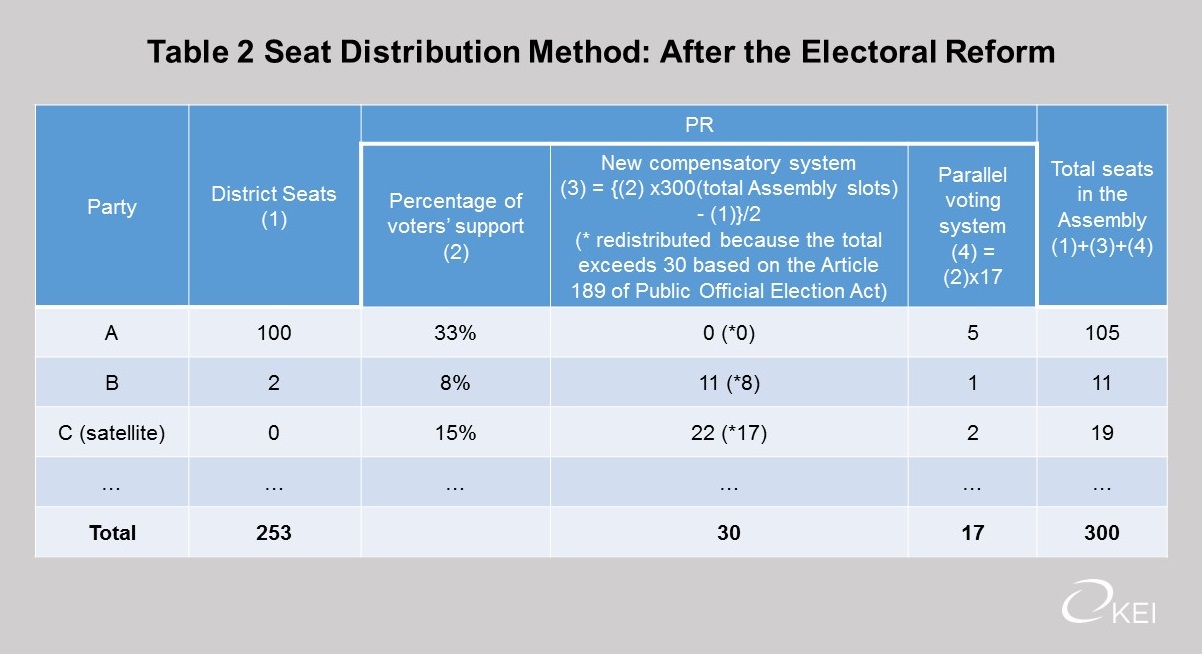

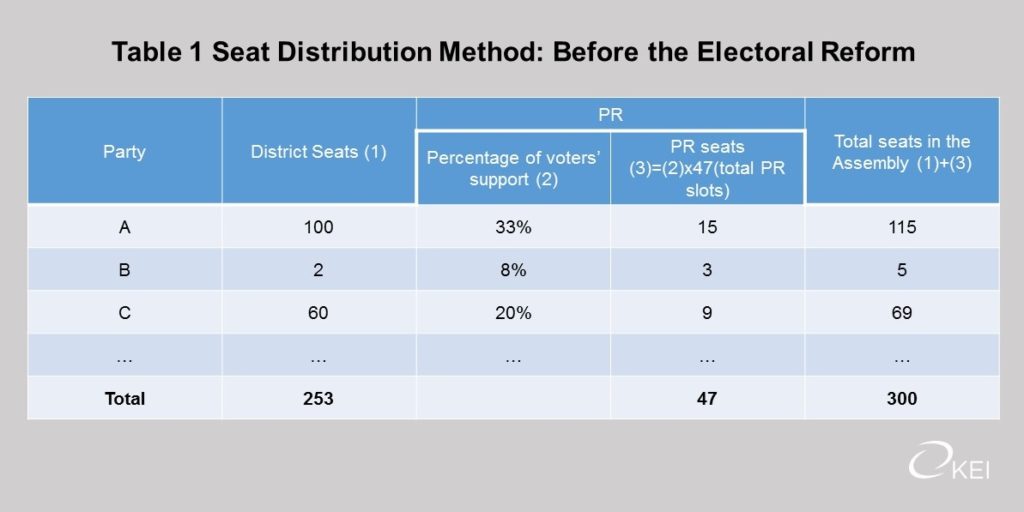

The revised PR system disadvantages major parties because it distributes proportional seats based on the new “compensatory system.” The new calculation aims to offset overrepresentation from district seat races (determined through first-past-the-post voting). Of the 47 seats reserved for PR, 30 are allocated through the new compensatory system which subtracts the number of district seats that the party won from the percentage of votes cast for the party, and then divides the number by two.

The remaining 17 slots are allocated based on the “parallel voting system” which has been used for all PR seat distribution before the reform. For instance, Table 1 and Table 2 shows that Party A gets less, and Party B gets more seats under the new law.

Political Maneuvering Around Electoral Reform

Since parties that won more district seats would be awarded fewer seats reserved for PR, this new electoral system was disadvantageous for bigger parties. The purpose of the revision was to allow minor parties to be better represented in the legislature and make South Korean politics, traditionally dominated by two major parties, more inclusive.

Aware that this new electoral system would cost them seats, the main opposition party tried to prevent the bill from passing. By contrast, the ruling DP pushed hard to pass the bill because it maintains close relations with smaller liberal parties. Together, they agree on several essential platforms. As a result, the DP saw the electoral reform as a vehicle to empower their ally parties while reducing UFP’s seats.

When the electoral reform bill was finally passed, UFP introduced a satellite party, Future Korea Party (FKP), which would only compete for PR seats. This was an effort to offset the number of seats that the conservative opposition party would lose under the new compensatory system. In response, the ruling DP formed Together Citizens’ Party (TCP) to counter UFP’s tactics. Both UFP and DP were criticized for these maneuvers.

Despite the public criticism, the two parties still considered the creation of satellite parties to be advantageous. As evident in the scenarios laid out in Table 1 and Table 2, Party C – which would have gained a total of 9 PR seats under the previous electoral system – can gain around 19 PR seats with a satellite party under the new system. Party A, in Table 2, has more than twice of support than party C, and yet, only receives 5 PR seats.

Implications

The reform is not likely to bring immediate change in the South Korean political landscape. By raising the chances of minor parties winning more seats in the National Assembly, the new system did prompt several organizations and new minor parties to register and run in today’s election . For instance, North Korean refugees in South Korea created a political party for the first time. There is also a party called Chungcheong Future Party, which only focuses on constituencies in Chungcheong Province.

Many other groups sought to launch a party this year, but failed to meet the minimum number of registered members required to compete in the election. Nonetheless, their pledges are still eye-catching. For example, Marriage Future Party is a party that is focused on assisting with marriages and childcare. Another example is the Nuclear Party that supports South Korea’s withdrawal from the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT) and building nuclear weapons.

Merits of these political platforms aside, unless the two major parties embrace the reform without trying to bypass it with their satellite parties, these new minor parties are unlikely to achieve anything more than making the ballot longer for voters on election day.

Soo Jin Hwang is currently an intern at the Korea Economic Institute. She holds a master’s degree in Security Studies from Georgetown University. The views expressed here are the author’s alone.

Picture from user Republic of Korea on Flickr