The Peninsula

Unpacking the U.S.-South Korea Trade Deal

Published July 31, 2025

Author: Tom Ramage

Category: Economics, Economic Security, The United States

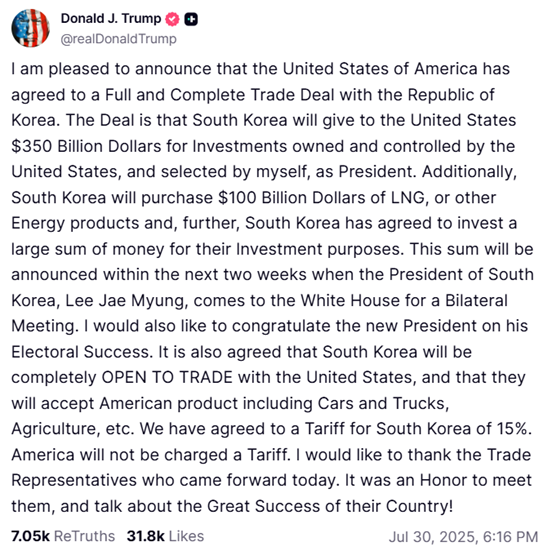

The United States and South Korea struck a trade deal on July 30, establishing a 15 percent baseline tariff rate two days before a 25 percent rate was scheduled to go into effect. The main aspects are likely to take full form over the next few weeks, pending statements and fact sheets from Washington and Seoul, as well as a leader-level summit in Washington.

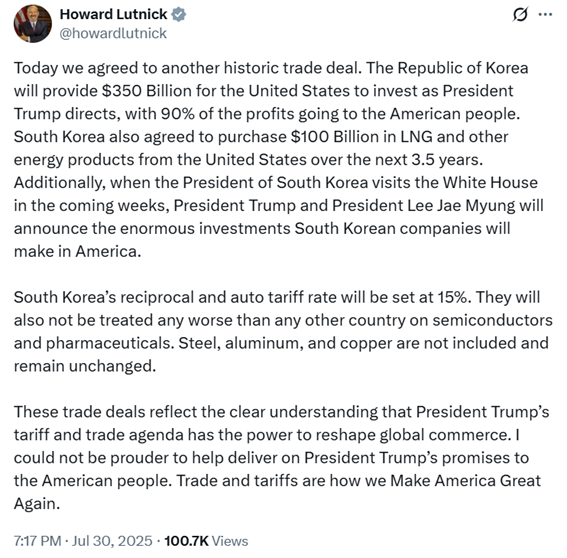

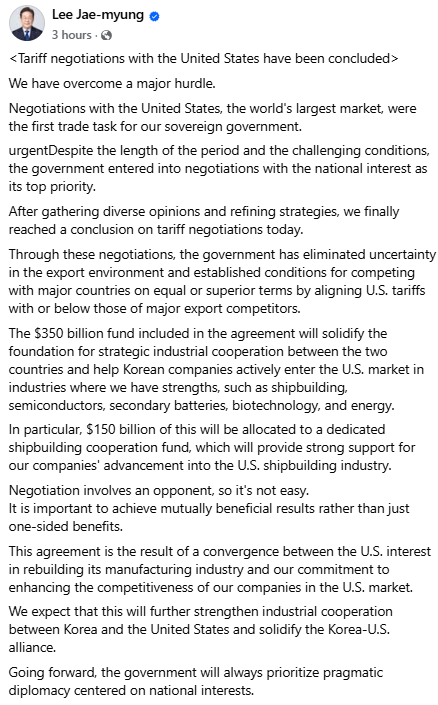

President Donald Trump revealed the main parameters of the deal on social media, while Secretary of Commerce Howard Lutnick, Korean President Lee Jae Myung, and other Korean officials provided additional details in separate posts and commentary. The bottom line is that Korea agreed to massive investments and purchases in and from the United States to secure a 15 percent rate on exports, including for autos, which is particularly important as autos represent Korea’s largest export to the country. Korea also agreed to expand domestic market access for U.S. cars and agricultural products, with the apparent exception of the rice and beef markets.

Reaching such a deal before August 1 allows Korea to compete with trading partners such as the European Union and Japan on a level playing field, as these trade partners also have deals that set their tariff rates at 15 percent, which likewise encompass autos. This means Korean products in the U.S. market will not find their goods tariffed higher than their industry peers. At the same time, however, the deal effectively bypasses the U.S.-Korea Free Trade Agreement (KORUS FTA).

President Trump’s post on Truth Social announcing the deal with South Korea.

The Art of the U.S.-Korea Deal

The first tradeoff from Korea in exchange for tariff reductions comes from a USD 350 billion Korean investment fund for U.S.-based investments. Trump has indicated this will be “owned and controlled by the United States,” with Lutnick adding that “90 percent of the profits will go toward the American people.” As in the Japan deal, the investment fund is set to target strategic industries. President Lee’s statement on the deal indicated it would be used to “help Korean companies actively enter the U.S. market in industries where [Korea] has strengths, such as shipbuilding, semiconductors, secondary batteries, biotechnology, and energy.” USD 150 billion of the fund will go toward shipbuilding cooperation, providing fertile ground for additional inroads by Korean firms in the sector.

President Trump claims he alone will select the investments Korea makes. It remains to be seen under what time frame the Korean investment fund will operate. For example, the fact sheet for the EU deal sets the USD 600 billion of pledged investments to follow a timeline through 2028—which is the end of Trump’s current term. It is also unclear whether the USD 350 billion is just a ceiling, as the number for the Japanese fund is. Trump also indicated that “a large sum of money” would be announced for Korea’s “investment purposes,” following a planned visit by President Lee to the White House “in two weeks.” Whatever is announced could make up some of the largest components of the deal.

Beyond that, Korea will commit to purchase USD 100 billion of liquefied natural gas (LNG), “or other energy products,” which Lutnick further indicated would occur over a three-and-a-half-year time frame. As to what forms of “other energy products” this could comprise, further details will have to come out in additional fact sheets or announcements.

U.S. Secretary of Commerce Howard Lutnick’s post on X clarifying aspects of the deal, including auto tariffs at 15 percent.

Market Access

Next comes the side of the deal affecting U.S. access to Korean markets. The new deal with Korea is set to expand the U.S. footprint in Korea’s agricultural market, putting it in line with the deals with Europe and Japan. The new terms appear to have allowed Korea not to cross what it considers a red line on beef and rice market access. Instead, Korea’s Chief Presidential Secretary for Policy Kim Yong-beom stated that “both sides agreed not to further open Korea’s rice and beef markets,” citing food security concerns and the sensitivity of Korea’s agricultural sector.

Given that the KORUS FTA had already set the beef tariff at zero percent from 2026 onward and that the rice tariff had already been at the 5 percent most-favored nation (MFN) rate of 5 percent for the in-quota amount, this appears to be a win-win solution for both countries. Additional details will likely reveal new information on what agricultural products will actually be covered under the agreement for Korea to “accept American products,” given that quotas and regulations on beef and rice appear to remain in place.

The deal with Korea also opens the Korean market to U.S. cars. Korea’s regulations on safety standards for autos have historically been deemed by the United States as a non-tariff barrier for U.S. car companies. The KORUS FTA had allowed up to 50,000 U.S. autos to enter Korea under U.S. safety standards rather than Korean standards, while also adjusting some of the fuel economy standards that had remained in place. While language on this was absent from President Trump and Secretary Lutnick’s statements on the deal, Korea’s presidential office said the country is lifting the 50,000 limit on U.S. auto imports.

Korean media reports indicate that no U.S. carmaker exports over that limit, meaning the negative impact on Korea is likely minimal. But now that Korea is receiving the same tariff rate for autos as countries that previously imported them under the 2.5 percent MFN tariff rate, the benefits that Korea had been receiving under the KORUS FTA—namely, the previous zero percent tariff on autos—appear null, unless further adjustments or renegotiations are made.

The English translation of President Lee Jae Myung’s Facebook post describing aspects of the U.S.-Korea deal.

Digital Trade Left Untouched?

Standing in contrast to the recent EU deal (or at least the U.S. presentation of it), digital service policies are not set to be part of the deal. This had been a persistent point of pressure in U.S.-Korea negotiations. For now, Korea seems to have come out ahead of Europe on digital services, as the European deal has set the issue aside as something the two sides “intend to address.”

All that in mind, President Lee’s visit to Washington, apparently set for mid-August, is likely to shore up some of the matters unspoken. Ongoing burden-sharing negotiations, individual company investment commitments, and progress on issues such as foreign exchange policies could form part of a greater package deal that ties together both trade and defense. It was wise to get an outline of a deal ahead of the deadline to avoid the tariffs that may befall countries that did not make as robust an effort to negotiate, and the contours of the preliminary U.S.-Korea agreement seem to play to Korea’s economic and industrial strengths.

Still, questions remain regarding the overall architecture of the deal. Is it a trade deal in the traditional sense? Will it require any form of ratification by either side? What is the likelihood of this occurring? Would this prompt it to be negotiated further? Moreover, different components of the deal appearing in different statements by those involved, such as the agricultural provisions mentioned by the South Korean government but not U.S. officials, offer an opportunity for both sides to provide clarity on the full terms of the deal.

Other developments may come from the final rulings on the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA) tariffs and their subsequent effects on the implementation of the Trump administration’s “America First” trade agenda—for better or for worse. Korean Trade Minister Yeo Han-koo has also indicated that there could be continued efforts by the U.S. side to change trade terms, such as through pressure to remove non-tariff barriers. Regarding auto tariffs, Yeo also stated that “if opportunities arise [Korea] will strive to lower the rate by even 1 percent.”

For now, those watching U.S.-Korea trade developments should wait and see what more might emerge from a White House summit between the two leaders and take stock of potential new commitments that may come out of the already robust relationship between the two countries on technology, industrial cooperation, economic security, and trade.

Tom Ramage is Economic Policy Analyst at the Korea Economic Institute of America (KEI). The views expressed are the author’s alone.

Photo from the White House Flickr account.

KEI is registered under the FARA as an agent of the Korea Institute for International Economic Policy, a public corporation established by the government of the Republic of Korea. Additional information is available at the Department of Justice, Washington, D.C.