The Peninsula

What the Japan and EU Trade Deals Mean for South Korea

Published July 30, 2025

Author: Tom Ramage

Category: Economic Security, Economics, The United States

In the past few days, the United States inked trade deals with Japan and the European Union, supplementing those already cemented with the United Kingdom, the Philippines, Indonesia, and Vietnam. As major trading partners of the United States, the contours of the deals with Japan and the European Union shed some light on what a realistic deal with South Korea may look like, but also what South Korea may have to contend with.

Both deals appear only to be frameworks, but there are major implications in the details. First, both Tokyo and Brussels have reached a tariff rate of 15 percent—down from an original 24 percent for Japan and 20 percent for the European Union. Most consequential for Korea, the European Union will receive a set rate sectoral levy on autos and auto parts, pharmaceuticals, as well as semiconductors also at 15 percent (the U.S. Department of Commerce is expected to announce the results of its Section 232 investigation on semiconductors in the next two weeks). Steel, aluminum, and copper tariffs will remain at 50 percent. Reuters similarly reported clarification from Prime Minister Shigeru Ishiba that Japan’s auto and auto part tariffs will drop 10 percentage points to 15 percent, although this specific feature was missing from a fact sheet the White House published.

The United States receives an investment fund from Japan with a ceiling of USD 550 billion—which Washington gets 90 percent of the profits from—including for liquified natural gas (LNG) pipeline investment. This comes along with the expansion of import quotas on U.S. agricultural products such as rice, purchase commitments for agricultural products, Japanese purchases of Boeing aircraft and U.S. defense equipment, and promises toward the reduction of regulatory barriers for U.S. autos in the Japanese market.

As part of a commitment to work together on supply chains for nine strategically important industries ( indicated by the Japanese government fact sheet) the investment fund will focus on semiconductors, pharmaceuticals, steel, shipbuilding, critical minerals, aircraft, energy, automobiles, and AI and quantum technologies.

The European package similarly includes a USD 600 billion investment into the United States, USD 750 billion in purchase commitments for U.S. energy through 2028, addressing of digital service policies, elimination of certain tariff and non-tariff barriers for U.S. products, and purchases of U.S. military equipment. Importantly for digital services policies, the White House’s EU trade deal fact sheet noted an “inten[tion] to address” the issues, but such provisions were seemingly absent from the European Union’s own version of the deal, prompting questions about where the United States might meet other countries like Korea on the matter.

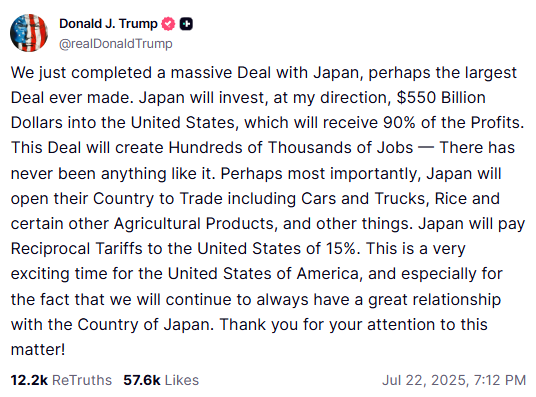

President Trump’s Truth Social post announcing the Japan deal from July 22.

What Seoul May Expect

According to the International Trade Centre’s Trade Map, automobiles were Korea’s number one export item to the United States in 2024, at USD 42.97 billion (roughly 33 percent of their total exports to the country). The 15 percent tariff on autos and auto parts from Japan and the European Union sets a new baseline for the imposed auto tariffs on countries that can come to a deal. Consequently, this gives Japanese and European manufacturers an advantage—even against U.S. automakers—unless more trade agreements or exemptions are made.

Under the new terms of trade, not only must U.S. auto manufacturers import cars assembled abroad at the higher 25 percent rate, but U.S. manufacturers typically rely heavily on Mexican, Canadian, and South Korean intermediate goods that will still face the 25 percent tariff levels. Additionally, the opening of the Japanese market to U.S. agricultural products raises some questions about what sort of concessions will be expected of Korea’s own agricultural market, which contains certain limitations on the import of U.S. beef and rice.

As for the European Union—the United States’ number one total trading partner when considering it as a single regional entity—the flat rate set for semiconductors may also offer some insight for Korea. This is particularly salient considering what could happen in light of the 232 investigations into Korea’s chip exports to the United States, given that the results of the investigation are set to come out after the August 1 deadline. There is also some light shed on this through the Tokyo deal. The Japanese term sheet notes regarding semiconductors that “even if sector specific tariffs are imposed, Japan will not be treated as inferior to other countries,” boding well for making a deal even while 232 investigations are ongoing.

In the digital sector, the incongruities between the United States and Belgium regarding their deal on digital services may impact how the United States and South Korea negotiate on the issue. National Economic Council Director Kevin Hassett has stated that he expects the removal of digital service taxes as part of trade deals with partners. Similarly, Congress has added pressure to include it as a component of U.S.-Korea negotiations on trade. Indeed, the Office of the U.S. Trade Representative’s 2025 National Trade Estimate Report on Foreign Trade Barriers indicated network usage fees for U.S. companies potentially benefiting Korean competitors, competition policy, data localization regulations, and regulations on cloud service providers as some of the unresolved digital barriers to trade. It is possible that in order to make a deal within a preferred timeframe, Washington may defer to the authority of Korea’s legislature to alter and amend regulations, and these sectors could potentially be left off as a “commitment to continue to negotiate,” as appears to be the case for the European Union.

In any case, to make a fair comparison, it should be acknowledged that Korea is not trading like the European Union or Japan. Unlike the majority of countries, Korea has a free trade agreement (FTA) in place with the United States. Even with low effective tariff rates prior to deals with the European Union or Japan, this fact alone may present a fundamentally different situation as to where negotiations should start and for what issues they should cover. Will existing FTA agreements be abrogated? Would a deal factor in their potential renegotiation? And what sort of timeframe would this be done in?

Existing South Korean tariffs are extremely low and apply exclusively to agricultural goods, ruling out tariff concessions in manufacturing industries. Beyond this, other components, like discussions surrounding the U.S.-Korea security relationship, would also make a Korean deal different than any other deal. This means that there is likely no “one size fits all” solution for countries when reaching an all-in-one trade package.

But Korea seems to have a lot to offer. Already formed commitments, such as Hyundai’s USD 21 billion investment announcement in March and other similar investments, could serve as leverage for a potential investment package, in addition to other new pledges across energy, security, and technology. Indeed, shipbuilding is likely to be a major component of such a deal, where Korea is becoming an increasingly integrated part of the U.S. industry. Seoul has reportedly floated a multi-billion-dollar shipbuilding commitment as a potential component of negotiations, adding weight to other potential partnerships in energy, chipmaking, and factory investment.

All in all, there is still time before the window fully closes on a deal. The pace of negotiations suggests a desire on both sides to get to an agreement. Whatever the outcome, it appears that there will be new rules of the road for U.S.-Korea trade.

Tom Ramage is Economic Policy Analyst at the Korea Economic Institute of America (KEI). The views expressed are the author’s alone.

Feature image from the Japanese Prime Minister’s Office official X account.

KEI is registered under the FARA as an agent of the Korea Institute for International Economic Policy, a public corporation established by the government of the Republic of Korea. Additional information is available at the Department of Justice, Washington, D.C.