The Peninsula

Worrying Trends for the South Korean Won

The South Korean won has reached record lows against the U.S. dollar in recent days, just as heavy U.S. tariffs against what President Donald Trump says is an unsustainable South Korean trade surplus threaten the country’s exports.

The issue, however, is not new. The won—now close to 1,500 to the dollar—was hit hard by the political instability surrounding South Korean President Yoon Suk Yeol’s impeachment and, except for a temporary post-COVID boost, has been on a long slide for more than a decade. Rather than the strong trade surplus strengthening demand for the won and pushing its price up, the opposite has occurred as Koreans have chosen to invest their savings abroad, especially in the United States, rather than at home.

Figure 1: South Korean Won per U.S. Dollar (2016–April 8, 2025)

Source: Trading Economics

The weak won causes all measures of trouble for both the U.S. and South Korean governments. Organizations that receive their earnings in won but must use dollars for their expenses quickly come under strain. Korean students in the United States see their tuition in terms of the won soaring, and Korean tourists are likely to become reluctant to travel abroad. The won-denominated cost of Korean corporate investments in U.S. industries suddenly jumps amid growing questions about the competitiveness of their new U.S.-made products. Dollar-denominated borrowing will need to be repaid with a greater amount of won. Meanwhile, the price of billions of dollars of already ordered U.S. military equipment, such as F-35s, will also jump in terms of their won cost to the country’s already strained budget.

As with many things in economics, this is not all bad. Americans in Korea, or anyone earning their salary in dollars or dollar remittances, are suddenly better off, and U.S. tourism to Korea should soar. Already established Korean auto investments in the United States will gain an advantage over imported cars even though many of their parts are imported from Korea. A stronger dollar cushions U.S. inflation just as it may raise Korea’s, which counteracts some of the much-vaunted tariffs the Trump administration is pushing.

Short-term fears of economic volatility mean that a spiraling effect can emerge wherein people lose confidence in a currency and do not want to hold it, no matter how cheap it gets. A drop in value prompts further declines rather than a rebound. Interest rates soar, investments collapse, and a negative growth cycle turns into an economic depression.

Political Trouble

An economic depression is unlikely, but the current economic crisis is real. It is hard to ignore the political and diplomatic dangers presented by a weakened won for Seoul. The cheaper won is making Korean exports to the United States less expensive while raising the price of imported goods, especially energy and food items, which causes Korea’s trade surplus to rise to near-record levels. Trump is concerned with the global rise in the U.S. trade deficit, reaching an all-time high in January, and wants to use tariffs to try to reduce it. Korea is not a small player in the U.S. deficits, as noticed in Trump’s address to Congress.

For the United States, tariffs can help reduce both the foreign deficit and the federal government’s huge fiscal deficit and are thus politically appealing. But they cause trouble for Korean companies that have promised big U.S. investments, and the Korean government must deal with complaints of higher imported oil, gas, and food prices. There are also always questions of “currency manipulation.” Those with a limited understanding of financial flows will see Seoul as manipulating its reserves and monetary policy to artificially lower its currency, giving a boost to export-led growth at the expense of U.S. industries.

We can discount the idea of currency manipulation—millions of people freely buying and selling a currency that is openly traded can hardly be accused of manipulation. Nonetheless, Seoul’s monetary authorities are in a bind, trying to carefully balance their desire to lower interest rates to encourage domestic investment and GDP growth while needing to raise rates to protect the currency.

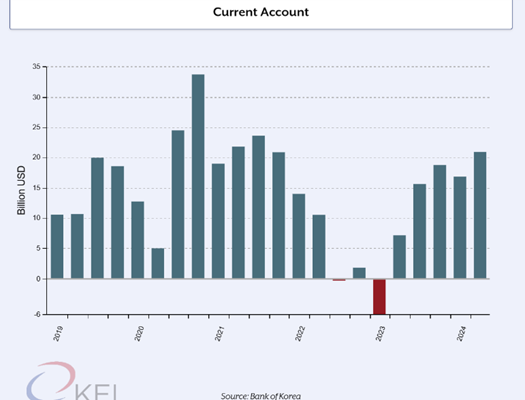

Figure 2: South Korea Current Account (2016–2024)

At first glance, the won’s weakness does not seem to make economic sense. Korea is running a high trade and current account surplus, so dollars are pouring into the country. A surplus of dollars should make them less valuable, and the won should rise in value. Korean inflation, at about 2 percent per year, is lower than that of the United States, with about 2.8 percent.

A Simple Balance Sheet Calculation

There are similarities between the current Korean economy and the Japanese economy three decades ago when it shifted from a high-growth, investment-led economy to decades of slow growth, anemic domestic investment, and little or no inflation—all while the yen declined persistently. These warnings are shown in financial and national income account data from the Bank of Korea (BOK), the opposite side of the ledger of the trade or current account, for 2024. In the accounting, which is used to calculate GDP and economic growth, a positive and growing current or trade account—USD 99 billion for the year—is matched by a USD 94 billion increase in purchases of foreign assets. Thus, the dollars earned by exporting do not disappear or circulate inside South Korea but are lent back to the United States and other countries in a reverse flow.

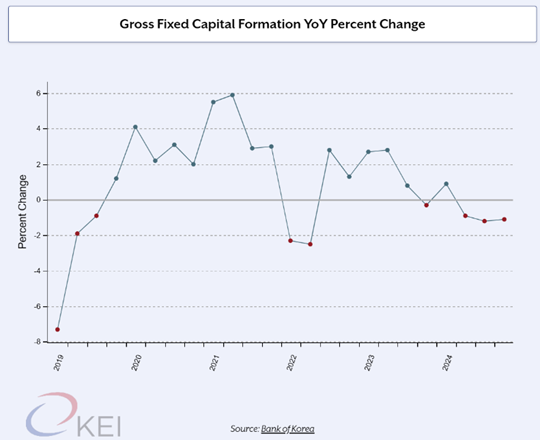

Figure 3: South Korea’s Gross Fixed Capital Formation Year-on-Year Change

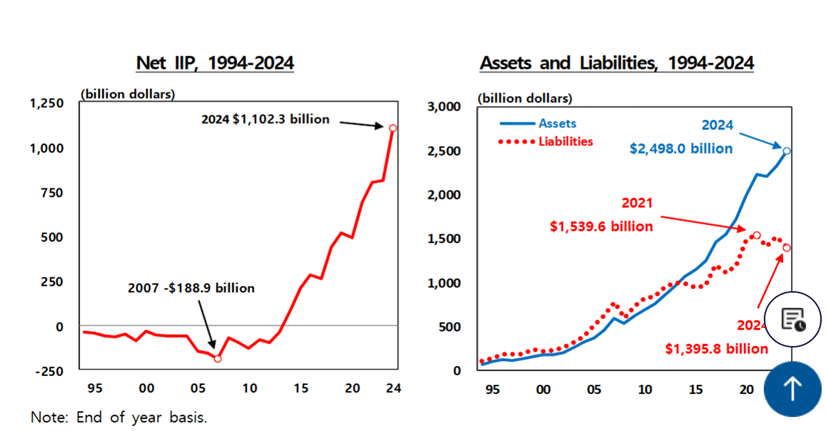

In other words, from a zero balance ten years ago, South Korea now has USD 1.102 trillion in net foreign assets. Assets (Korean-owned investments abroad) of USD 2.498 trillion are only partially offset by USD 1.395 trillion in liabilities (foreign-owned investments in Korea.)

On the other side of the coin, after decades of negative trade balances, the United States now has a huge stock of foreign debt—an issue that Trump has vowed to correct. There seems to be no limit on the U.S. ability to borrow, so lenders keep accepting U.S. money. The United States has proven to have the best, most liquid, and most protected capital markets and is thus a haven for foreign savings, especially when global instability reigns.

Figure 4: South Korea Net International Investment Position and Assets and Liabilities (1994–2024)

Source: Bank of Korea | Note: End-of-year basis. Net position refers to the cumulative additions minus sales of foreign assets over the decades. Assets are Korean-owned assets abroad, and liabilities are foreign-owned assets in Korea.

South Korea Fixed Investment From 2016 to 2024

For Korea, such a surplus seems beneficial. It added USD 28.6 billion in interest and profits to its foreign assets in 2024, adding to national income and GNP. This can be positive because the country will need to draw on these savings as the population ages. Production and exports (GDP) may falter or grow slowly, and imports will stream in, paid for by income from their foreign assets, which is what has happened with Japan in the 1990s.

BOK data shows trends that are in line with Japan’s recent economic history. GDP growth is weak, reaching only 1.1 percent in the fourth quarter year-on-year, which is about half the growth rate of the U.S. economy. Consumption expanded modestly, but investment, shown in the graph as gross capital fixed capital formation, plunged. Savings are sufficient, but the money is flowing overseas, predominately invested in U.S. assets and not domestically. The central bank has tried to lower interest rates to encourage domestic investments but is stymied because doing so would knock the won down further. Expectations that the BOK is stuck, unable to protect the won by raising rates or lowering them to induce investment, are distressing financial markets and creating further duress for the system.

A Win-Win Solution

Both South Korea and Japan owe their incredible economic development to policies that encouraged domestic savings. Their well-formed financial institutions and corporations took these savings and invested them productively at home and abroad. But in doing so, they limited the inflow of foreign investment.

The South Korean government should induce more U.S. investment, which would lead to greater competition among foreign investors in Korea. This would raise demand for the won and Korean imports, thus reducing the big current account surplus. Investments in Korea would increase, balancing the surplus and inducing more growth. Investing abroad would continue, but a more balanced approach might pay great dividends for both Washington and Seoul.

William B. Brown is Distinguished Fellow at the Korea Economic Institute of America and the principal of Northeast Asia Economics and Intelligence, Advisory LLC (NAEIA.com). The views expressed here are the author’s alone.

Photo from Shutterstock.

KEI is registered under FARA as an agent of the Korea Institute for International Economic Policy, a public corporation established by the government of the Republic of Korea. Additional information is available at the Department of Justice, Washington, D.C.