The Peninsula

Will Shifting Economies Aid Trump’s North Korea Gambit?

Published November 9, 2018

Category: South Korea

By William B. Brown

Presidents Xi Jinping and Moon Jae-In might like to shift public attention away from economics as they travel to the G-20 talks in Argentina later this month, given last week’s not so great third quarter GDP releases. North Korea’s continuing charm offensive is a likely positive, confidence building alternative for them, even if U.S.-led de-nuclearization talks remain jammed. And Prime Minister Shinzo Abe may be struggling to find good news as well after Japan’s third quarter GDP is announced November 14th. This all in contrast to accelerating U.S. growth and President Trump’s “the best U.S. economy, ever” proclamations. But can Trump use this economic strength to keep China and South Korea in line with his delicate task of negotiating North Korean de-nuclearization while maintaining tough sanction pressures? The issues are invariably complicated, but Trump may be gaining leverage as other Asian leaders become ever more dependent on U.S. economic and trade policies to stay above water. Simply a phone call between Trump and Xi last Thursday, followed by mildly positive Trump remarks, is said to have caused the 3 percent jump in China’s beleaguered stock prices. Much will ride on the Xi-Trump dinner conversation in Buenos Aires at the end of the month where presumably the “trade war” and North Korea sanctions will be addressed. One might think Xi will be more concerned with the former than the latter, and pressures on North Korea will be maintained.

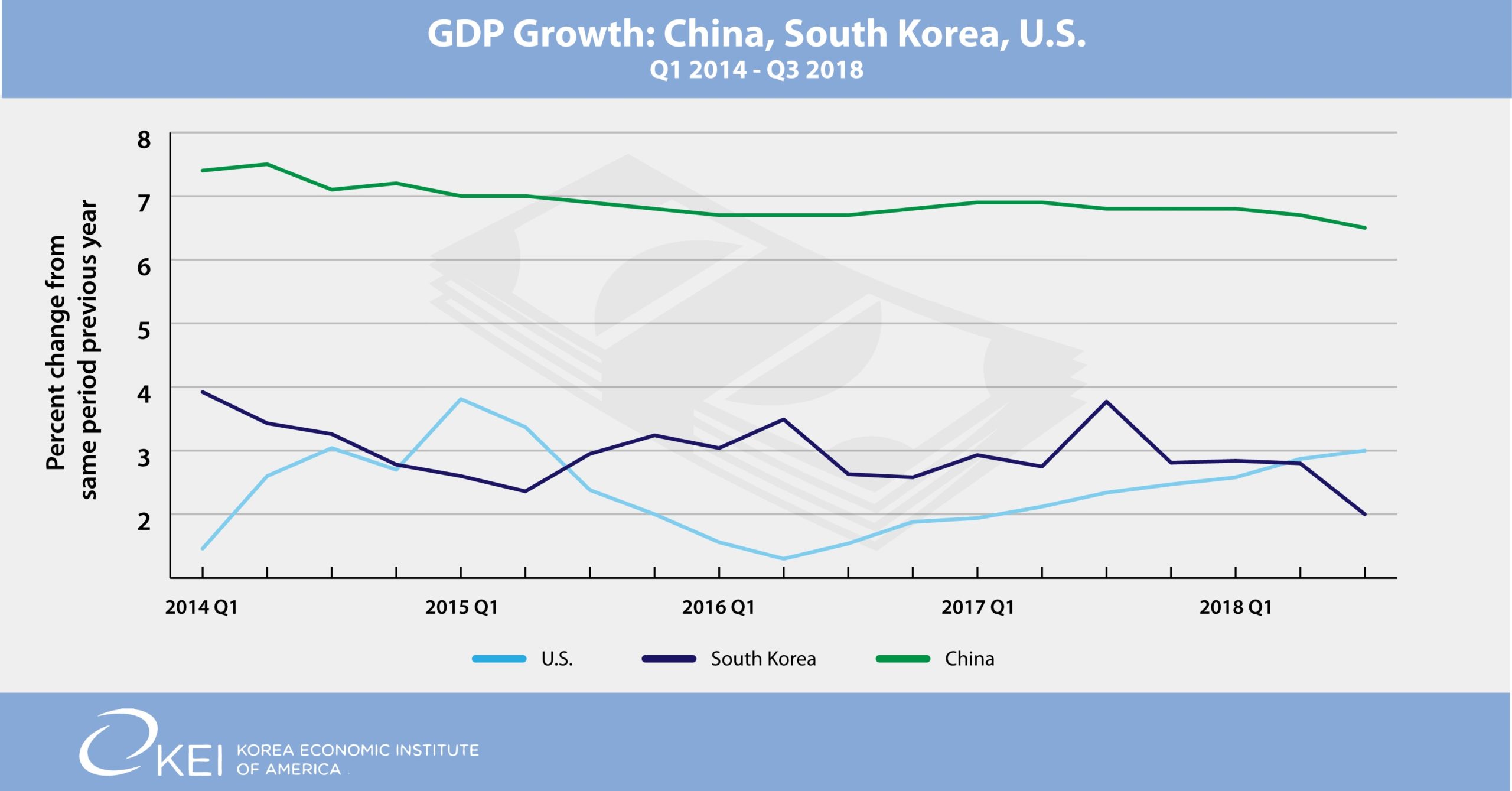

The third quarter data was not alarming for East Asia, especially as seen from the stabilized year-on-year perspective, but important trends appear to have set in that favor U.S. strength, with U.S. demand supporting rest-of-the-world growth. U.S. GDP slightly exceeded expectations with growth at 3.0 percent from the same quarter of 2017, higher than South Korea’s disappointing 2.0 percent—a rare quarter in which the U.S. has grown faster than Korea.And it came despite a large negative contribution from net exports as surging imports pushed the U.S. trade deficit to record levels. China’s growth was more than double that, at 6.5 percent, but is steadily slowing from pre-Xi Jinping boom years, a fact not lost on a Chinese public used to much more rapid gains. Japan will release its data November 14th and is expected to record negligible or even negative growth.

More volatile quarter-to-quarter data gives similar results, with the U.S. showing 3.5 percent seasonally adjusted annualized growth in the third quarter; South Korea about 2.5 percent (.6 percent q/q) and China close to a steady 6.5 percent (1.6 percent q/q).

South Korea’s third quarter performance only barely missed expectations of 2.2 percent growth from third quarter 2017, but the components are more disappointing. Growth was boosted by a decline in imports, especially of factory equipment, and a big rise in government spending. Exports were strong, despite all the talk of trade tensions with China and the U.S., its first and second largest markets. But facility investment and construction fell at the fastest rates since the global recession a decade ago, adding to big declines in the second quarter. Private consumption maintained steady 2 percent growth despite growing household indebtedness. Employment is weak and confidence in the economy seems to be slipping, a big determinant of future growth.

China’s GDP also slightly missed expectations in the third quarter, registering 6.5 percent instead of 6.6 percent growth from year-earlier levels, the slowest rate in a decade. As with South Korea, net trade, especially exports to the U.S., added substantially to growth while investment spending grew much more slowly than in the past. The impact of the “trade war” so far has not so much impacted Chinese exports—there may be some front loading ahead of U.S. tariff bites later in the year—but rather seems to be dealing a blow to investor confidence. Middle class consumer confidence also is off as worries about trade wars intensify, according to analysis by the South China Morning Post. Since talk of U.S. tariffs began last spring, the yuan has dropped against the dollar by nearly ten percent, offsetting to a large extent the announced, average U.S. tariff increases. Stock index averages also are off about ten percent over the same six months.

Japan’s GDP surged in the second quarter but is widely expected to have shown zero or negative growth in the third, and like its East Asian partners, a victim of lost investor confidence and high dependency on exports to the United States. Given the strains, all three East Asian leaders will need to improve public confidence in their leadership skills if investment spending is to recover enough to avoid real trouble. Getting in line with Trump on trade policies at the G-20 may be difficult but staying in line on North Korea might be a good way to start.

William Brown is an Adjunct Professor at the Georgetown University School of Foreign Service, a Non-Resident Fellow at the Korea Economic Institute of America, and the Principal at Northeast Asia Economics and Intelligence Advisory, LLC (NAEIA.com). The views expressed here are the author’s alone.

Photo from Jason’s photostream on flickr Creative Commons.