The Peninsula

What Would a Modern Greek Euro Tragedy Mean for Korea?

By Troy Stangarone

For Greece, tragedy has become a well worn tradition. Whether at the pen of ancient writers such as Sophocles or civil war during and after the Second World War, Greece is well versed in the causes and consequences of tragedies even if they have rarely touched directly on other nations. However, unlike past Greek tragedies the current euro crisis has the potential to have significantly wider consequences for both Europe and more distant nations like Korea.

As Greece heads towards a second election in little less than a month on June 17 after having failed to form a government following an inclusive vote on May 6, a Greek exit (Grexit) from the euro has become an increasingly real possibility. Ordinarily a default by a country the size of Greece would have minimal impact on the broader global economy and financial system, but because of Greece’s place in the euro its exit could have broader reaching consequences.

The Challenges in Greece

Greece currently faces political paralysis in addition to its economic woes. While strong majorities support remaining in the euro, they have also become weary of the punishing austerity that has become the price for remaining. The economy has not grown since 2007 and unemployment is currently more than 20 percent, surpassed only by Spain among countries in Europe. At the same time, the political parties have not risen to the task of leading the nation. Transcripts of recent talks to form a unity government reveal little discussion of key issues such as how to keep Greece in the euro despite strong 80 percent public support for remaining in the currency union.

Some of the paralysis is likely tied to the political objectives of the parties involved. In order to secure the most recent bailout funds, all of the parties in government at the time had to pledge their support for the terms of the bailout, including the traditional parties of New Democracy and Pasok. This allowed Syriza, a relatively new left wing coalition lead by Alexis Tsipras, to campaign on the platform of repudiating the terms of the bailout and to secure a second place finish in the May 6 elections. Current polling has Syriza expected to win the new poll and would likely seek some renegotiation of the deal if it were able to form a government. Should the next government in Athens repudiate the existing bailout arrangements, Greece’s creditors – the EU and the IMF – would likely cut off its funds. The probable result would be to force Greece from the euro zone.

At the same time, the choice of exit could quickly move beyond the control of the politicians. Since 2009, Greeks have been withdrawing deposits from banks at a rate of about 2-3 billion euros a month. That increased to 700 million euros on May 14 alone when it became clear that new elections would be needed and departure from the euro became a real possibility. As of March, there were still 165.36 billion euros in Greek banks. Should fears heighten that a Greek exit from the euro were eminent, Greece’s slow bank run could speed and drain the system of euros forcing its exit from the common currency.

The Challenges in Europe

The current crisis in Greece is one that is both a creature of Greek creation and a failure of Europe to decisively address Greece’s debt crisis from the beginning. Rather than take decisive action to shore up Greece and restore confidence to markets that Greece’s debts would be honored, Europe has taken an incremental approach to addressing the crisis that has allowed contagion to spread to systemically important countries in the euro zone such as Spain and Italy.

One of the challenges that Europe faces is that, as Martin Wolf of the Financial Times and others have noted, European leaders have a fundamental misunderstanding of the causes of the crisis. While much of the focus has been on debt levels and spendthrift governments, that does not accurately reflect the facts prior to the crisis when Ireland and Spain both had significantly lower levels of net public debt than Germany. Portugal, another country caught by contagion had a debt to GDP ratio of 64 percent, in comparison to Germany’s 50 percent, while Italy has long functioned on high levels of public debt. Greece is the one case where the level of debt was truly an issue.

Rather than the level of public debt, Wolf has suggested that the true indicator of which countries were vulnerable to the crisis were those who faced current account outflows in the lead up to the global financial crisis. Much of the imbalance that has developed internally within the eurozone reflects the changes in competitiveness that have occurred under the euro and the inability of those countries that lost competitiveness to devalue their currency to adjust.

This raises questions about the focus on fiscal austerity that Europe has pursued, and Germany has steadfastly insisted on, as a cure for the crisis. While the debt accumulated by countries like Ireland and Spain as a result of the crisis has to be addressed, without policies that spur growth the crisis will at a minimum continue if not worsen.

Greece specifically, but others as well have found themselves caught in a debt trap where cuts to spending weaken the economy, reducing the government’s ability to pay its debt. This in turn leads to further cuts to address debt, which again weakens the economy. As we have seen in Greece, and to an extent in Spain, this is not a politically feasible option in the long-term. Only economic growth that provides these countries hope of reducing unemployment and growing out of their debts will work in the long run.

Much like Greece, the EU also faces its own political crisis. With the crisis in Greece continuing to grow, divisions have begun to emerge among European leaders about how best to address the crisis. At a recent summit meeting in Brussels, leaders were unable to come to a consensus on basic steps to promote growth in the euro area, let alone more robust solutions such as the introduction of euro bonds backed by all of the member states. This, despite new evidence of an economic slowdown in Europe that could further undermine the EU’s ability to address the crisis.

The Potential Impact on Korea

Countries beyond Europe, like Korea, are already being impacted by the potential exit of Greece from the euro with a series of Asian currencies dropping to five month lows and $1.1 billion recently being withdrawn from equity markets in Korea, Taiwan, Thailand, and Indonesia. However, in trying to answer what a Greek exit from the euro would mean for Korea, it largely depends on the unknown factor of whether the crisis could be contained or would spread beyond Greece itself.

The current concern is that once Greece leaves the euro, what was once considered an irrevocable currency union will be broken and markets will drive the borrowing rates of Italy and Spain to unsustainable level forcing them out of the euro as well, setting off another global financial crisis similar to what occurred after the collapse of Lehman Brothers in 2008. However, if Europe were able to put in place the appropriate firewalls because Greece is on the periphery of the global economy, rather than central to it, the crisis would largely only be felt in southern Europe and to a lesser degree in northern Europe.

While the extent of the crisis may be unknowable, we do know what the potential areas of impact on Korea would be. If a Greek exit from the euro were to set off a financial crisis, Korea would likely experience financial outflows and depreciation in the value of the won similar to what occurred in 2008. This would likely be manageable for Korea and it has already begun to take steps to address the potential financial fallout of the crisis in Greece. When the financial crisis of 2008 hit, Korea took decisive actions based on the lessons learned from its experience in the Asian Financial Crisis of 1997. It is likely that the Korean government would again move decisively to address the any challenges stemming from a Greek exit of the euro zone.

However, the Korean economy is highly dependent upon trade, and this could be the larger concern from a Korean perspective. Europe represents about 10 percent of Korea’s trade and is one Korea’s four largest trading partners. A recent report by the Hyundai Research Institute indicates that if Europe’s imports fall by 20 percent, Korea’s exports would drop $12.8 billion, while a 30 percent reduction could result in a decrease of $20.7 billion.

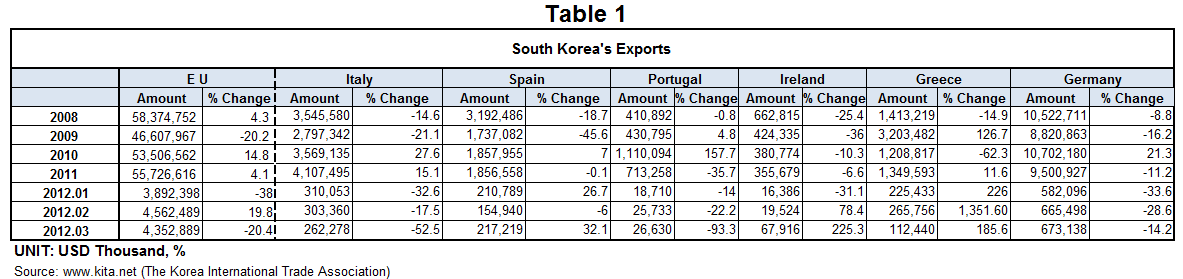

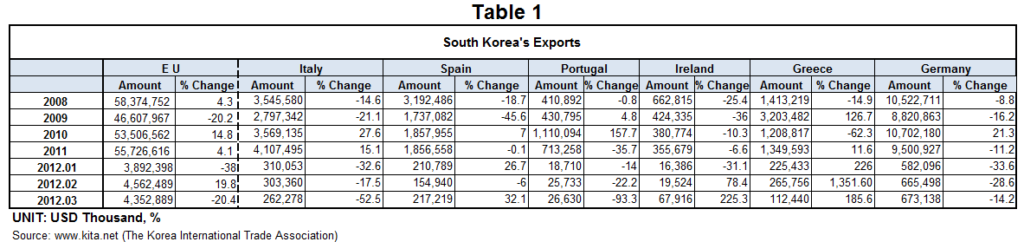

We can already see reductions in exports to the EU taking place. As seen in Table 1, in the first three months of this year exports to the EU are were down by 38 percent in January and 20 percent in March from the same months in 2011. While it is not surprising that exports to Greece, Italy, Spain and other countries caught up in the euro crisis are down, even exports to Germany which has been the strongest economy in the euro zone are down 14 percent in March. In 2009, when the global financial crisis was at its height, Korea’s exports to the EU were down by 20 percent. Though, perhaps in a strange twist, Korean exports to Greece were up significantly that year.

Beyond Korea’s prospects in European markets, if Greece were to precipitate a new financial crisis the challenges for the global economy could be more significant than they were in 2008-2009. With China’s economy slowing and the United States and Europe having seen significant spikes in debt since 2008, there will be less leeway for expansionary economic policies that might soften any downturn. In turn, Korea would likely experience a softening of its export prospects in its other major export markets in China, Japan, and the United States.

While no one can predict how markets would truly react to a Greek exit from the euro and the carry-on contagion effects, the experience of 2008 shows that if the crisis were to spread beyond Greece itself there would likely be a significant impact on Korea. This prospect alone makes the modern day tragedy unfolding in Greece worth bearing in mind.

Troy Stangarone is the Senior Director for Congressional Affairs and Trade for the Korea Economic Institute. The views expressed here are his own.

Photo from Sotiris Farmakidis’ photo stream on flickr Creative Commons.