The Peninsula

What to Make of North Korea's Fastest Economic Growth Since 2016

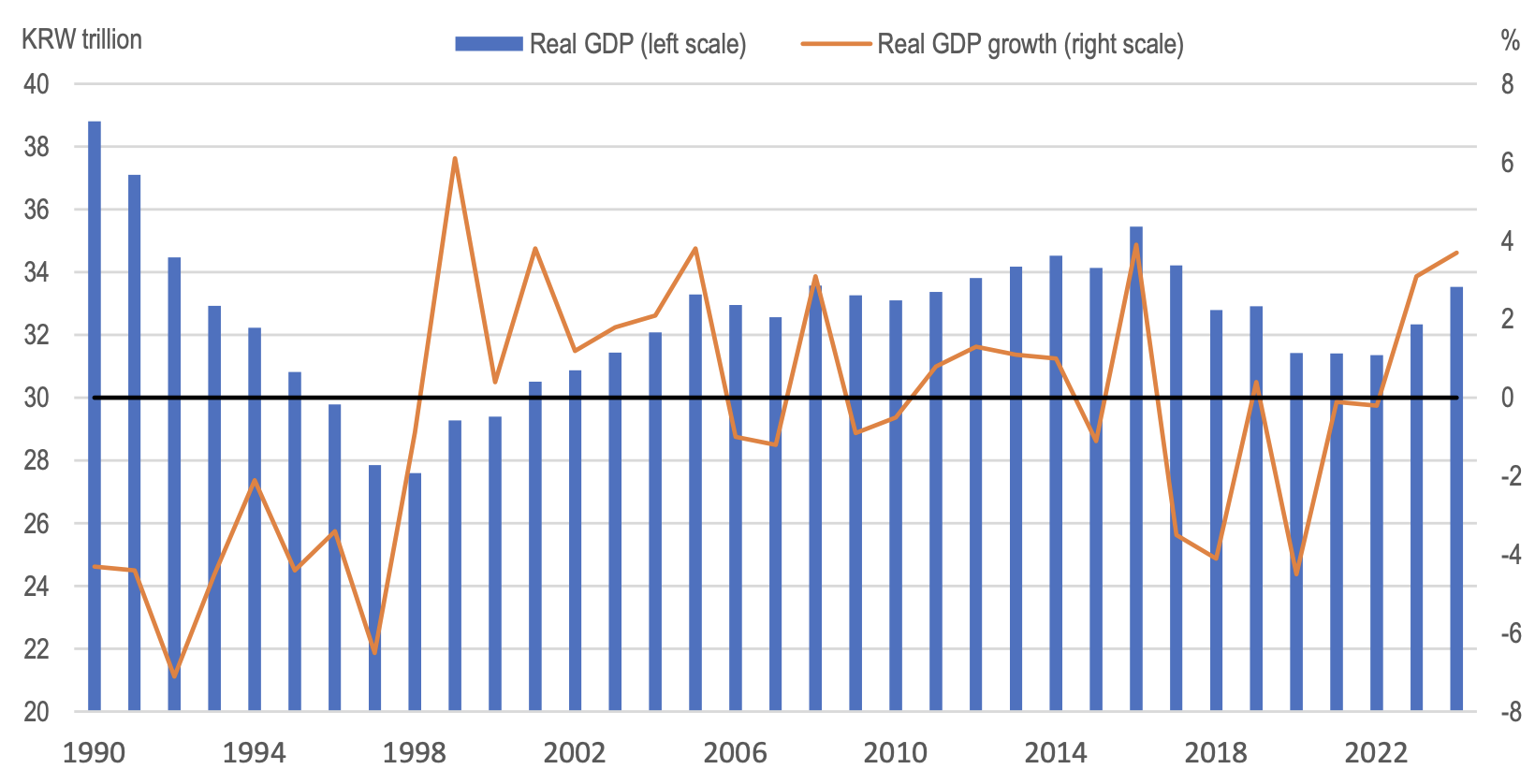

The North Korean economy grew 3.7 percent in 2024 (Figure 1), its fastest pace since 2016, according to estimates by South Korea’s central bank announced at the end of August. North Korea’s second straight year of positive growth propelled its GDP to its highest level since 2017, reversing the declines driven in part by international sanctions and the closing of its borders during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Figure 1. North Korea’s economy grew an estimated 3.7 per cent in 2024, the fastest pace in eight years

Source: Bank of Korea

Estimates of economic developments in North Korea should be taken with a grain of salt. The country has not published regular national account statistics since the 1960s, nor any budget information in level terms since the early 1980s. The Bank of Korea (BOK) bases its estimates on information from a range of sources, including intelligence and foreign trading agencies, as well as data from South Korea’s Ministry of Unification. Some North Korea experts argue that the BOK’s estimates are too optimistic, but there are few alternatives so long as the Kim Jong Un regime maintains such severe secrecy.

Domestic Projects and Increased Cooperation and Trade with Russia Drove North Korean Growth

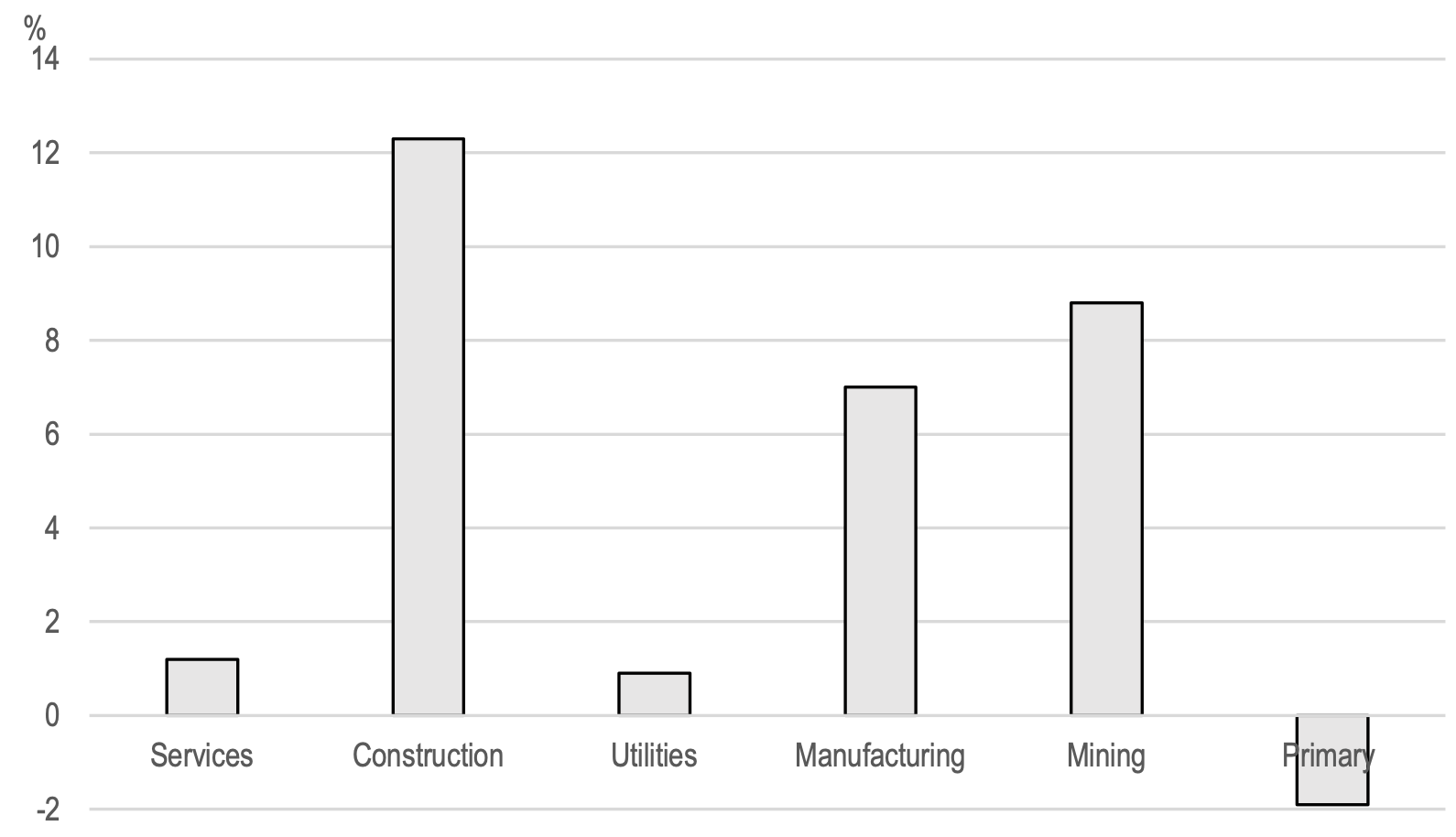

The Bank of Korea attributed the increase in North Korea’s GDP in 2024 to “significant increases in manufacturing, construction and mining industries, which were affected by the strengthening of national policy projects domestically.” In January 2024, Kim Jong Un launched the “Regional Development 20×10 Policy” to narrow the gap between Pyongyang and the rest of the country. This initiative aims to create “modernized factories” in 20 cities and counties per year over the next 10 years. The government has mobilized the army to implement the 20×10 Policy. Given that North includes approximately 200 cities and counties, this initiative aims at a comprehensive transformation of local economies over the next decade. These projects may have helped sustain manufacturing and construction, which accounted for two-thirds of GDP growth in 2024 (Figure 2). However, the government’s focus on military and nuclear weapons development may limit its financial capability to achieve its regional development objectives.

Figure 2. North Korea’s growth in 2024 was driven primarily by manufacturing and construction

Note: Utilities include electricity, gas and water supply. Primary industry includes agriculture, forestry and fishing. | Source: Bank of Korea

The central bank also cited the “expansion of economic cooperation between North Korea and Russia” as an external factor contributing to stronger growth. The June 2024 treaty between the two countries committed them to mutual military aid and strengthened their military ties. North Korea’s production of metal products increased sharply to supply weapons to Russia, boosting output in the heavy and chemical industry sector by 10.7 percent, the highest rate since the BOK began estimating North Korean GDP in 1991.

The Per Capita Income Gap Between North and South Korea Remains Large

South Korea’s growth of 2.0 percent in 2024 lagged behind the BOK’s estimate for the North. Consequently, the gap in gross national income (GNI) narrowed slightly, though the South’s GNI was 58.4 times higher than that in the North (Table 1). Given that South Korea’s population is twice that of the North, its per capita GNI is estimated to be about 29 times larger, up from 22 times in 2016.

The gap in international trade in 2024 was even larger, with the South’s combined exports and imports nearly 500 times greater than North Korea’s. Despite doubling in 2022 and increasing further in 2024, North Korean exports totaled only USD 0.36 billion, reflecting its economic strategy and the difficulty in trading with the country. The main export increases were in items such as hats, wigs, as well as ore, slag and ash. Although North Korean imports declined in 2024, its trade deficit remains significant, raising questions about how such a large imbalance can be financed. There was no trade between North and South Korea in 2023 and 2024.

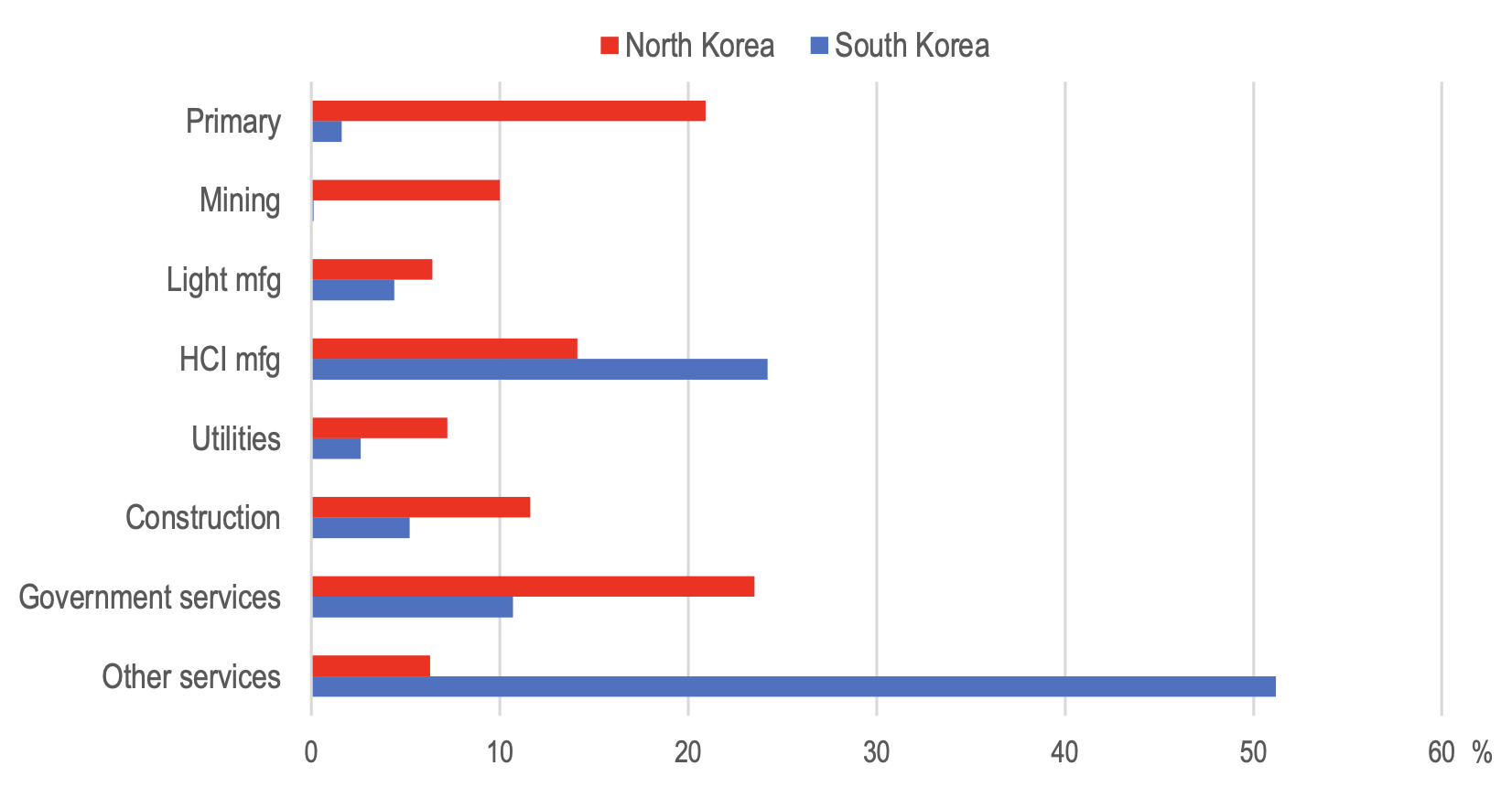

The BOK estimates also indicate sharp differences in the industrial structure in the two Koreas (Figure 3). First, primary industry (agriculture, forestry and fishing) accounted for more than 20 percent of North Korean GDP compared to only 1.6 percent in the South. Second, mining is a significant sector in the North, accounting for 10 percent of GDP, whereas it was negligible in the South. Third, heavy and chemical industry manufacturing accounted for 24 percent of South Korean GDP, 10 percentage points more than in the North, where light manufacturing’s share of GDP exceeds that in the South. Fourth, the share of construction, at 11.6 percent, in the North is twice that in the South. Fifth, government services’ share of GDP in the North is about double that in the South. However, other services, which account for more than half of South Korean GDP, play only a minor role in the North.

Table 1. Comparison of North and South Korea in 2024

| North Korea (A) | South Korea (B) | Ratio (B/A) | ||||

| 2023 | 2024 | 2023 | 2024 | 2023 | 2024 | |

| Population (thousands) | 25,709 | 25,816 | 51,713 | 51,751 | 2.0 | 2.0 |

| Nominal GNI1 (KRW trillion) | 40.9 | 44.4 | 2,443.4 | 2,593.8 | 59.8 | 58.4 |

| Per capita GNI1 (KRW million) | 1.589 | 1.719 | 47.249 | 50.120 | 29.7 | 29.2 |

| Exports (USD billion) | 0.33 | 0.36 | 632.23 | 683.61 | 1,944.3 | 1896.6 |

| Imports (USD billion) | 2.44 | 2.34 | 642.57 | 631.77 | 262.9 | 270.5 |

| Total trade (USD billion) | 2.77 | 2.70 | 1,274.80 | 1,3153.80 | 460.4 | 487.9 |

- GNI is Gross National Income | Source: Bank of Korea

Figure 3. The industrial structures of North and South Korea differ considerably

Note: Utilities includes electricity, gas and water supply. Primary industry includes agriculture, forestry and fishing. HCI refers to heavy and chemical industries. Other services refer to: i) wholesale & retail trade, accommodation & food services; ii) transportation & communications; and (iii) finance, insurance & real estate. | Source: Bank of Korea

Conclusion

The enormous income gaps between the two Koreas have long raised concerns that North Korea is a contingent liability that could impose a huge fiscal cost on South Korea in the case of unification. However, the prospects for unification appear remote, especially given that economic cooperation on the Korean peninsula has ended. In December 2023, Kim Jung Un stated that North-South relations had entered a hostile state of war between the two countries. In January 2024, he designated South Korea as the North’s “principal enemy” and requested the deletion of the text in North Korea’s constitution promoting peaceful unification. State agencies dedicated to unification and inter-Korean tourism were closed.

Economic reform to achieve faster growth in North Korea remains essential to address its ongoing humanitarian crisis. The United Nations’ World Food Program has estimated that 10.7 million North Koreans (40 percent of the population) are undernourished. While North Korea’s economic growth has turned positive, it faces the challenge of reducing hunger and food insecurity, as well as achieving its regional development objectives.

The sharp depreciation of the North Korean won is exacerbating food insecurity. The currency reportedly surpassed 40,000 won per dollar in August 2025 from around 8,000 won at the end of the COVID-19 pandemic. The currency decline has led to significant increases in the prices of basic commodities. According to one estimate, the prices of rice and corn, which were relatively stable at around 4,000 won and 2,000 won per kilogram, respectively, during the past decade, have surged to 20,000 won and 6,000 won per kilogram. Reducing North Korea’s high level of military expenditure would facilitate policies to improve the standard of living for its citizens.

Randall S. Jones is Distinguished Fellow at the Korea Economic Institute of America. The views expressed here are the author’s alone.

Photo from North Korean state media.

KEI is registered under the FARA as an agent of the Korea Institute for International Economic Policy, a public corporation established by the government of the Republic of Korea. Additional information is available at the Department of Justice, Washington, D.C.