The Peninsula

Unpacking the Underlying Trends of South Korean Trade from July

South Korean media coverage surrounding the latest monthly trade data released by the government struck a positive tone regarding the overall trajectory of the Korean economy, which experienced a significant increase in semiconductor and automotive exports. Trade has an outsized role in the South Korean economy—total trade relative to South Korean GDP was approximately 90 percent in 2023. Thus, it is worth reviewing the latest numbers for South Korean trade and its relationships with its largest trading partners while considering the drivers behind the trends.

South Korea’s Sustained Trade Surplus

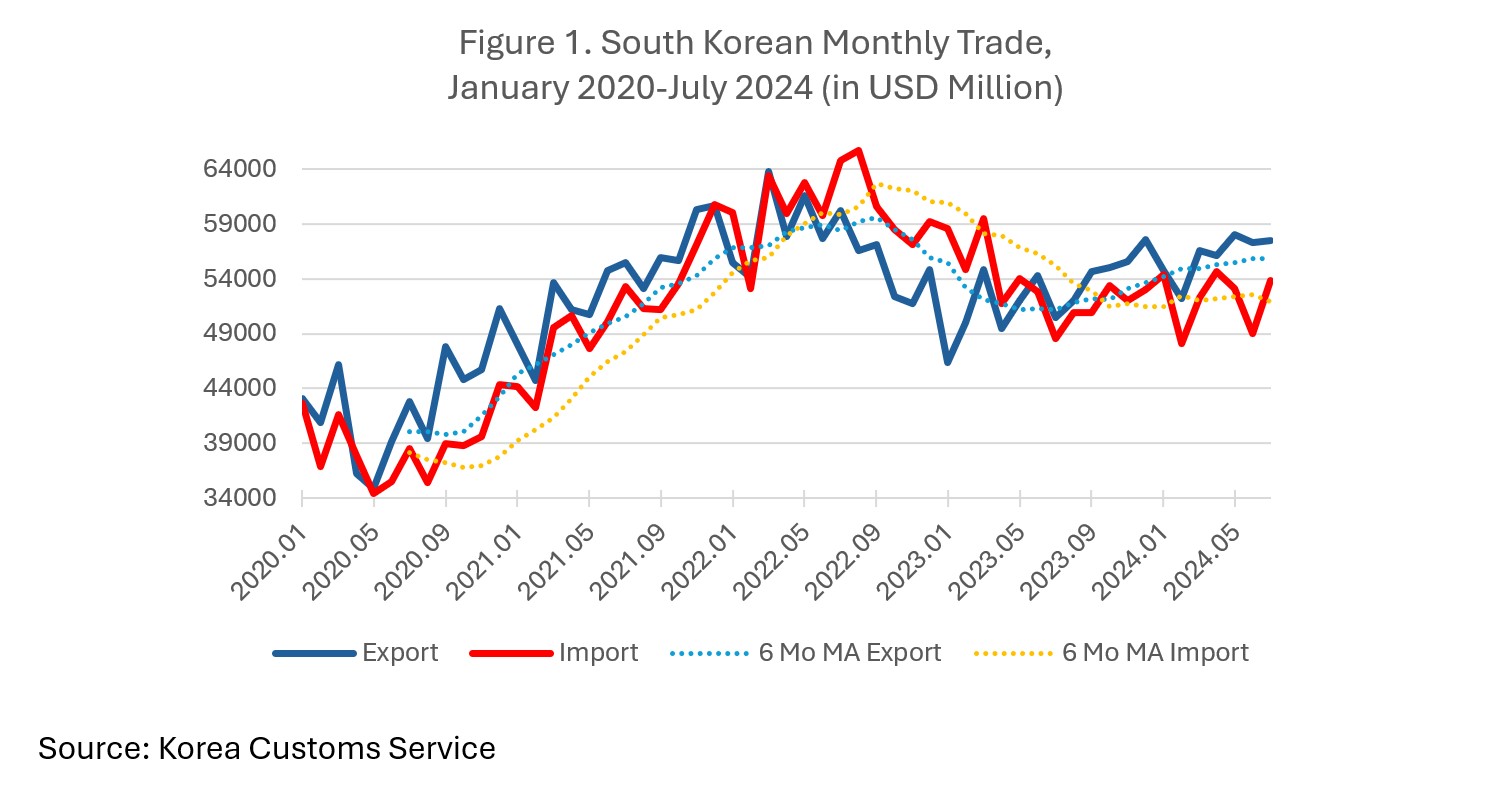

July’s trade data showed that South Korean exports remained strong at roughly $57.5 billion, which is slightly lower than in June (roughly $57.4 billion) but 5 percent higher than the beginning of the year ($54.8 billion in January). Imports also bounced back from $49 billion in June to $53.8 billion in July, but the year-to-date (YTD) growth decreased by 1 percent (Figure 1).

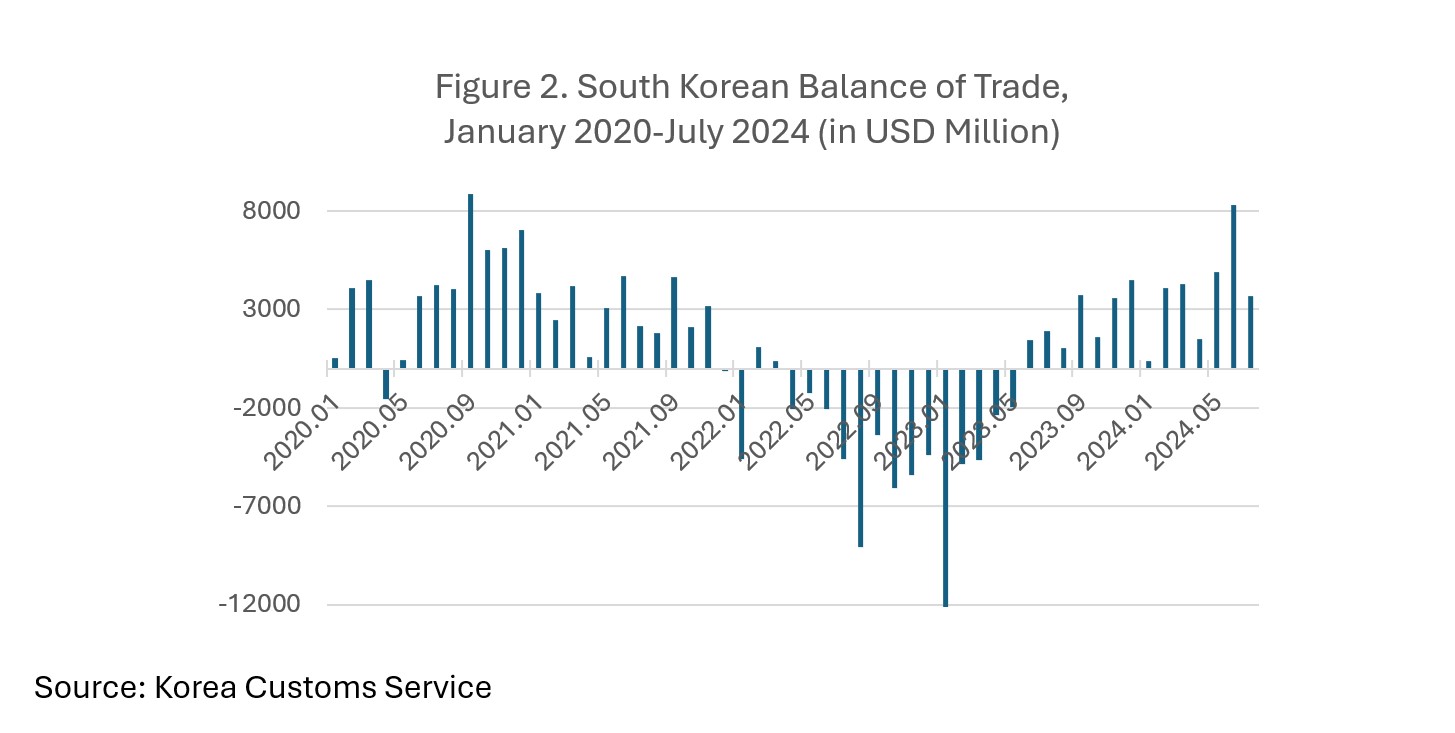

These numbers are reinforced by South Korea’s sustained positive trade balance that can be attributed to a combination of factors starting in the middle of 2023, which is discussed in greater detail below (Figure 2).

The Tale of Two Trades

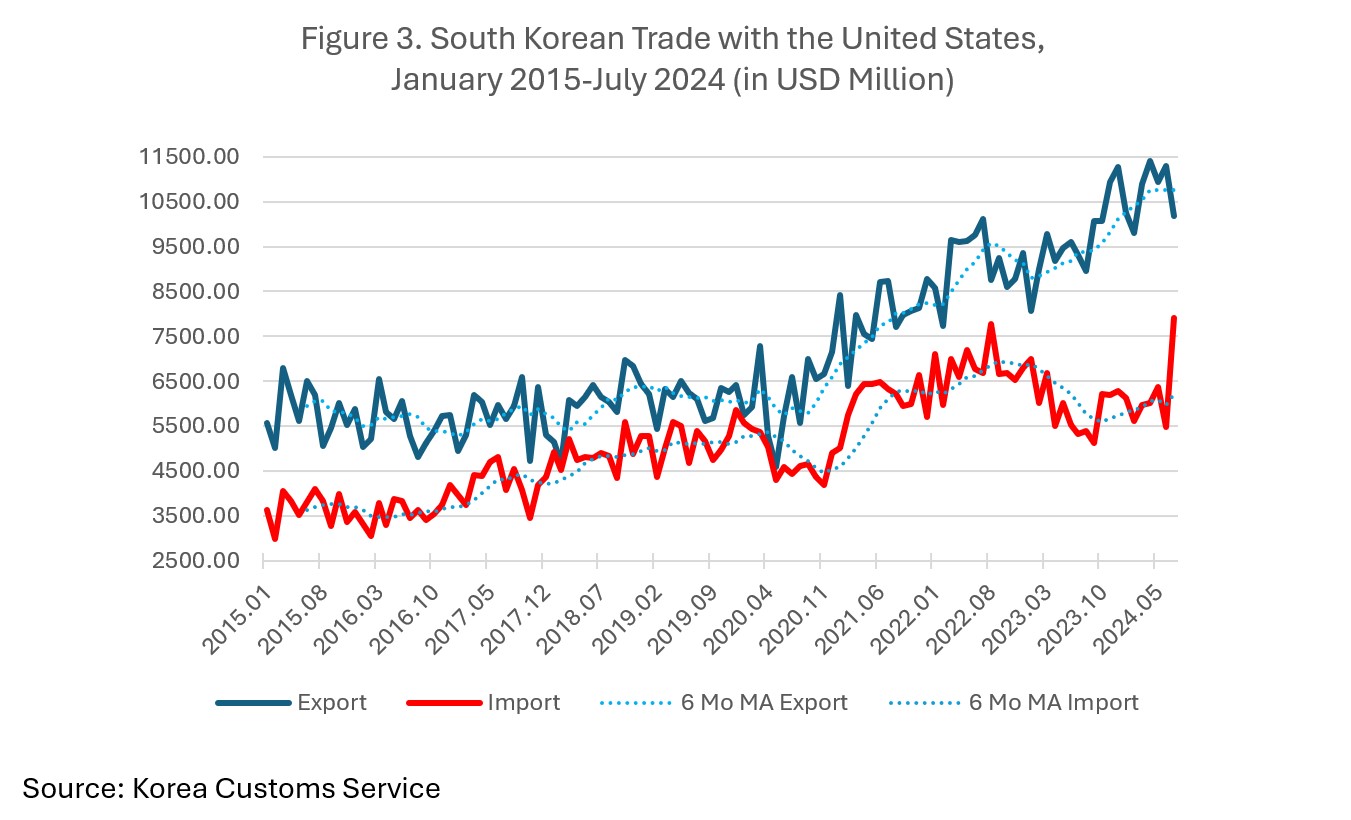

One noticeable change in South Korea’s economic landscape appears to be a more vibrant trade relationship with the United States. The data shows that Korean exports to the United States grew by 9.3 percent from $9.3 billion in January 2020 to over $10.2 billion in July 2024 (Figure 3). Imports also grew by nearly 49 percent from $5.3 billion to $7.9 billion during the same period, helped by a big jump just this last month. Much of this gain came from two sources: crude oil (HS 2709) and aircraft (HS 8802). Crude imports to South Korea increased from $6.6 billion in June to $7.2 billion in July. Similarly, imports of aircraft amounted to $1.1 billion, which was a 78 percent increase from June ($237 million).

This fits into the overall trade trend of the United States, in which the total amount of imports went from $315.87 billion in January 2022 to $339 billion in June 2024, an increase of 7.3 percent. Meanwhile, US exports during the same period grew from $251 billion to $265.9 billion, an increase of 5.9 percent.

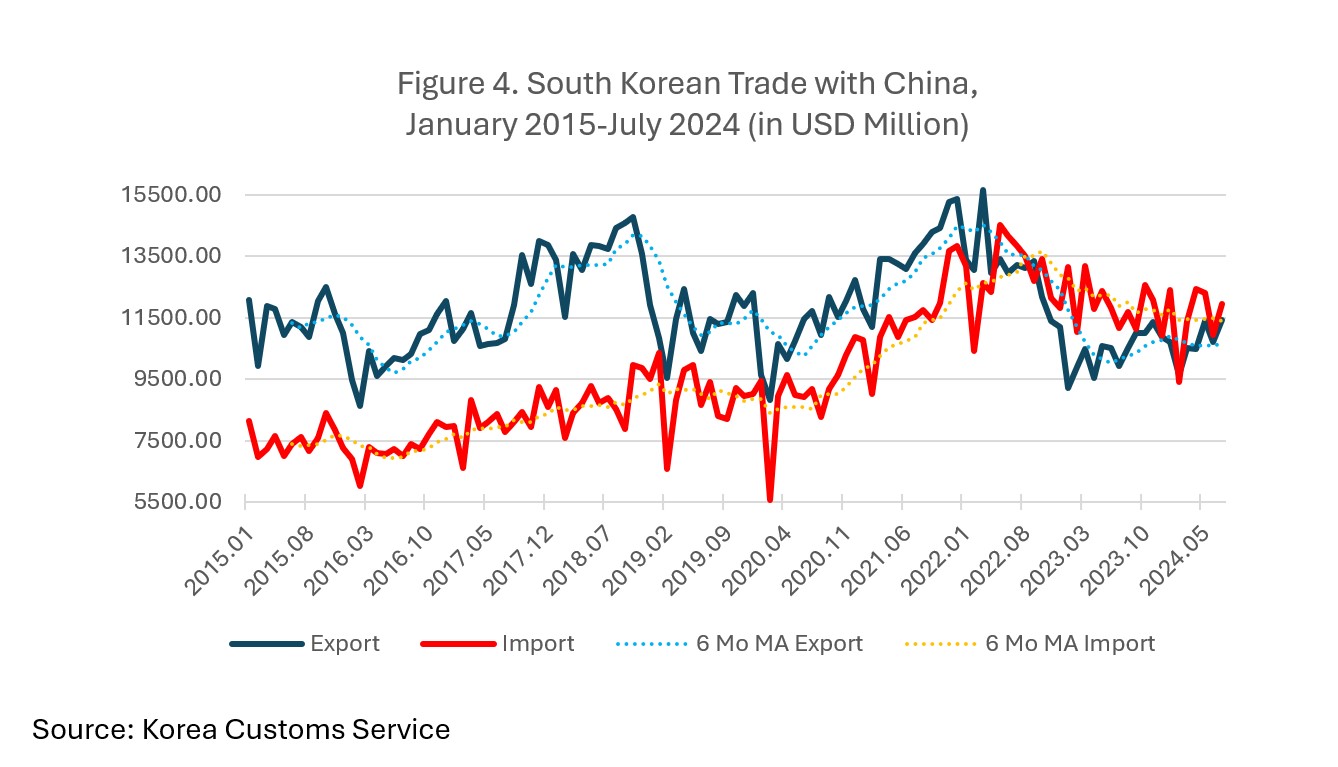

On the other hand, South Korea’s trade with China has declined sharply, led by a drop in exports over the past two years from a high of $15.6 billion in March 2022 to approximately $11 billion in July 2024 (Figure 4).

This data partially comports with the decline in China’s global imports from $230 billion to $215 billion during the same period. However, the trend within South Korea-China trade conflicts with China’s overall export performance, which actually increased by approximately $27 billion (an increase of 10 percent) from $272.9 billion in March 2022 to $300 billion in July 2024.

A closer look at China’s trade data suggests that much of the increase in its exports came from a growth in trade with the United States and Vietnam. For instance, between June 2023 and June 2024, exports to the United States and Vietnam increased by 6.6 percent to $2.8 billion and by 20.1 percent to $2 billion, respectively. The fact that China’s total trade increased from $500 billion in June 2023 to $517 billion in June 2024 suggests that the direction of trade between South Korea and China does not match the overall trade trends of both countries.

Top Exports from South Korea to China and the United States

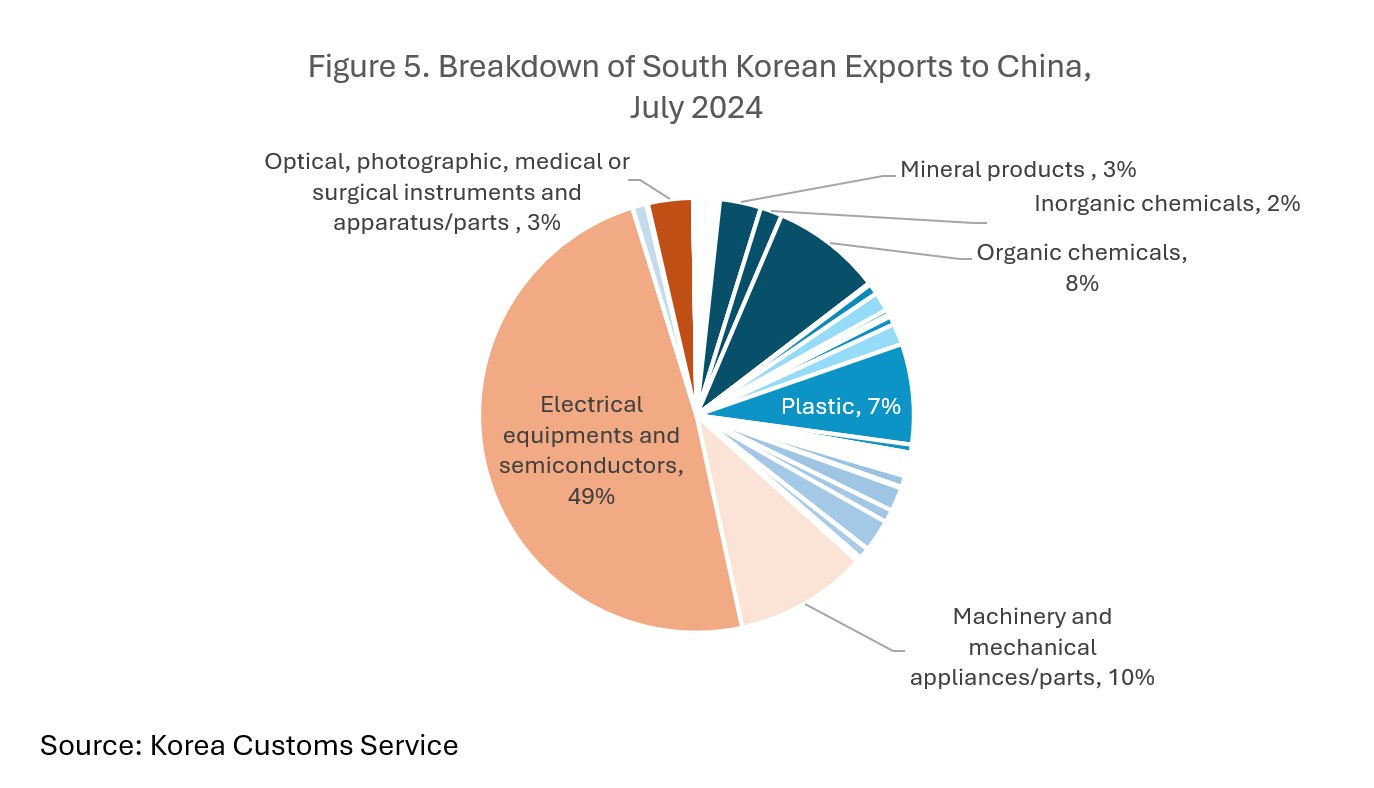

Aside from the quantitative difference in South Korea’s bilateral trade with its two largest trading partners, there is a difference in its qualitative content. For instance, approximately half of South Korean exports to China are electrical and semiconductor-related (49 percent), followed by mechanical appliances and machinery (11 percent), minerals and chemical products (13 percent), and plastics (7 percent). Together, these categories make up roughly 80 percent of South Korean exports to China, although a large proportion is concentrated in electrical and semiconductor-related goods (Figure 5).

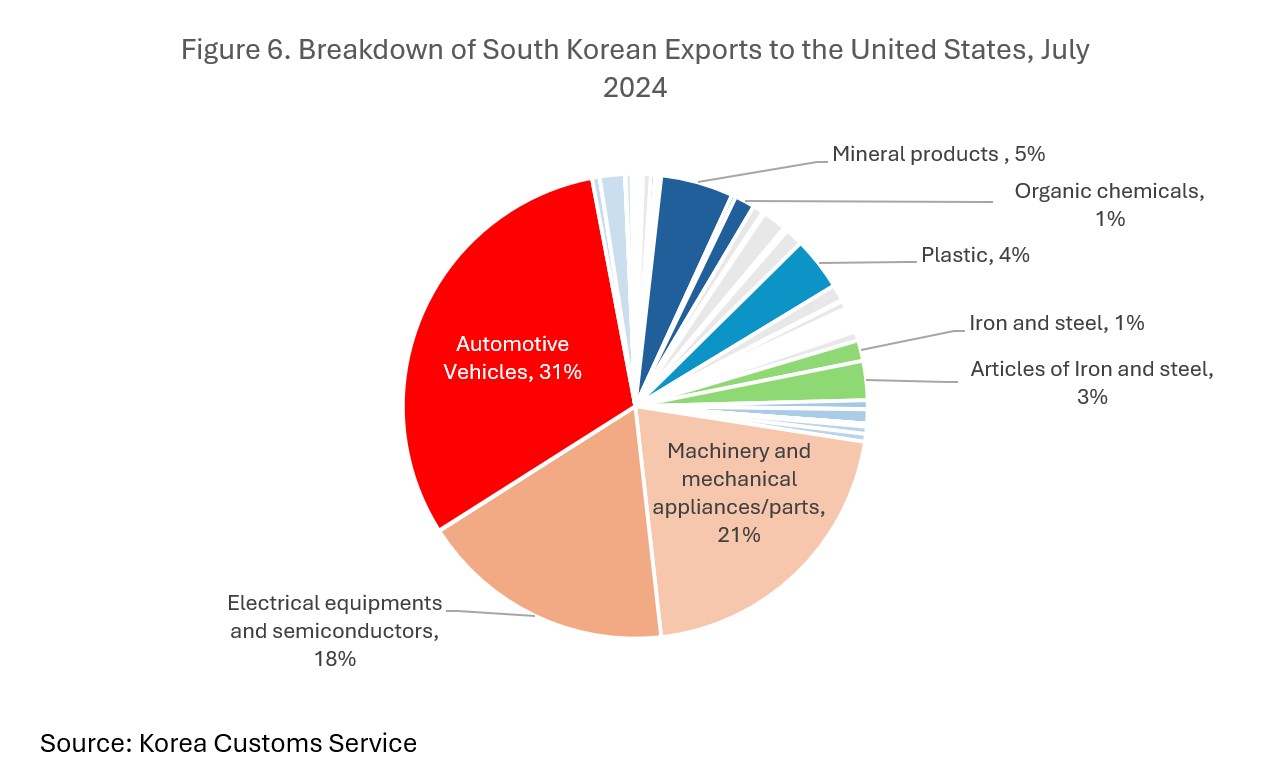

Exports to the United States are more evenly distributed among automotives (31 percent), mechanical appliances and machinery (21 percent), electrical and semiconductor goods (18 percent), minerals and chemical products (6 percent), plastics (4 percent), and iron/steel (4 percent). These products make up approximately 85 percent of South Korean exports to the United States (Figure 6). One common denominator between South Korea’s trade with China and the United States is semiconductor-related exports—namely, memory chips (HS 854232). While automotives are South Korea’s largest exports to the United States, the role of South Korean exports in the semiconductor space should also be watched closely.

Drivers and Implications of South Korea’s Trade Performance

The above data suggests that South Korea’s continued positive trade performance is largely fueled by a sustained increase in exports. Central to this story is the export of memory chips to China, Hong Kong, and Taiwan, but other destinations in Asia should not be ignored. Vietnam, India, the Philippines, and Japan combined accounted for 17 percent of all memory chip exports in June 2024, which is slightly higher than the amount exported to Taiwan (16.9 percent) in the same month. Adding to this mix is a strong outlook for future demand in products like SK Hynix’s high-bandwidth memory (HBM), which is an integral component of the AI accelerator package assembled by TSMC for the US-based NVIDIA.

Secondly, South Korean exports to the United States have grown consistently over the past decade and play an important role in South Korea’s overall trade performance. As shown in Figure 6, South Korea’s trade is robust due to a strong and steady US demand for automotives, mechanical appliances, and machinery, as well as electrical and semiconductor-related goods. Continued investment by South Korean manufacturers in the United States, encouraged by US industrial policies, can contribute to a positive medium- to long-term outlook for future trade. However, there are risks to increasing trade dependence on the United States, such as possible shocks to the financial, fiscal, and business environments. South Korea must prepare and manage these risks by continuing to diversify its trade and supply chain.

Thirdly, challenges in diplomatic ties between Beijing and Seoul, which dates back to the installation of a US missile defense battery in South Korea in 2016 and exacerbated by rising tensions between China and the United States as well as China’s self-reliant approach toward addressing domestic economic challenges, have contributed to shaping the quantitative and qualitative nature of South Korea’s recent trade with China. Flagging household demand, property sector contraction, and growing social pessimism have also been identified as contributing factors to China’s economic slowdown, which may also explain the decline in demand for South Korean exports. Not only does the recent data show a decline in the amount of trade between the two countries due to these developments, but it also suggests that the breadth of trade between China and South Korea is becoming narrower. It is unclear how to reverse this trend without significant changes to China’s stance on its economy and its foreign policy approach toward countries such as South Korea.

Dr. Je Heon (James) Kim is the Interim Director at the Korea Economic Institute of America. The views expressed here are the author’s alone.

Photo from Shutterstock.

KEI is registered under the FARA as an agent of the Korea Institute for International Economic Policy, a public corporation established by the government of the Republic of Korea. Additional information is available at the Department of Justice, Washington, D.C.