The Peninsula

The Supreme Court Case That Could Redefine U.S.-Korea Trade

Published November 4, 2025

Author: Tom Ramage

Category: Economic Security, Economics, Indo-Pacific, United States

The Supreme Court will soon decide whether the Donald Trump administration’s “reciprocal tariffs” are legal, and this decision will determine the future structure of U.S. trade policy and South Korea’s economic engagement with the United States. The case centers on whether the president can use the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA) to impose tariffs without congressional approval. For Korea, whose July 30 trade deal established a 15 percent baseline tariff alongside a USD 350 billion investment fund concluded on the sidelines of this year’s Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) meeting, a decision to strike down the tariffs would strengthen Seoul’s position on existing and upcoming Section 232 measures targeting autos, semiconductors, and industrial goods, while an affirmation would cement the “Trump Round” as the new framework for bilateral trade.

Section-specific 232 tariffs threatened by the Trump administration against steel and aluminum, semiconductors, wind turbines, robotics and industrial machinery, autos and auto parts, and other imports could remain in place due to their differing tariff authority under the Trade Expansion Act of 1962. If the Supreme Court overturns all IEEPA tariffs, one upshot could be a rebate for U.S. importers.

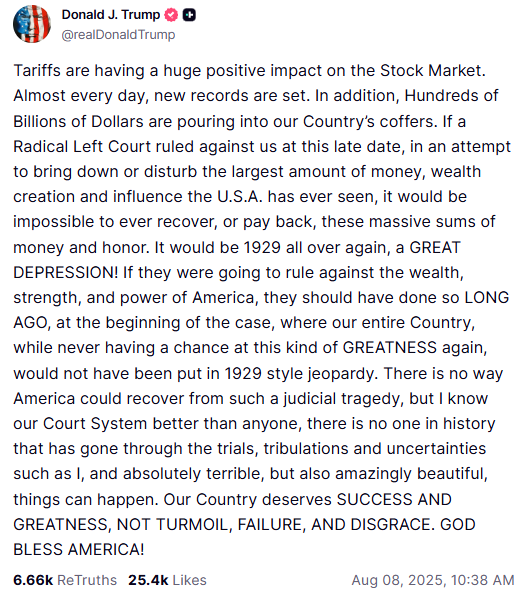

The government cannot retain money paid toward unlawful tariffs, but unless importers were specifically parties to the lawsuits challenging the tariffs, they would likely be eligible only if they file a protest with U.S. Customs and Border Protection, the agency officially responsible for collecting the tariff monies. It is likely that this will not come easily. U.S. Secretary of the Treasury Scott Bessent remarked that the government “would have to give a refund of about half,” without specifying beyond that. On August 11, the U.S. Department of Justice published a letter to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit warning of “catastrophic consequences” to U.S. national security, foreign policy, and economy. The United States “would not be able to pay back the trillions of dollars that other countries have already committed to pay,” the letter continued. President Trump has similarly suggested that the United States would enter another “GREAT DEPRESSION” if the country’s top court overturns his tariffs.

President Trump’s Truth Social post from August 8, indicating that it would be “1929 all over again” should the courts invalidate the IEEPA tariffs.

Whether a tariff ruling would trigger an economic downturn remains uncertain. What is clear is that the outcome will directly affect foreign exporters, particularly those in Korea, if U.S. importers receive tariff relief. What is unclear is the extent to which foreign companies would be eligible for, or benefit from, any potential rebate. According to the ITC World Trade Map, imports from Korea to the United States totaled roughly USD 128.4 billion in 2024 and USD 31.93 billion in Q2 2025 alone. But the costs of tariffs are nominally paid by the importer. Portions of the tariffs are passed on to the consumers through price increases. Accordingly, these costs are also shared with the foreign exporter through lower export prices. This is where Korean companies bear the cost of tariffs, along with their goods becoming less competitive compared to domestic goods as a result of higher prices on imported goods.

A reduction in import prices if IEEPA tariffs were suspended would likely halt price increases in the U.S. consumer market, but goods already affected by price increases may exhibit “price stickiness.” Firms may be hesitant to lower prices due to the tariffs (prices on imported goods have increased an average of 4 percent since March 2025). This means that even if tariffs were lowered, it could take a while for Korean exporters to the United States to regain their full competitiveness.

Any adjustment to pricing will also depend on the administration’s ability to pursue alternative legal mechanisms for imposing tariffs. Treasury Secretary Bessent has indicated that trade agreements the administration has already inked with countries, including Korea, will stay in place “even if the Supreme Court invalidates mutual tariffs,” citing “other means” by which the White House may impose them. One avenue may be Section 338 of the Tariff Act of 1930. The act allows the president to impose retaliatory tariffs on countries that discriminate against the United States, but it has limited precedent, putting it at greater risk of future legal challenges.

More consequential for Korea may be the tariffs that would remain in place under Section 232. According to the Korea Chamber of Commerce and Industry, autos and auto parts accounted for 57.5 percent of Korea’s Q2 tariff payments (which are estimated at USD 3.3 billion for that period). Other Section 232-targeted industries—such as semiconductors—could further expand Korea’s tariff obligations once investigations conclude and new measures take effect. This makes the outcome of IEEPA challenges comparatively less significant than the potential reduction or modification of the separate 232 tariffs.

If the court upholds the use of IEEPA to impose broad tariffs, it would fundamentally alter how U.S. trade policy is authorized and executed. Currently, Article 1, Section 8 of the Constitution assigns power “to lay and collect taxes, duties, imposts, and excises” to Congress. The power to implement tariffs and trade agreements would effectively shift from Congress to the White House, as has been the case in practice since January 2025. By using IEEPA to drive bilateral negotiations instead of the multilateral global trading system, the United States would affirm its new “Trump Round” of trade, locking in the deals concluded during the summer’s economic negotiations.

But if that does not occur, U.S. trade partners may find themselves taking a very different approach to economic engagement. Reciprocal tariff rates would effectively reset to zero, with attempts at resuscitation expected to follow. While the administration would likely pursue alternative ways to implement tariffs—being unlikely to easily give up a major cornerstone of its policy—such a ruling could, at the very least, put Seoul in a better position to engage going forward.

The coming weeks will offer a better picture of what any one of these scenarios may look like, all amid global economic volatility and complex international negotiations. Regardless of the outcome, the Supreme Court decision will mark the beginning of a new phase in how the United States structures trade with its partners.

Tom Ramage is Economic Policy Analyst at the Korea Economic Institute of America (KEI). The views expressed are the author’s alone.

Feature Image from Shutterstock.

KEI is registered under the FARA as an agent of the Korea Institute for International Economic Policy, a public corporation established by the government of the Republic of Korea. Additional information is available at the Department of Justice, Washington, D.C.