The Peninsula

The Rise of Self-deprecating Terms Such as “Hell Chosun” and “Dirt Spoon” among the Young Generations in Korea

Published October 24, 2016

Category: South Korea

By Sungeun (Grace) Chung

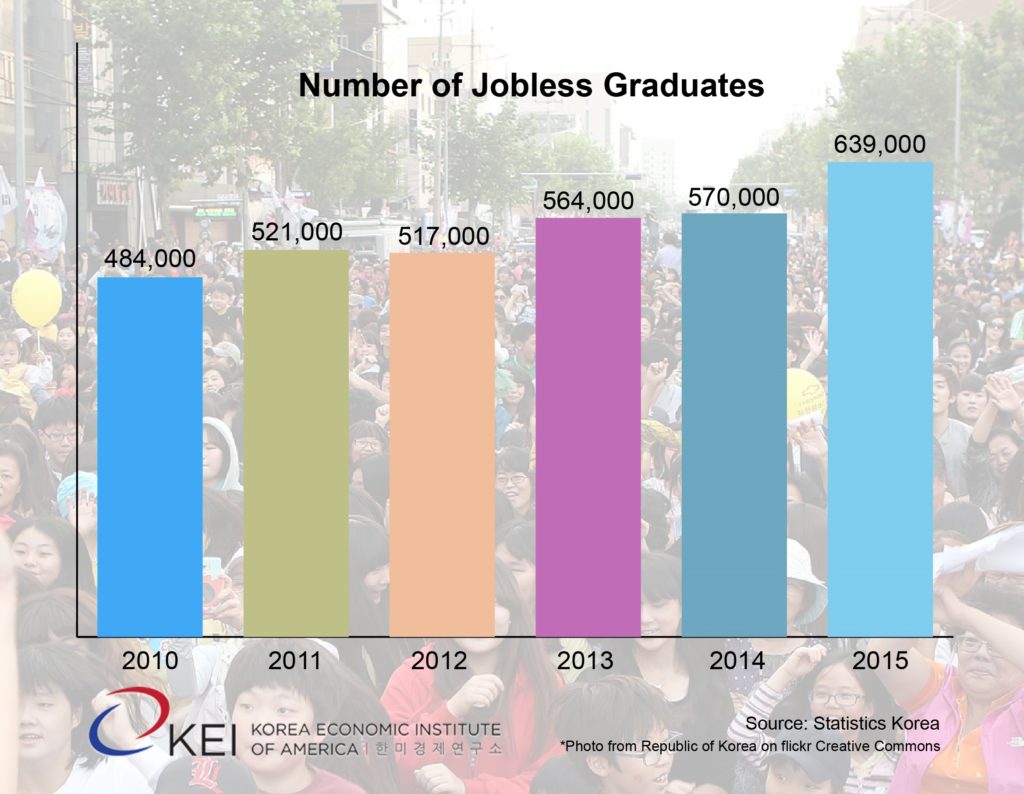

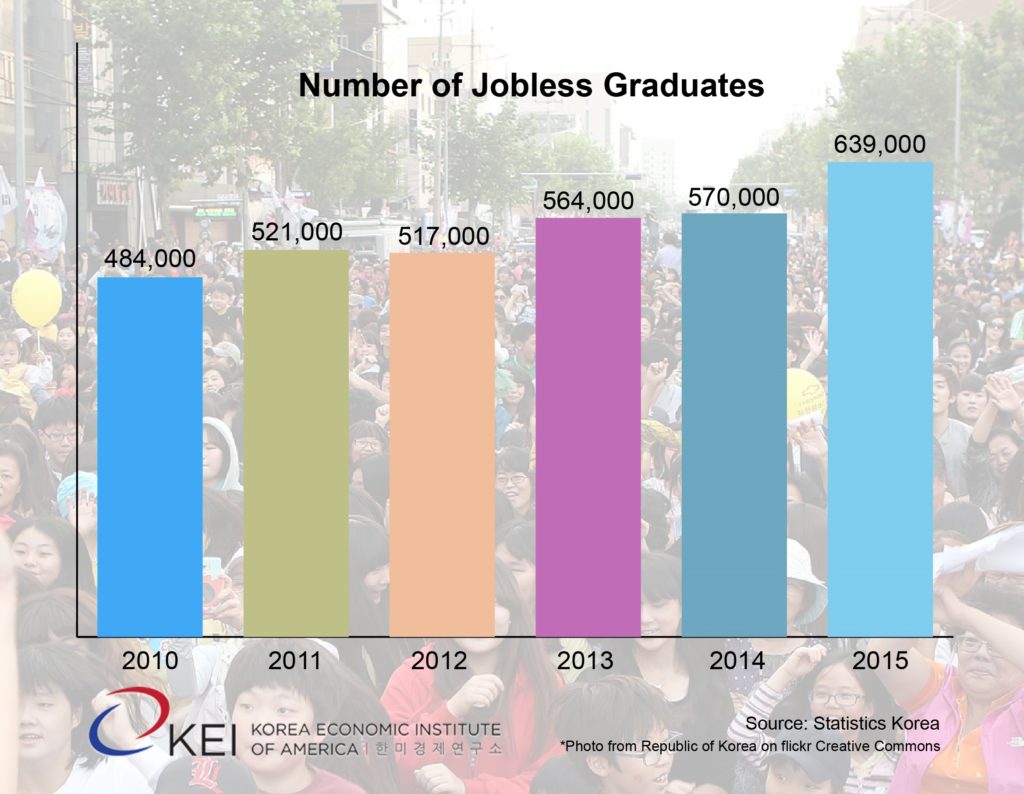

These days, college students graduate into a competitive job markets where a high unemployment rate and an oversupply of workers coexist. Yet the case of South Korea is extraordinary. Despite the miraculously rapid economic growth following the Korean War, which is referred to as the “Miracle on the Han River.” However, what they are now experiencing is an economic slump with high unemployment rate among youth (age 20-29), which is over 9.2 percent according to official government statistics. Nevertheless, this is merely not reflective of the full picture as data shows over 58% of South Korea’s youth is either unemployed or underemployed.

South Korea is very well known for its highly competitive academic system, which further suggests a lingering oversupply of graduates. The Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) figures indicate that69% of Korean millennials have a college degree, which is the highest among OECD countries in 2015.

South Korea is very well known for its highly competitive academic system, which further suggests a lingering oversupply of graduates. The Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) figures indicate that69% of Korean millennials have a college degree, which is the highest among OECD countries in 2015.

Recent graduates’ unrealistic expectations and parental pressure may also be contributing factors. Not only those who graduated from top universities, but also those who graduated from mid to lower ranked universities wish to get a job at South Korea’s conglomerates, the chaebol companies, such as Samsung, LG, Hyundai, etc. Ironically, most Koreans criticize the chaebol companies for their corruption and continuous dominance in Korea’s economy because of its interlocking management system. Moreover, most people who work at those prestigious companies have to give up their evenings for working overtime. They abandon their own life values: love, marriage, childbirth, human relations, home ownership, personal dreams, and hope, which reveals what seven give-up generation means. Then, new problems such as the lowest fertility rates and the highest suicide rates rise among the society. Nonetheless, many young jobseekers still want to give the major corporations a shot or companies that have a higher name value because they usually offer better benefit packages and pay better than most Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs).

However, South Korea’s economic slump makes it harder for the conglomerates to offer more positions than they can afford, and eventually they announce reduced hiring, which becomes dreadful news for the young desperate jobseekers. Despite Park Geun-hye Administration’s plan to reform the labor market by suggesting to 17 chaebol companies that they increase recruitment, the positions offered would be mostly unpaid or minimum paid internships or contractors. Along with school, but without time to prepare for English or Chinese qualification exam, multiple step interviews, and aptitude tests at each company, most young in Korea live their lives cramming through the night.

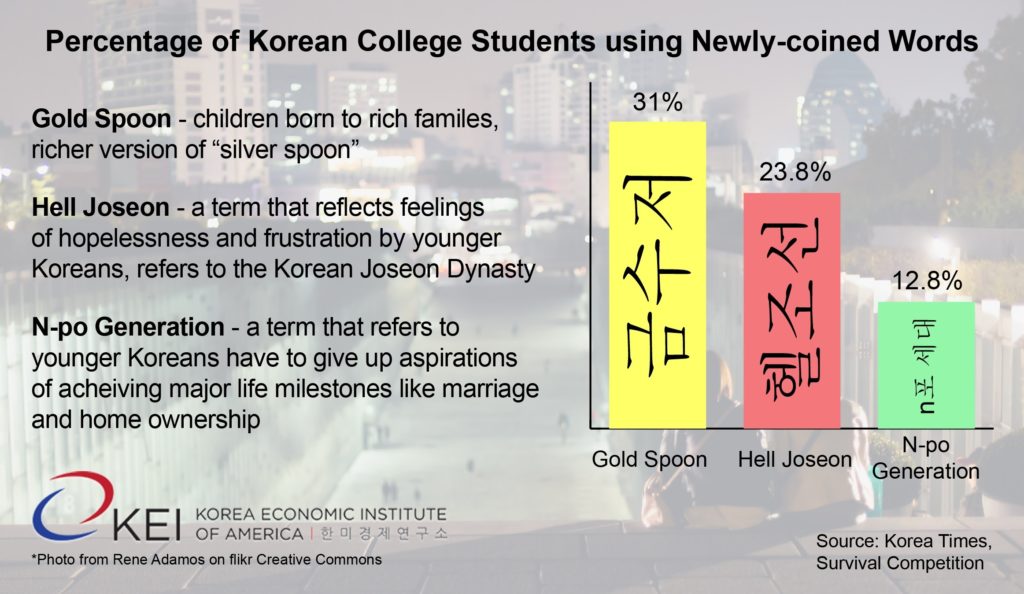

All these devastating factors combine together to create pessimistic terms such as “Hell Joseon” and “Dirt Spoon” that satirize the reality of Korea’s social problems. First, “Hell Joseon” refers to the pre-modern Korean government with a strong class system, gender inequality, and poor leadership as a Korean policy researcher from Asan Institute for Policy Studies, Jiyoon Kim, suggests in her article from Georgetown Journal of Asian Affairs. Gaining its currency from social media use, the term reveals the hopelessness of the younger generations as well as the lack of hope for further economic growth that would alleviate the challenges faced by the young. Se-woong Koo for Korea Exposé describes “Hell Joseon” as an infernal feudal kingdom stuck in the nineteenth century. When using the term, they mean that past generations, if they worked hard enough, got a satisfying job and compensation. However, no matter how hard they work nowadays, the young generations would still live in “Hell Joseon” with continuous economic dominance of chaebol companies and an extremely competitive job market.

Secondly, the widely used “spoon theory” derives from the idea of those “born with a silver spoon in one’s mouth.” Korean youth created the theory to categorize themselves into one of the following “spoons”: a golden spoon, a silver spoon, and a dirt spoon. A golden spoon refers to those born to a chaebol or very rich family, a silver spoon to those born to a relatively well-off or middle-class family, and lastly a dirt spoon to those born to a low-income family. In Korea, we see many examples of golden or silver spoons getting a job with parents’ backing or inheriting family’s prosperity and that of dirt spoons struggling between making a living on their own and finding a real job that may help to break the cycle of inherited poverty. The spoon theory points out that the rich become richer, and the poor become poorer. The gap between the rich and the poor persists especially with the existence of chaebols and its ownership inheritance system.

Secondly, the widely used “spoon theory” derives from the idea of those “born with a silver spoon in one’s mouth.” Korean youth created the theory to categorize themselves into one of the following “spoons”: a golden spoon, a silver spoon, and a dirt spoon. A golden spoon refers to those born to a chaebol or very rich family, a silver spoon to those born to a relatively well-off or middle-class family, and lastly a dirt spoon to those born to a low-income family. In Korea, we see many examples of golden or silver spoons getting a job with parents’ backing or inheriting family’s prosperity and that of dirt spoons struggling between making a living on their own and finding a real job that may help to break the cycle of inherited poverty. The spoon theory points out that the rich become richer, and the poor become poorer. The gap between the rich and the poor persists especially with the existence of chaebols and its ownership inheritance system.

According to a survey of 350 college students from Hanyang University by the Hanyang Journal, one of the top ranked schools in Korea, 68% of Hanyang students said that one’s parents’ socio-economic status greatly or somewhat influences his or her future. About 52% of them believe that it is possible to overcome their “spoon class,” but almost half were pessimistic and overwhelmed by the “spoon class system.”

Nevertheless, the sad part is that the people who brought these terms to prominence are the ones that think they are disadvantaged from living in “Hell Joseon” and from being a “dirt spoon.” They are using these terms to criticize the societal problems, yet at the same time, they are using these self-deprecating phrases that insult their own backgrounds.

No one denies the harsh reality of Korean society because it is true, but self-deprecation out of frustration and depressing feelings can backfire because it worsens concerns and uncertainties, and deepens a sense of alienation and insecurity. Some experts also see that self-destruction is not a form of escape from reality, and government’s active efforts for public engagement are very necessary as well. On the other hand, Korea Times’ deputy managing editor, Park Yoon-bae, believes that that Korea’s outdated socioeconomic structure may be the reason, and that Korea needs to create a new system for sustainable and inclusive growth.

It is true that young generations in Korea “live through pain,” which involves high academic ambitions, a competitive job market, uncertain job and financial security, inequality and a cycle of inherited wealth or inherited poverty, and corruption within the upper socio-economic classes and government. Yet presumably what South Korea is in need of is a new system for economic growth and for justice and equality.

Sungeun (Grace) Chung is an intern at the Korea Economic Institute of America and a graduate of University of Wisconsin-Madison with majors in Economics and Mathematics as well as a minor in East Asian Studies. The views expressed here are the author’s alone.

Photo from Hyunwoo Sun’s photostream on flickr Creative Commons.