The Peninsula

The Korean Economy in the Face of the Coronavirus Pandemic

By Randall S. Jones

Korea’s Success in Containing the Coronavirus Pandemic

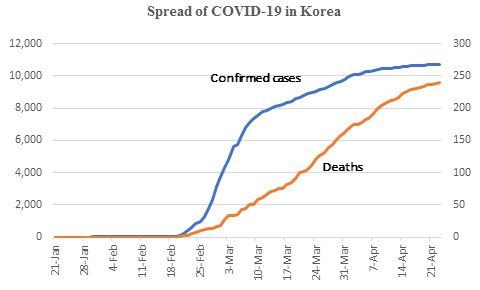

Korea has been able to contain the coronavirus thanks to the prompt implementation of effective policies. The number of new daily COVID-19 cases peaked at 909 on 29 February. At that point, Korea had the second-largest number of recorded cases in the world after China. Government policies and the efforts of its citizens enabled Korea to “flatten the curve,” reducing the number of new cases to below ten per day (figure below). The mortality rate, with less than 250 deaths nationwide thus far, is also low compared to many countries. Korea’s successful response has prompted more than 120 countries to request its help in fighting the coronavirus. Moreover, Korea has become a major supplier of coronavirus test kits to a number of countries, including the United States.

Source: Ministry of Health and Welfare (ncov.mohw.go.kr).

After the first reported COVID-19 infection on 20 January, the government responded quickly, based on lessons learned during the SARS outbreak in 2003 and the 2015 MERS epidemic. Within a week, government officials met with 20 medical and pharmaceutical companies to launch the production of tests for the coronavirus. Two weeks after the first case was confirmed, the government approved and distributed test kits capable of producing results in six hours. More than 600 testing centers, including 70 drive-through facilities, were established. By March22, Korea had tested six times as many persons as the United States on a per capita basis.

In addition, Korea used information and communications technology (ICT) to trace contacts, leading to the isolation and quarantine of persons exposed to the coronavirus. The Cellular Broadcasting Service (CBS) enables government agencies to transmit emergency alert text messages to cell phones. The CBS was used to inform the public of the movement of persons infected with the virus. Those who had come into contact with an infected person were thus prompted to get tested quickly. In sum, ICT has facilitated social distancing, rapid testing and detailed tracing of persons infected with COVID-19, thereby playing a key role in flattening the curve. According to Thomas Byrne, president of the Korea Society, “the high degree of transparency and competency of South Korean health officials provides helpful lessons about containment efforts for other countries, and about the nature of this pandemic for the international scientific community”.

Given the rapid and successful implementation of testing, tracing infected persons and quarantines, Korea’s social distancing policies were less stringent than the draconian shutdown measures adopted in other major economies. Indeed, Korea avoided lockdowns on cities or regions. Instead, the “high-intensity” social distancing program introduced on March 22 strongly advised many public establishments, such as private educational institutes, religious facilities and gyms to close temporarily or to disinfect their facilities regularly and require visitors to wear face masks at all times. Companies were advised to run staggered work schedules or allow employees to work from home, check workers’ body temperatures every day and cancel or postpone business trips. On April 21, with the number of new cases falling to below ten per day, the government announced that many businesses and organizations that had previously been advised to shut down were allowed to resume their activities as long as they abide by basic hygiene rules.

The Economic Impact of the Pandemic

Korea’s outstanding response to the coronavirus did not spare it from a severe economic impact:

- Retail sales fell 6.0% in February (month-on-month), despite an 8.4% rise in on-line purchases.

- Manufacturing production declined 4.1% (month-on-month), despite increased output of semiconductors. This was offset, however, by a 28% drop in car production, the largest in 13 years. Meanwhile, output in services declined by 3.5%, as sales in the hospitality and restaurant sectors plunged.

- Falling output led to a 195,000 decline in employment in March (year-on-year), the largest decline since the Great Recession. Moreover, companies reduced costs by cutting back on working hours and sending employees on temporary leave in order to minimize layoffs. The number of employees taking temporary leave surged by 1.23 million to 1.6 million in March, the sharpest rise since 1983. The number of furloughed workers exceeds the number of unemployed (1.18 million).

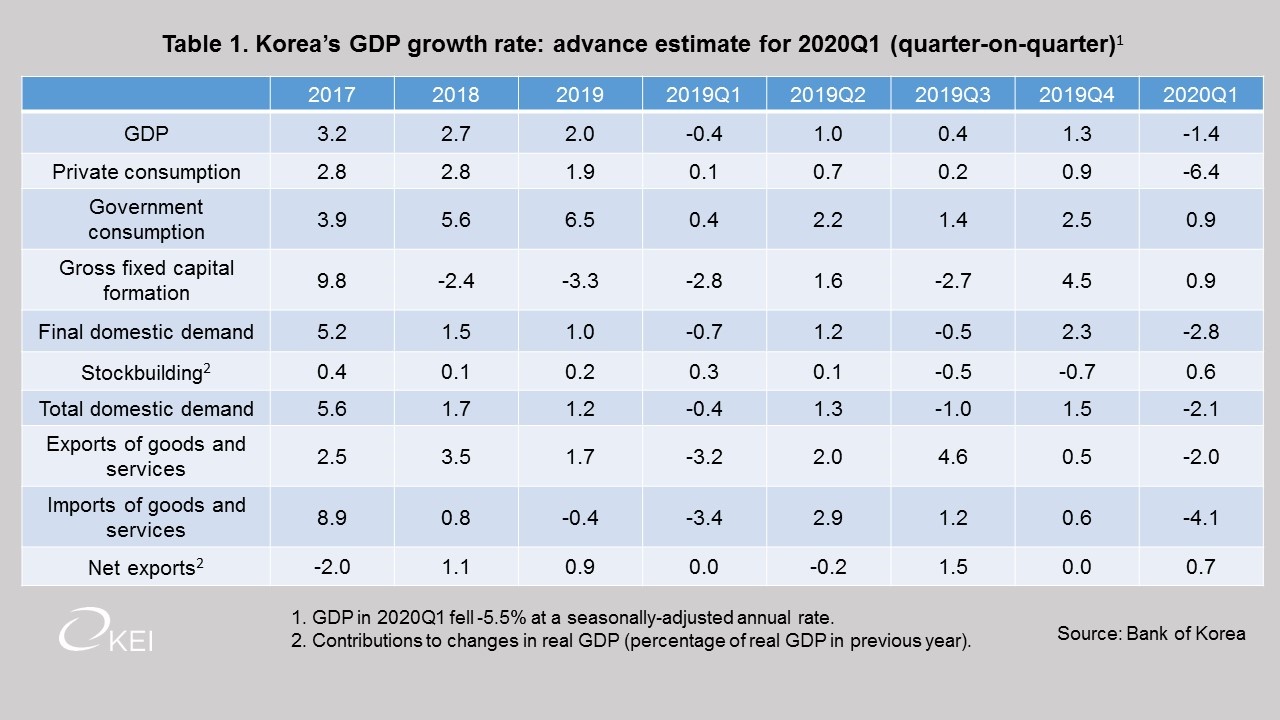

The impact of the pandemic led to a 1.4% (quarter-on-quarter) drop in real GDP in the first quarter of 2020, the largest decline since 2008 (Table 1). Still, the decline was much less than the 9.8% (quarter-on-quarter) plunge in China. Korea’s first-quarter contraction was driven by a -6.4% fall in private consumption. This decline was partially offset by government consumption and fixed capital formation. In addition, stockbuilding and net exports made positive contributions, reflecting the double-digit fall in imports.

Policies to Support the Economy

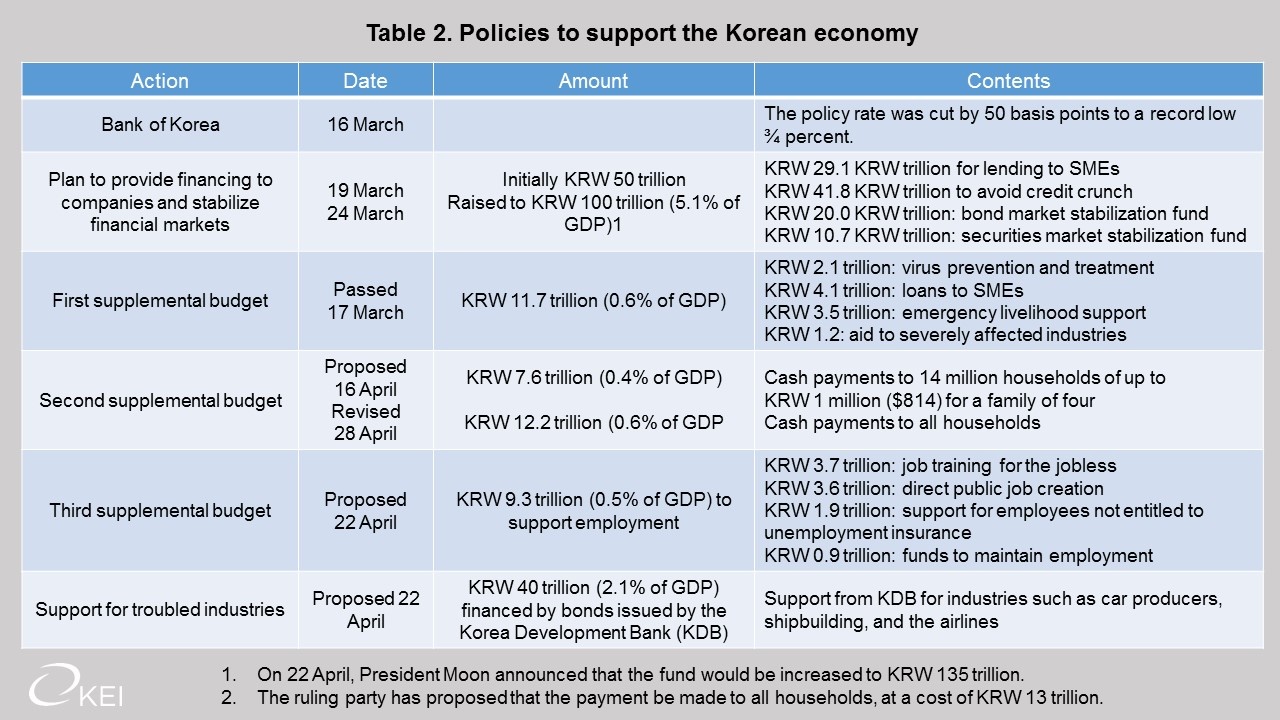

The authorities have taken a number of measures to stem the downward spiral (Table 2). The Bank of Korea cut its policy interest rate by 50 basis points to a record low of ¾ percent at its March 16 emergency meeting. The central bank said that “monetary policy accommodation is called for in order to ease volatility in the financial markets and reduce the effects on future economic growth and inflation”. A few days later, the Bank of Korea signed a $60 billion bilateral currency swap agreement with the U.S. Federal Reserve, which has helped stabilize Korean financial markets. In addition, the central bank also broadened the eligible collateral for open market operations to maintain adequate liquidity in financial markets.

On 19 March, the government launched a KRW 50 trillion fund to provide funding for SMEs and large companies (Table 2). The fund is also being used to stabilize financial markets, as yield spreads for corporate bonds relative to government bonds rose to their highest level since 2012, while the stock market fell by one-third by mid-March relative to its level at the beginning of 2020. President Moon doubled the initiative on March 24 to KRW 100 trillion (5.1%) of GDP and on April 22 announced plans to increase it further to KRW 135 trillion. To promote lending to small firms, the President met with major financial institutions, including commercial banks, state banks and public institutions, and financial regulators in early April to encourage them to speed up the processing of loan applications. While recognizing that this could lead to mistakes, President Moon promised that “There won’t be a situation where the government or the financial authorities ask whose fault it was. I can promise you that clearly.”

In addition, supplemental budgets are providing fiscal support. The first extra budget, passed on March 17, provided KRW 11.7 trillion (0.6%) of GDP for virus prevention and treatment, loans to SMEs, emergency livelihood support and aid to severely affected industries. Following the April 15 election, a second supplementary budget of KRW 7.6 trillion (0.4% of GDP) was proposed to provide cash payments to households. Around 14 million households, representing the lower 70% of the income distribution, would receive up to KRW 1 million won ($820), according to the number of people in the household. On April 28, it was decided to give cash payments to all households, regardless of income, which boosted the cost to KRW 12.2 trillion (0.6% of GDP). However, the “universal welfare” is less effective in supporting demand than focusing on low-income households.

Finally, on April 22, President Moon announced a third supplementary budget of KRW 9.3 trillion (0.5% of GDP) to stabilize the labor market. The funds will create public jobs, provide job training and support for those without jobs, give emergency help to employees who do not qualify for unemployment insurance and help firms maintain employment. At the same time, President Moon announced a KRW 40 trillion (2.1% of GDP) for struggling industries, such as car producers, shipbuilding, and the airlines. The Korea Development Bank (KDB), a state-owned bank, will issue bonds guaranteed by the government to finance the assistance. Firms must meet certain conditions, such as maintaining employment, to receive support.

The measures taken or planned shown in Table 2, including liquidity provisions and credit guarantees amount to KRW 173 trillion (8.9% of GDP), In comparison, the $2 trillion Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act signed on March 27 amounts to 9% of U.S. GDP. Given Korea’s relatively low level of public debt, amounting to less than 40% of GDP compared to the OECD average of 109%, it appears to have space for further fiscal support to overcome the crisis. President Moon has instructed his economic team to push for a Korean-version New Deal to launch major infrastructure projects.

Korea’s Economic Outlook

It is an exceptionally difficult time to make projections given the great uncertainty about the path of the pandemic and the eventual size and effectiveness of government countermeasures. The International Monetary Fund recently predicted that Korea’s economy will shrink 1.2% in 2020, as the global economy is forecast to contract by 3.0%, its worst year since the Great Depression of the 1930s. Still, the Fund’s projected decline in Korea in 2020 is relatively small compared to other advanced economies, such as Japan (-5.2%), the United States (-5.9%), the United Kingdom (-6.5%) and the Euro area (-7.5%).

Korea has two important advantages. First, as noted above, Korea’s social distancing measures, which were already less stringent than most countries, were relaxed on April 21 and may be further eased in early May. The relaxation of social distancing may facilitate a rebound in the service sector, which accounts for about 60% of GDP. However, the sharp plunge in the consumer sentiment index in April to its lowest level since December 2008 will make any rebound gradual.

Second, the scope for further fiscal support was enhanced by the landslide victory of President Moon’s Democratic Party in the April 15 National Assembly election. The Democratic Party and an allied party won 180 seats in the 300-member National Assembly, an unprecedented result. After three years of slow economic growth, President Moon’s popularity had fallen below 50% in January 2020. However, the government’s success in containing the coronavirus boosted his support to as high as 58% prior to the election, allowing President Moon to avoid the usual lame-duck status of Korean presidents during their final years in office.

Korea was able to achieve a strong rebound from the 2008 Great Recession thanks in part to vigorous fiscal action. Indeed, the 2010 OECD Economic Survey of Korea stated “Korea has achieved one of the fastest recoveries in the OECD from the global recession. The government implemented the largest fiscal stimulus package among OECD countries”. The strong rebound facilitated the withdrawal of temporary stimulus, allowing Korea to return to its usual government budget surplus (on a general government basis).

However, there is great uncertainty about exports, another key driver of the 2009 rebound. As the 2010 Korea Survey noted, “The depreciation of the won – by 25% in effective terms during the six months from August 2008 – combined with strong demand from China laid the foundation for an export-led recovery”. Thus far, though, the outlook for the Chinese economy – and the world economy at large — is much weaker, as noted above. Moreover, the depreciation of the won since the beginning of 2020 has been relatively modest at around 6% relative to the dollar. The 27% decline in Korean exports (year-on-year in dollar value) during the first 20 days of April is not encouraging. Exports of semiconductors and cars fell by 14.9% and 28.5%, respectively. Exports are declining to all major partners, including China (-17.0%), the United States (-17.5%) and the European Union (-32.6%). Given the weakness of exports, which account for more than 40% of the Korean economy, the recovery from the pandemic is likely to be slow and gradual.

Randall Jones is a Visiting Fellow at Columbia University and a Non-Resident Fellow at the Korea Economic Institute of America. The views expressed here are the author’s alone.

Photo from sinano1000’s photostream on flickr Creative Commons.