The Peninsula

South Korea’s Not Out of the Woods Yet on U.S. Trade Actions

By Phil Eskeland

While many have expressed relief over reaching a tentative deal on limiting steel imports from the Republic of Korea (ROK) to the U.S. and modifying the Korea-U.S. Free Trade Agreement (KORUS FTA) with respect to maintaining the alliance, South Korea still could get caught in the cross-fire between China and the United States on trade and security.

Last Thursday, the Trump Administration announced the results of its investigation into violations of U.S. intellectual property (IP) rights by China through forced technology transfers, discriminatory licensing practices, and cyber intrusions. The U.S. Trade Representative (USTR) found that China’s policies have resulted in at least $50 billion in harm to the U.S. economy. As a result, the Trump Administration has proposed three responses to these violations:

- Impose a 25 percent tariff on certain high-technology products from China, including aerospace, information and communication technology (ICT), and machinery.

- Bring a dispute settlement resolution case to the World Trade Organization (WTO) regarding these Chinese IP violations; and

- Restrict Chinese investment in key U.S. technology industries.

The Trump Administration is basing its action on a part of U.S. trade law (Section 301 of the Trade Act of 1974) that has not been frequently used since the responsibilities of the post-World War II era General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) system was transferred to the World Trade Organization (WTO). Prior to 1994, Section 301 was used to combat unfair trade practices by other nations (beyond anti-dumping and illegal government export subsidization accusations) because the GATT system did not have an enforcement mechanism to sanction countries when they violated their international trade obligations. The WTO became the successor international regime to the GATT precisely for the reason to have binding authority to resolve trade disputes among member nations.

Since the WTO assumed the responsibilities of the GATT, the United States has prevailed 91 percent of the time in trade disputes it brought against other nations. Also, objections by other countries against inconsistent Chinese trade practices have prevailed in all instances at the WTO when the complaint was fully pursued. Thus, the odds are in favor of success through the U.S. filing a dispute settlement resolution case at the WTO, particularly in dealing with China.

In addition, the European Commission challenged the United States use of Section 301 at the WTO in 1998. As a result, the USTR committed to “use its statutory discretion to implement Section 301 in conformity with WTO obligations.” This explains the rational for the Trump Administration to file a case at the WTO while also seeking to impose Section 301 tariffs, even though it appears to be a duplicative effort. The critical difference is the time it takes to arbitrate a trade dispute. Most WTO cases take approximately 15 months to fully adjudicate. However, it appears that the Trump Administration wants to impose tariffs against Chinese high-technology products within a shorter period of time.

In the middle of this trade fight is South Korea. Forty-two percent of Korea’s economy is reliant on exports. South Korea’s largest trading partner is China. Because Korea exports 29 percent of its intermediate goods and 23 percent of capital goods to China, higher U.S. tariffs on Chinese products will also leave Korea’s economy vulnerable to a trade spat because many of these Chinese products incorporate parts from South Korea. Possible U.S. pressure on China to specifically shift some of its semiconductor purchases away from Korean companies should also be of concern. It would be odd for a country like the U.S. that prides itself on free and open markets to have the government dictate where parts should come from to be incorporated into a final product.

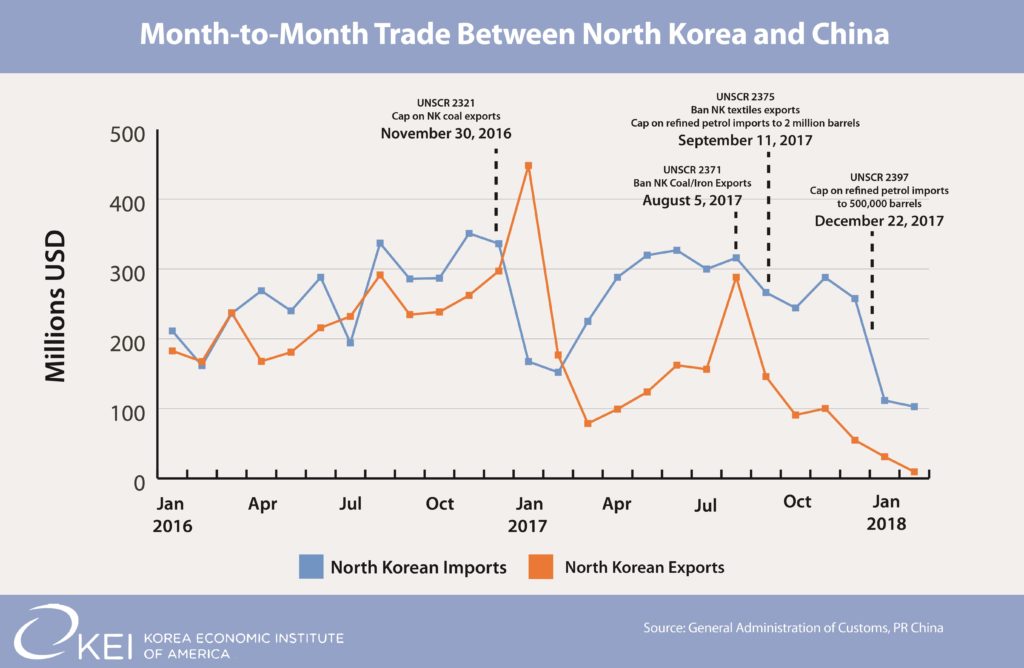

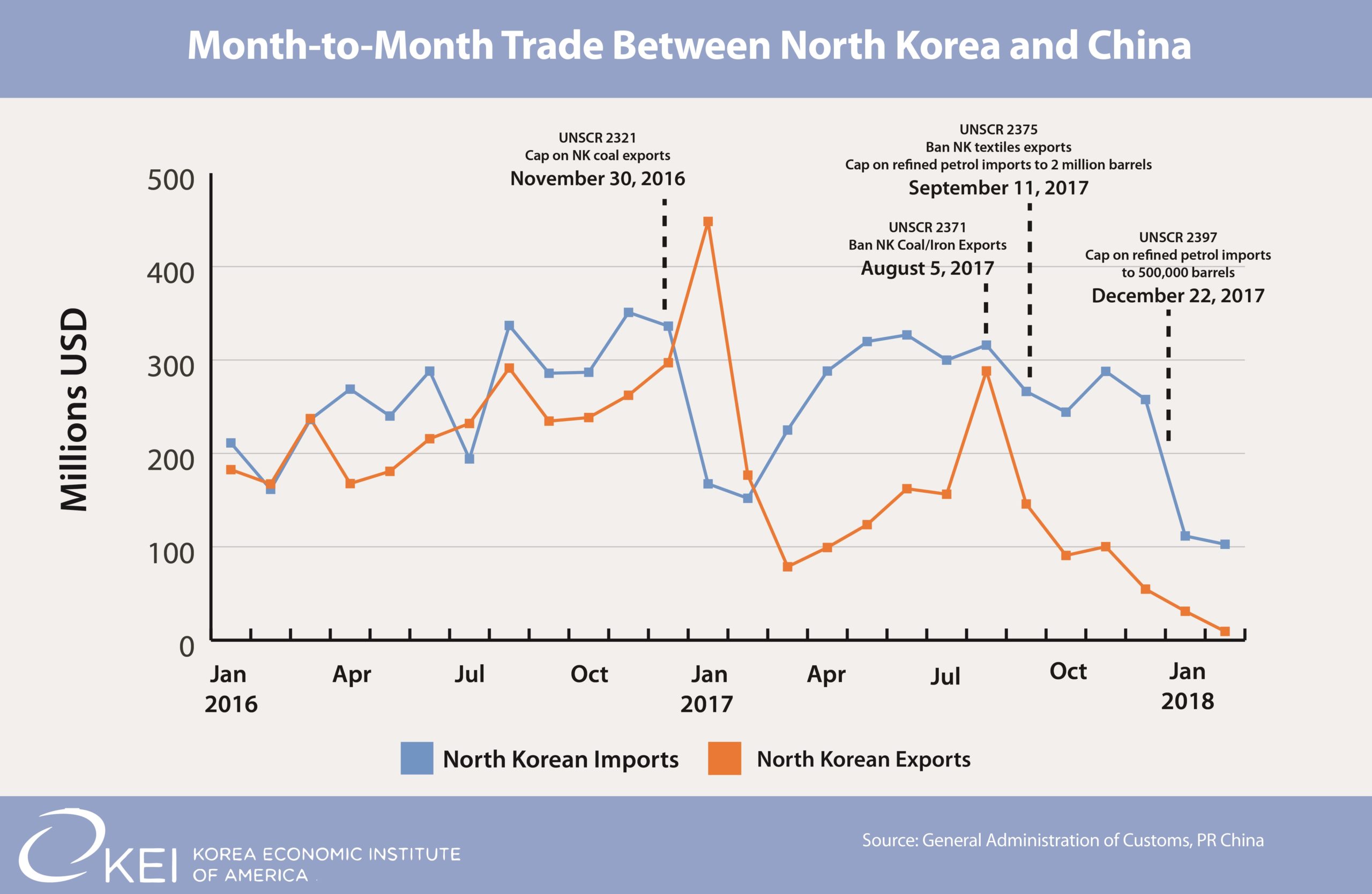

In addition, the unilateral trade action by the U.S. could complicate the upcoming summit meetings with North Korea. Last year, President Trump offered to not go tough on China’s trade policies in return for cooperation on denuclearizing North Korea. Recent customs data shows that China has dramatically reduced its bilateral trade with North Korea in the last few months in response to U.S. and international pressure. However, if the U.S. proceeds with placing higher tariffs on certain Chinese high technology products outside the bounds of the WTO, China may perceive this to be a breach of good faith on the part of the United States. China does not compartmentalize its relations with the outside world, and there could be a less vigorous enforcement of United Nations sanctions on North Korea by Chinese authorities if the U.S. unilaterally proceeds with imposing higher tariffs on Chinese products under Section 301.

This is not the best course of action. Any U.S. tariff imposed on Chinese products not authorized by the WTO will provoke China to impose a similar level of duties against U.S. exports (most logical target – U.S. agricultural commodities, such as soybeans, that China can easily purchase elsewhere) while they also file a parallel dispute settlement case in the WTO against the U.S. government’s misuse of Section 301. In addition, China could have a rapprochement with its erstwhile ally, North Korea, particularly if the visit of a high-level delegation from the DPRK results in a commitment to not engage in further nuclear or missile tests. A better course would have been to organize a coalition of like-minded nations, including South Korea, to join the U.S. in a WTO case to combat Chinese violations of intellectual property rights. Then, China would be required to change its domestic policies to respect IP or face the consequences of WTO-approved trade sanctions. This would not start a “tit-for-tat” global trade war with an escalation in tariffs that would have a host of unintended consequences, including catching nations like Korea in the cross-hairs in terms of both economics and security.

Hopefully, it is not too late. Already, there are behind-the-scenes discussions between the U.S. and China to avert a possible trade war. If both sides can reach an accommodation fairly soon, it will restore stability and predictability to global markets and not negatively affect strong allies such as South Korea in the quest to deal with a legitimate problem of IP violations by China. It would also send a positive signal to the world that the America stands behind the WTO as the guarantor of international trading rules that were established under the leadership of the United States. Finally, it would not affect the continued maximum pressure and engagement campaign, currently supported by China, to peacefully denuclearize the Korean peninsula.

Phil Eskeland is Executive Director for Operations and Policy at the Korea Economic Institute of America. The views expressed here are his own.

Photo from the White House’s photostream on flickr Creative Commons.