The Peninsula

South Korea’s Emergence as a Hub in the Global Art Market

“You can either buy clothes or buy pictures.” (Gertrude Stein)

The air will be filled with a different kind of buzz in Seoul this week as it hosts the third annual international art fair, Frieze Seoul. Over 110 leading art galleries worldwide will assemble for four days at the COEX Convention and Exhibition Center in Gangnam to showcase various works of contemporary art to guests and collectors. There promises to be no shortage of side events taking place throughout the city in coordination with the exhibit. Attendance this year is expected to be similar to the past two years at about 70,000 participants, which is larger than Frieze Los Angeles (roughly 35,000) and Frieze New York (roughly 25,000) combined but still slightly smaller than Art Basel Hong Kong or Frieze London (each at about 85,000). The event is part of a broader trend that suggests South Korea is emerging as a tour de force in the art world.

Contours of the South Korean Art Space

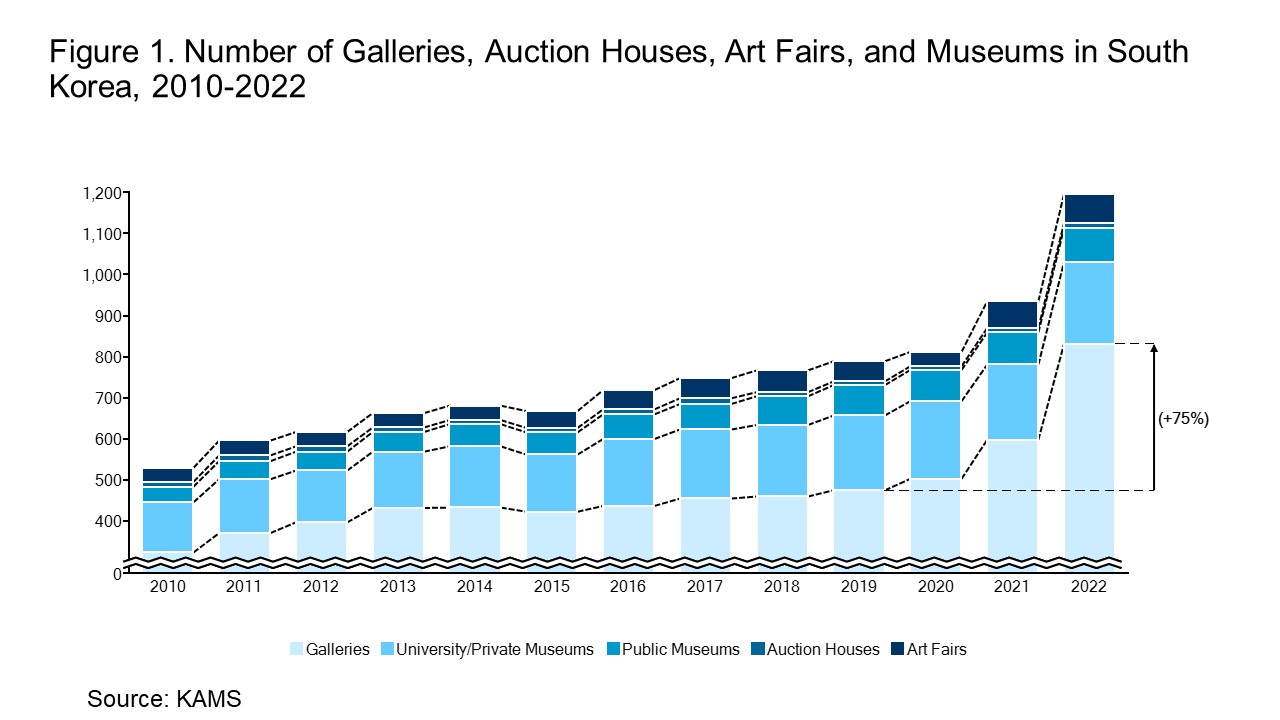

Although the global art market experienced a general contraction in 2023, the relative position of key players did not change significantly. The available figures from Korea suggest that the future remains promising. Data compiled by the Korea Arts Management Service shows that the number of private gallery spaces in South Korea increased by 75 percent from 475 in 2019 to 831 in 2022, which is an annual average growth of about 21 percent compared to a pre-pandemic growth rate of 4.4 percent dating back to 2010 (Figure 1).

The number of publicly operated museums also grew modestly from 70 in 2018 to 83 in 2022, while privately owned museums grew from 174 to 199 in the same period. The number of art fairs increased from a high of 53 in 2018 to 71 in 2022 (an increase of 34 percent), helped in part by the continuing investment from South Korea’s Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism (MCST) in this domain (see below).

Trends in the South Korean Art Market

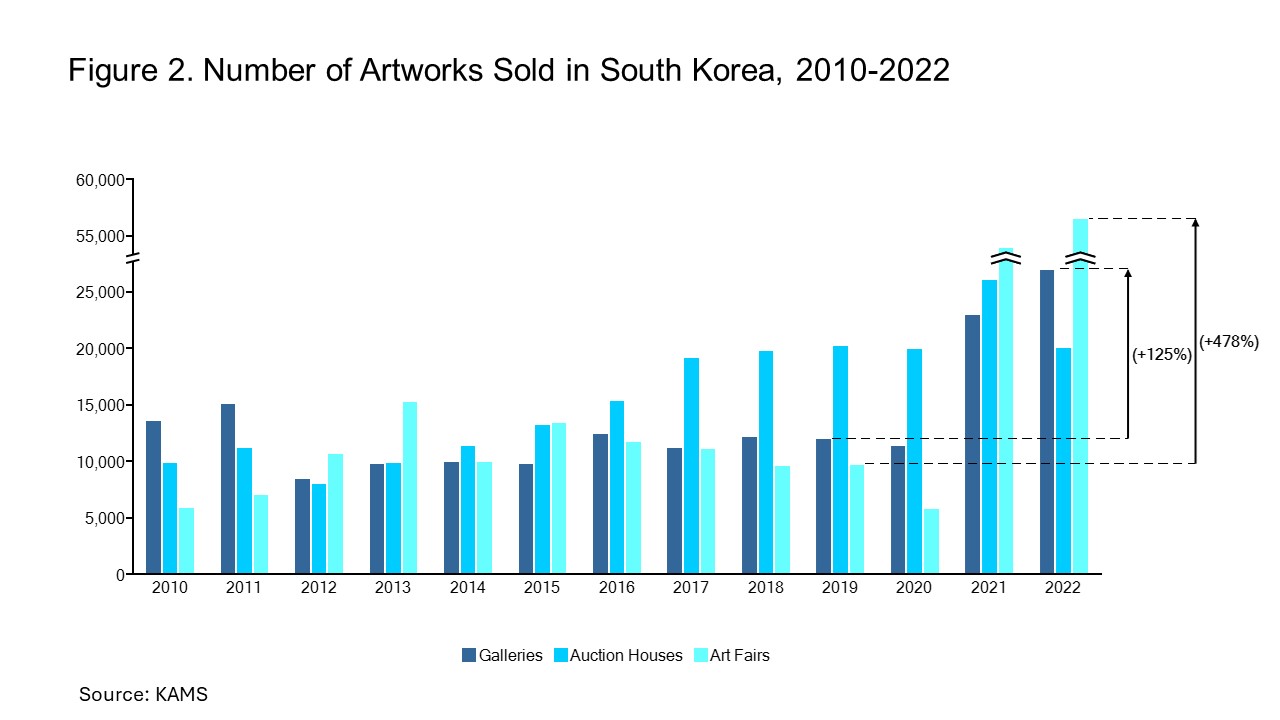

The South Korean art market (766 million USD in 2022) is still a fraction of the scale of markets in the United States (30 billion USD in 2023), China (12.2 billion USD in 2023), the United Kingdom (10.9 billion USD in 2023), and France (4.6 billion USD in 2023), but there are reasons to remain optimistic about its potential. In 2022, more than 103,000 artworks were sold in South Korea, which was more than double the number sold in 2019 (Figure 2).

The total sales revenue of the Korean art market topped the 1 trillion KRW (roughly 870 million USD) mark in 2022 from a more modest 380 billion KRW in 2019. Nearly 70 percent of this gain came from the purchase of artwork in galleries (45 percent) and art fairs (25 percent)—however, auction houses were also very active. From 2022 to 2023, South Korea ranked seventh in the world on contemporary art auction turnover after the United States, China, the United Kingdom, France, Japan, and Germany.

Upside Growth Potential

Prevailing trends in visitor traffic also support the growth narrative. Attendance at gallery exhibits increased by 122 percent between 2019 (1,259,467) and 2022 (2,793,801), while visitors to art fairs grew by 60 percent (627,256 to 1,001,796) during the same period. At the same time, visitors to larger museum exhibits declined from 20 million in 2019 to 19.6 million in 2022. This pattern may not be surprising given the number of galleries and art fairs that have recently entered the scene. For instance, approximately 60 percent of all galleries in Korea grossed less than 30 million KRW in 2022, compared to approximately 48 percent in 2021.

The above data also shows that individual spending on art in South Korea is not concentrated in the high end of the price spectrum. Recent research shows that the MZ Generation makes up about 50 percent of the revenue base and has the potential to be as high as 69 percent. Although a similar trend can be observed in other countries, the concentration of demand in this age category is higher in South Korea compared to other Asian countries by 10 to 20 percent.

Reasons for the Growing Interest

This is not to suggest, however, that art in South Korea is cheap by any standards. Lee Ufan, for instance, fetched a record-setting 2.7 million USD (3.1 billion KRW) for his piece at the Seoul Auction in August 2021. Two months before, another one of Lee’s paintings sold for 1.9 million USD (2.2 billion KRW). Although these figures can fluctuate depending on market conditions, one of the reasons for the growing interest is the relative return on investment. As an asset class, art can be a good investment option in Korea, where real estate is considered too expensive, and the stock market appears too risky. Investing in art can help diversify one’s portfolio and may even outperform other asset classes.

Financial considerations associated with South Korea’s unique tax structure also create an added incentive for potential buyers. In the United States, for instance, artwork is generally considered to be a capital asset and is subject to a 28 percent capital gains tax with an additional 3.8 percent Net Investment Income Tax (NIIT) for high-income earners. In South Korea, however, art pieces valued below 60 million KRW are exempt from the capital gains tax. For items above that level, a 22 percent tax is levied on a maximum of 20 percent of the sales price. No tax is levied on transactions involving works by living local artists, and works by living artists valued at less than 60 million KRW also enjoy Value Added Tax (VAT) exemption. Finally, all “unique” imported artworks are also VAT exempt.

The South Korean government’s continued public support has also been a force multiplier. Earlier this year, for instance, the MCST announced that it earmarked 1.75 trillion KRW to elevate Korea’s position in the global content market. Even though global demand was weak this year, the number of art fairs has increased to around 100 nationwide—thanks, in large part, to the MCST’s policy of promoting a “collaborative art ecosystem.” This past summer, the government also loosened restrictions on exports of art pieces made after 1946 by implementing the Art Promotion Act, which guarantees resale royalties for artists and warranties on artwork purchases for buyers.

More businesses are also looking to South Korea as a preferred base of operation in the region as censorship and crackdown on freedom of expression have become more common in China. This is especially true as of March this year when the Hong Kong legislature approved and put into effect the National Security Law that Beijing announced four years ago. While China is still an important market for art, galleries appear to be following this trend. For instance, the renowned Levy Gorvy Dayan announced this July that they would close shop in Hong Kong, while other galleries like the Peres Project and Duarte Sequeira have expanded their operations in Seoul.

Major events such as Frieze Seoul, Busan Annual Market of Art (BAMA), and Korea International Art Fair (KIAF) have also nudged a growing number of internationally recognized galleries, including Lehman Maupin, Pace, Perrotin, and White Cube, to throw their hats into the ring. Private capital injection by corporate players like Samsung and Hyundai also helps to broaden participation. Sotheby’s notes that South Korea ranks third among countries with the most private museums in the world, after the United States and Germany.

South Korea’s Emergence as an Art Hub

Money, however, is only part of the story. Without significant foundational content, it would be challenging to justify Korea as a global destination for art. South Korea seems to have a way of tapping into the global appetite for popular music, films, and food. It has now quietly built a broad and solid base of support for artists like Lee Ufan, Kim Whan-Ki, Yoon Hyong-keun, Park Seo-Bo, Suh Do Ho, and Koo Bohnchang—to name a few. In sum, the Korean art market sits at the intersection of culture, values, society, and politics. The right mix of these elements has created an ideal condition for South Korea’s emergence as an art hub. Events like Frieze Seoul serve as evidence of this emerging trend.

Dr. Je Heon (James) Kim is the Interim Director at the Korea Economic Institute of America. The views expressed here are the author’s alone.

Photo from Shutterstock.

KEI is registered under the FARA as an agent of the Korea Institute for International Economic Policy, a public corporation established by the government of the Republic of Korea. Additional information is available at the Department of Justice, Washington, D.C.