The Peninsula

South Korea: A Catalyst for Fixing Laws on Undersea Cables

Time is running out regarding threats to the world’s undersea cables: The world needs to start acting, rather than just discussing the problem, since more attacks on this critical infrastructure are happening in reality. South Korea is well-positioned to become a leader in creating a new regime that regulates the undersea cable industry. As one of the world’s largest fiberoptic cable suppliers, South Korea possesses the expertise necessary to engage other countries and exert its influence in designing a new regime to protect undersea cables, which carry more than 99 percent of the world’s internet communications.

With effective international law holding the perpetrator state accountable still missing in 2024, the anticipated problem has become apparent. On February 7, 2024, Frank Gardner from BBC reported the Houthis’ posting of a plan by telegram to attack undersea cables connecting Europe and Asia in the Red Sea. Some have questioned whether the Houthis possess the capability to sabotage undersea cables. However, Bruce Jones from the Brookings Institution commented that even if the Houthis lack the capability, not owning submarines, Iran may assist the Houthis by providing assets.

This prediction became a reality within less than a month. It has been reported that four undersea cables linking Saudi Arabia and Djibouti were attacked on February 26, 2024, disrupting communications over the internet, causing delays and possible information leaks. Although some people say that the damage is not critical because an internet blackout did not happen, this does not mean that the damage experienced from this disruption is trivial, $10 trillion travel across the world via undersea cables every day.

Another country to watch is North Korea. It may gain access to the essential technology to sabotage undersea cables with assistance from China and Russia. One reason for South Korea to seek changes to improve the law would be to build a mechanism with which to counter North Korea’s efforts to become an asymmetric power.

South Korea alone invested $700 billion between 2008 and 2023 to build its undersea-cable infrastructure, led by LS Cable & System, its largest cable company. In August 2023, LS Cable announced it would invest $117.5 million in manufacturing undersea cables to meet the increased market demand for cables carrying data for email, bank transfers across the seas, and more. Sabotage on those cables puts all users in danger of losing access to the internet, data being hacked or leaked.

Even during the COVID-19 pandemic, LS Cable signed contracts for undersea cables with the Netherlands, the United States, Singapore, and Bahrain. Positioning the country as a focal point in the undersea cable industry should foster more interest and discussion from the South Korean government. South Korea can act as a catalyst in organizations, such as the International Maritime Organization (IMO) and UN for example, by leading discussions on developing an international regulatory regime.

If North Korea physically attacks South Korea’s undersea cables, internet transactions are likely to halt. This won’t just mean extreme inconvenience to online shoppers and bank traders, and physical severing is not the only risk. Should North Korea tap into the cables, it could cause a leak of sensitive information such as health records and emails. North Korea has already demonstrated a willingness to attack South Korea’s digital infrastructure through hacking, and this would provide it another tool in this space, which is also seen as potentially below the threshold for kinetic response.

Attacking undersea cables could be a less costly option because attribution of undersea acts is difficult and takes time. It would be easier for North Korea to evade blame, even though conducting a kinetic attack on undersea cables would be considered a wrongful act in the eyes of international law. Undersea cables are a public good insofar as the deep seabed is part of mankind’s common heritage. This places undersea cables in the global commons. Therefore, these cables are placed under customs and practices governing the high seas, limiting jurisdiction by states and their vessels except in specific circumstances.

South Korea can share its vision for developing international law on protecting undersea cables in two places. One place is the International Telecommunication Union (ITU), which can contribute to developing international law, for example, by promoting commitment to protecting undersea cables. This builds on the ITU’s idea from its 2010 publication to utilize undersea communication cables for multiple purposes, not just to deliver data but also to monitor climate change. At the ITU, South Korea can champion the broader uses of cables as one reason it is appropriate to call an undersea communication cable a public good.

Providing better protection for undersea communication cables can even be discussed at the UN General Assembly. Since undersea cables can be utilized for a common purpose to monitor climate change, it is essential that they are protected better than the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) currently does. South Korea can propose a UN General Assembly resolution to protect undersea communication cables better, thus recognizing their importance as a public good.

Another venue where South Korea can play a part is in the IMO. An intergovernmental organization’s role is to set agendas and encourage states to help craft international norms. The IMO’s previous secretary general, who finished his term in December 2023, was Kitack Lim from South Korea. The fact that a South Korean government official held that position for eight years indicates that South Korea cared deeply about maritime security.

In the past, there were discussions about how to protect undersea cables better from the technician’s point of view, utilizing IMO rules. Changes were made regarding how to fix cables that had been cut. However, until recently, attention had not been paid to jurisdictional issues. South Korea could initiate reforms now to IMO rules and regulations from a legal perspective and is in a good position to serve as a catalyst in developing an international norm to regulate undersea cables.

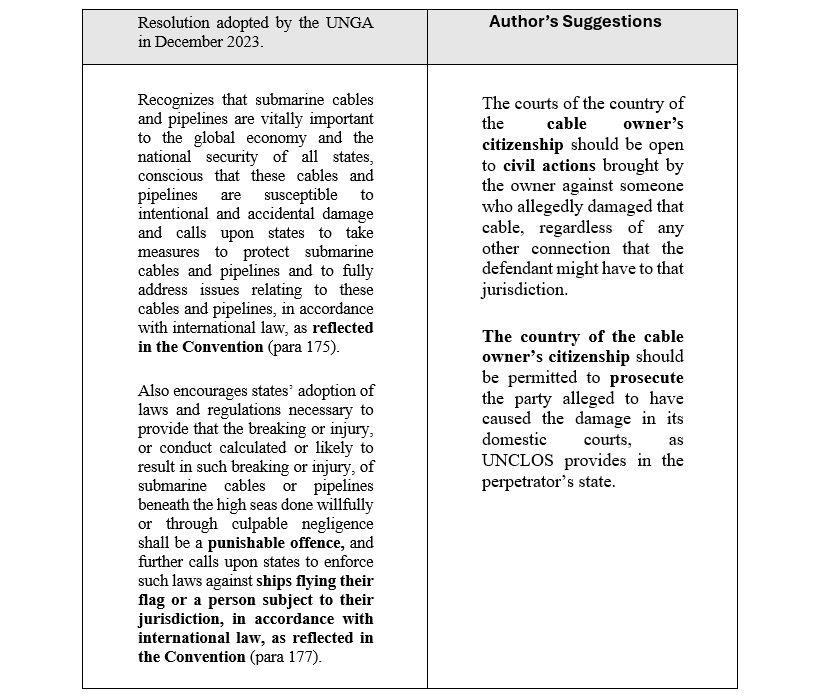

Another concrete step South Korea can take is to make changes through the UN. The UN “General Assembly(UNGA) Resolution on Oceans and the Law of the Sea” was published in 2023 but does not contain any substantial change in jurisdiction when undersea cables are sabotaged; it repeats what was previously stated in UNCLOS, as Figure 1 shows. South Korea can suggest changing the language to better protect undersea cables by substituting the author’s suggestions listed in the right column of Figure 1 for the current language.

Figure 1. The author’s suggestion to revise the provisions in the 2023 UNGA Resolution on Oceans and Law of the Sea

The suggestions provided above would establish a regime that not only punishes those who sabotage undersea cables after the fact, but would create a deterrence mechanism to reduce the risk of such misbehavior. First, the availability of a civil remedy is made explicit, compared to the UNGA resolution; the language suggested above for revision is more specific.

Second, in UNCLOS Article 113, the jurisdiction to hear civil and criminal cases involving physical cable attacks lies with either the nationality of those manning the ship or the court of the flag state, meaning the country whose flag is flying on the ship. In either case, the jurisdiction lies in the court of the attacker, not the court of the victim, where it should be. Permitting prosecution in the jurisdiction of the undersea communication cable owner, in addition to that of the perpetrator, would also have deterrent effects, so that undersea cables are less likely to be destroyed intentionally.

Since the 2023 UNGA Resolution lacks new ideas about jurisdiction, not going beyond what was stated in UNCLOS, it might appear that no progress was made toward developing international law regarding undersea cables. However, that was likely because, despite the existence of UNCLOS, states gathered at UNGA and reiterated the following, as previously stated in UNCLOS: “Every State shall adopt the laws and regulations necessary to provide that the breaking or injury by a ship flying its flag or by a person subject to its jurisdiction of a submarine cable beneath the high seas (international water) done willfully or through culpable negligence…shall be a punishable offence.” This implies that undersea cables are being sabotaged more frequently than is being recognized by the media.

This is probably why many states at the UN General Assembly felt the need to rewrite the UNCLOS clauses in the 2023 UNGA Resolution on Oceans and Law of the Sea, to warn perpetrator states they are violating existing international law.

When the 2023 resolution was being voted on, the only country that was against it was Türkiye. Their argument was that they don’t believe in universal law. Therefore, just bringing this up at UNGA level is a step forward that encourages further discussions.

Doing this at the UN and having states pass a more concrete resolution could add more pressure on potentially responsible states, posing a deterrent effect to discourage them from destroying undersea communication cables in international water. It is regretful that international law to better protect undersea cables has not been sufficiently revised as of 2024. The urgency of deterring attacks on undersea cables should be taken more seriously, inspiring South Korea and other Western states to prioritize better protecting our core infrastructure for internet communication.

Amy Paik is an Associate Research Fellow, who joined the Center for Security and Strategy at Korea Institute for Defense Analyses (KIDA). She has received various awards from both the US and ROK governments. In 2008, she received the Ambassador’s Appreciation Award from the State Department and in 2014 she won the Minister Commendation from ROK Ministry of Defense. The views expressed here are the author’s alone.

Photo from Shutterstock.