The Peninsula

Sanctions, Useful Tools for Changing North Korea—Lets Work Them, Carefully

By William Brown

New data shows North Korea’s imports of agricultural consumer goods from China, generally sold in markets, are holding up well in contrast to plummeting imports of investment goods procured by and for the state. This may be helping Kim control inflation and supports the won but carries ominous implications for the future of his socialist command economy. With a little perseverance, and continued help from China, we might pull him away from nukes and socialism.

The Hanoi summit brings into sharp focus the role of the UN and bilateral sanctions on North Korea, as does the new annual report of the Panel of Experts. They beg the question. Are sanctions working? Pundits of all stripes in Washington have differing views; some use the Hanoi Summit walk-away to insist they are not and assert the U.S. should return to “maximum pressure” even without further provocation [CNN commentator Max Boot]. Others see sanctions as valuable but want to trade them incrementally, tit-for-tat, for North Korean denuclearization moves [Washington Post editorial board]. And still others think the sanctions have done their job and want to accept Kim Jung-un’s latest gambit, trading most of them for, another, take-down of the Yongbyon nuclear facility [former negotiator Ambassador Chris Hill]. A common denominator, however, is none of these views seem to look closely at the impact sanctions are having on North Korea’s economy. Are they bringing useful pressure on Kim and, if so, in what ways? Pressure to do what? It’s complex and difficult to know but ultimately these are the all-important questions that U.S., South Korean, and UNSC policymakers must address.

Most perplexing is the Panel of Experts report itself. The panel does an outstanding job of ferreting out breeches in the sanction’s regime, especially with respect to “ship-to-ship” imports of petroleum products, allowing, it suggests, North Korea to bring in much more than the 500,000 barrels per-year UN Security Council cap allows. (This is on top of the legally acquired 3,500,000 bbl.[i] of crude oil provided each year as aid from China.) And it gives evidence of member state imports of prohibited North Korean anthracite, with corrupt buyers, even in South Korea, taking advantage of low prices offered by the North Koreans. This is important work and needs to continue, applying political and legal pressures on the violators. But at times the panel seems to be its own worst enemy. Just a week after Kim pleaded for sanctions relief in Hanoi, the Panel, in the first paragraph, declares “These violations render the recent UN sanctions ineffective by flouting the caps on the import of petroleum products and crude oil by the DPRK as well as the coal ban, imposed by the Security Council in response to the country’s unprecedented nuclear and missile testing.“

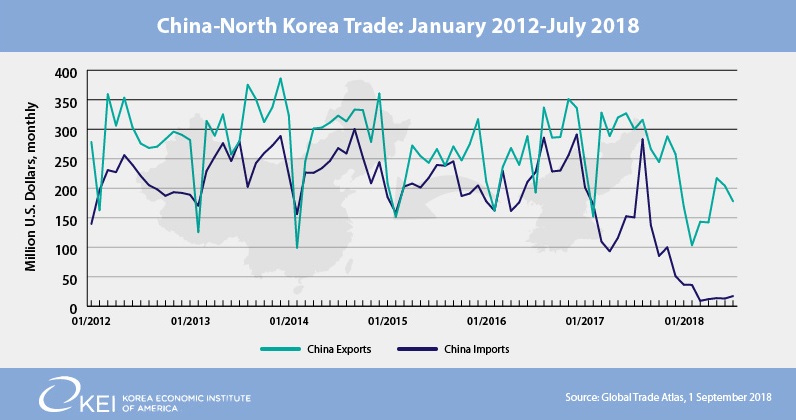

Are the sanctions thus “ineffective”? Perhaps it’s just an overstatement in a report focused on a laundry list of interesting smuggling activities; after all the testing has stopped and Kim Jong-un is engaged in unprecedented summitry to get sanctions lifted. But, inexplicably, nothing in the 300-page paper points to the official UN trade data that shows customs authorities in each member state reporting a near shutdown in imports from North Korea and a severe drop in exports to that state, just in the last eighteen months since the tougher sanctions were imposed. [ii] Data from China is shown above but it is true of all other UN members as well. Almost no trade. No indication in the report is given as to how such official data, if it is to be faulted, should be adjusted to reflect the smuggling and the real world of North Korea’s trade and finance that the Panel has discovered.[iii]

Certainly, there are puzzles that need to be worked out and explained. Did China really sell only 20trucks to North Korea last year, and no machinery or spare parts, as its customs data say? And why if indeed the world’s, and especially Chinese, customs officials are not lying on a massive scale, do we not see a commensurate impact on Kim’s economy, especially as we can observe stability in the won-dollar exchange rate and in other key prices? Wouldn’t a sudden collapse in exports and a smaller drop in imports shock the economy’s price structure and cause panic selling of the won? Prices of imported goods should soar while prices of exported goods should fall. Perhaps not in an orthodox communist country, where the government produces and distributes according to plan and money and prices have no real meaning.

In today’s North Korea, however, that explanation holds no water. It is obvious that Pyongyang no longer runs a communist economy in that orthodox sense and use of money is pervasive. The centralized plan and its fixed price and rationing system is likely working for only a small minority of its people. It’s now a dual economy, and a partially dollarized one. The official exchange rate, used to guide the plan, is about 130 won per U.S. dollar but only foreign diplomats pay attention; everyone else uses a market rate of about 8,000 won per dollar. Typical wages for the millions of state workers are about 3,500 won per month, with rations that are supposed to give them food and other necessities at highly subsidized prices; while market wages for millions of others range around 350,000 won per month, 100 times more, but without the cheap rations, and still are less than $50 a month at market prices. As the state has had difficulty supplying rationed products over the years, and as the distribution of essentially free food, housing, electricity, education, and medical services has crumbled, state workers, including Workers Party officials and the military are privatizing their work activities in a slow but steady erosion of the socialist state.

In this odd mix of an economy, with liberal use of U.S. dollars and market forces operating side-by-side a fixed-price rationed economy, run by the state, Kim Jong-un early in his administration was able to get inflation under control and stabilize the won, pegging it at close to an 8,000 won-to-dollar rate, something his father was never able to do.[iv] Bringing this monetary stability is no doubt a remarkable achievement, especially over the course of the last two years as Chinese sanctions began to bite, cutting off virtually all the country’s exports and presumably causing an outflow of dollars needed to pay for essential imports. Even if the trade data is drastically falsified, widespread publicity over Chinese official actions to halt purchases of North Korean products should have been enough to cause a run on the won, or one would think.

There are several possible explanations, but for me only one makes a lot of sense. It is in accord with standard macroeconomic theory and is not novel but, for Pyongyang, may be embarrassingly capitalistic in nature. I suspect that won stability and suppression of inflation is maintained by severely curbing won credit and printing of won currency–what we in the U.S. would call an extremely tight Federal Reserve policy aimed at protecting the dollar and stopping inflation yet carrying a high risk of recession. A shortage of won, both cash and credit, thus keeps it valuable relative to equally short U.S. dollars. If dollars leave to buy imports from China, won loans have to be called in from the state enterprises, which then must make do by trying to sell some of their products privately, rather than contributing them to the plan; by squeezing worker pay; and by foregoing investment and maintenance. And the authorities, by employing a pegged mechanism, which they must defend by selling dollars and buying won as needed to stymie outbursts of speculation, over time they build public credibility and market interventions become less necessary. This, by itself, might not protect the won, given the interest rate tool is generally not available in the socialist system, but, ironically, the wide availability of U.S. currency gives even the average North Korean citizen a sound financial savings vehicle, perhaps stored under mattresses, taking money out of circulation. I expect, if it could be measured, we would see private savings soaring in the last few years, taking out inflation with it. Such real savings are great for the public, offering some recourse against a vile government that in theory doesn’t allow private ownership of capital, but must be concerning to the state which must feel it is losing economic and even social control.

The system is thus not too dissimilar from Hong Kong’s currency board mechanism, which employs a dollar peg supported by a monetary policy that allows an increase in the HK dollar money supply only as U.S. dollar reserves are increased. If Hong Kong’s current or capital account falls into deficit, its money supply contracts automatically, interest rates rise, government spending falls, and imports plummet, resolving the imbalance all without a change in the exchange rate. I expect it is the same in Kim’s brave new North Korea, ironically mimicking one of the most liberal monetary systems imaginable.

The implications for the domestic economy of such a policy should be profound, especially given the state still directly or indirectly employs probably half the labor force. Most importantly, the inability to print currency or extend credit puts pressure on a state budget that has long been a meaningless accounting exercise. An analogy might be made to a U.S. state, which after a long bout of borrowing finds it can no longer roll over its debts. Unable to create money in our federated system, the state then must slash expenditures or raise taxes, establishing a surplus that it can use to repay debt.

Direct evidence of such budget tension is hard to come by but given our incomplete understanding of the country’s finance, this should not be a surprise. Several recent hints have cast some light and suggest that Kim’s government is feeling a growing budget constraint of this kind, the indirect result of the current account deficit and thus of sanctions. Citizens interviewed by Daily North Korea, for instance, increasingly complain of a lack of money in the system, not increased prices. Apartment lease prices are said to be falling. And everywhere they complain about regime efforts to raise fees and collect more cash, either dollars or won. Citizens can now pay cash to get out of all kinds of normal socialist system community work requirements, and even from military conscription. Electricity meters are being installed in some apartments, suggesting an end to virtually free (and famously unreliable) power supply. And now we see complaints from a New York based North Korean diplomat who says food rations are being cut in half. Aid agencies are arguing this is the result of a weak harvest, but I find this a bit disingenuous. Market prices for rice and corn have been falling in recent months, an indication of deflation caused by tight money rather than rising as one would expect if a poor harvest was to blame. In depressed conditions, falling prices could occur even with decreased supply, but the inferior corn staple seems to have fallen more than rice, suggesting people are willing to trade calories for taste, a good sign. The more important point is that these markets are for ordinary people who procure grain privately and whose state provided rations long ago disappeared. A cut in food rations in 2019 thus probably means a cut for state employees, not the general public, and suggests the regime is unwilling or unable to purchase adequate grain from the collective farms, given its new budget constraints.

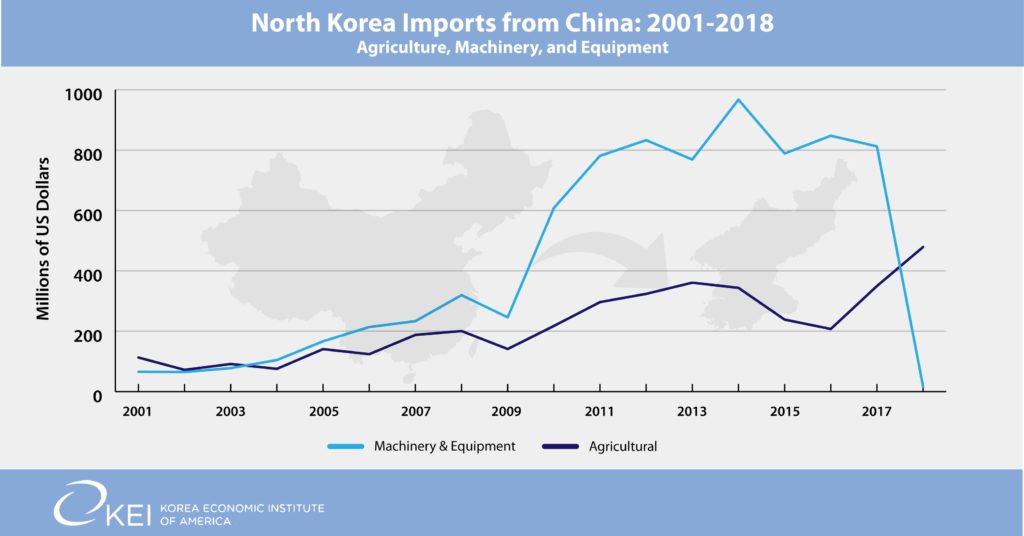

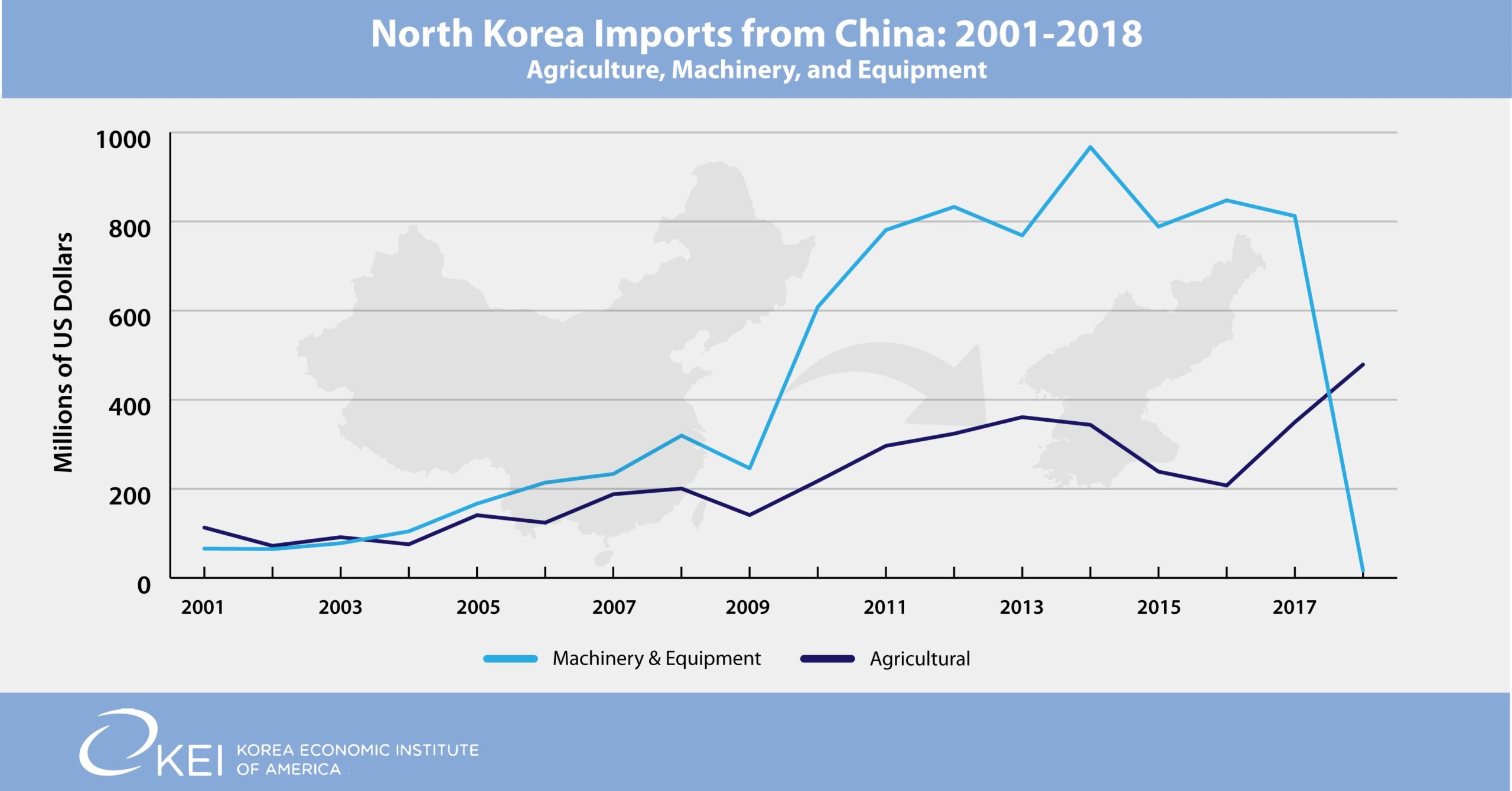

Budget issues also may also be showing up in trade data. The country’s exports have been hardest hit by sanctions but, with a lag, imports are now falling as well, down 33 percent in 2018 from China and down 5 percent in January from January a year ago. As shown in the table below, imports from China since 2017 by two aggregate commodity groups, agricultural and similar products sold to consumers in markets, and machinery and transportation equipment, the “means of production”, items purchased by state enterprises and the government itself.[v] The former have held up well, increasingly steadily during the sanction’s era and even last year. But the latter have been decimated; a combination of general UN sanctions on exports of such goods to North Korea and, likely, a decline in foreign exchange available to make such purchases. This indicates the state’s budget for capital equipment is likely being slashed to the core, spelling big trouble for Kim’s economic growth program while alleviating short term pressure on the won and on prices. But the commodity detail shows not only are investment goods slashed. Imports of intermediate production goods, such as spare parts for complex machinery, have been eliminated as well, squeezing to the bone enterprise managers called upon by Kim to increase output.

On his long train ride home from Hanoi, Kim is said by his deputy foreign minister to have grossed over why he even bothered to take the trip, given he got no relief from the sanctions. He reached out, gambling perhaps, that the smaller deals discussed in negotiations would not provide anything in the way of real relief for his budget problems, and asked for removal of virtually all economic sanctions. But he got nothing, and domestic pressures are sure to rise as a result. This is budget time in Pyongyang and the state, probably the hapless premier, will soon roll out its 2019 budget, always in the past a dull affair, rubber stamped by the hand-picked legislature and amazingly devoid of numbers. But this year, at least behind the scenes, I suspect it might be a little different.

Sanctions look to me like they are biting. But they should not be forever. Our question is can they be wiggled like a wrench back and forth to get what we need from Kim, not only on nuclear issues but economic reforms as well.

William Brown is a non-resident scholar at KEIA and teaches at Georgetown University and UMUC. This and other related postings can be found on his website, NAEIA.com

Graphics by Juni Kim, Program Manager at KEI.

UN image from zhrefch’s photostream on flickr Creative Commons.

[i] China is assumed to provide 500,000 tons of crude oil a year by pipeline on a long-term zero-interest loan agreement, which Pyongyang never repays. This corresponds to about 3,500,000 million bbl. for Daqing quality crude, as we assume to be the case. North Korea is able to refine the crude into about an equivalent mix of petroleum products.

[ii] See Global Trade Atlas or any trade data aggregator, or the UN’s own data.

[iii] One of the largest inflows citied is from cybercurrency hacking. …

[iv] Some argue the won is pegged to RMB, not the dollar, but since the dollar and RMB have been relatively stable against each other, it hasn’t made much difference. Large transactions are usually made in dollars, market transactions in RMB. Government transactions are likely still largely in won.

[v] Cell phones also are included as machinery in the antiquated UN trade nomenclature, and these were large until officially falling to zero, last year.