The Peninsula

Price Movements Suggest Volatile Food and Fuel Markets in North Korea

By William Brown

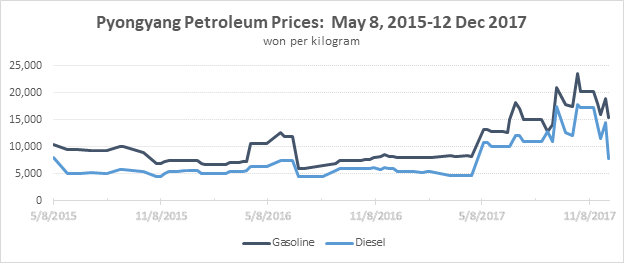

In previous blogs we have looked at several anomalies in market and foreign trade data related to North Korea, including the crude oil situation and the won exchange rate. In the former, we conjecture that China’s government has simply put crude oil “off the books” since January 2014 and that the flow continues in its normal pattern despite zeros shown in its custom bureau’s monthly data. No good explanation is available—all exports are supposed to be counted and if not, China’s overall trade and balance of payments statistics, even its energy use data and national accounts data, i.e. its GDP, is likely corrupted. So, this decision must have been made at the highest levels, possibly to put pressure on the Pyongyang regime, a veiled suggestion perhaps that it should not take the gift of crude oil for granted. The other issue, of even more importance, is the continuing stability of the North Korean won against the U.S. dollar in informal trading markets despite a sharp deterioration in North Korean export earnings as reported by its trade partners. This speaks to the success the Kim regime has made in handling overall inflation and somehow controlling money changers who one would suspect are anxious to trade won for dollars every time a new rocket is fired, and more sanctions imposed. The informal market rate as of December 11, according to Daily North Korea, was 8,005 won per dollar, an appreciation of 6 percent over the past two years. Still, the tough sanctions on North Korean exports are just now really coming into play so this bears close watch. Other prices are volatile, moving up and down in big jumps, suggestive of active but thin markets. In Pyongyang, over the two years to 11 December:

Domestically produced goods have tended to fall in price:

- Rice prices experience 50 percent swings but are the most stable, ending 2 percent lower.

- Corn prices fluctuated wildly and also ended up with little change.

- Pork prices rose 25 percent.

Imported prices have risen, suggestive of a sanctions impact, although they have fallen in recent weeks.

- Gasoline prices more than doubled, up 110 percent.

- Diesel prices rose 48 percent, even after falling sharply last week.

Food and fuel no doubt are two of the most important products traded in North Korea’s relatively new markets; indeed, they are so important, government attention and regulation should be expected, and transactions constrained in some ways. Gasoline, for instance, still requires a coupon but the coupons can apparently legally be bought and sold, unlike normal ration tickets. Defector surveys indicate that only about a fourth of household food supply now comes from rations with the remainder purchased on the market. These markets may be capped, or prices otherwise constrained by the government, but they seem to be telling a story that forces of supply and demand are in operation and that the government is not interfering too much, allowing prices about like those in China and many times what can be afforded in the state’s controlled system of wages and benefits.[i] Whether this is a matter of deliberate policy or a loss of state control over production and distribution is an important ongoing question.

- We have little information on what is occurring with wages. State wages appear to remain incredibly low, with the government facing a large budget constraint, but private wages are likely rising, reflecting market activities and rising private productivity.

- We also have no gauge of housing and other larger capital goods cost indicators. These are often priced in US dollars. Modern technical products, like cell-phones, are priced similarly to what they are in China and are often purchased in dollars or RMB.

Rice and Corn—a spring drought, apparently now resolved

Conflicting information this winter is apparent with respect to North Korea’s perennial food problems. The FAO reported a potential major food shortage this summer based upon drought conditions, and recent alarming reports of dead fishermen, washing up on the Japanese coast, suggest conditions may be worse than is commonly believed. Market conditions, on the other hand, provided by Daily NK’s weekly price reports, help round out this story.

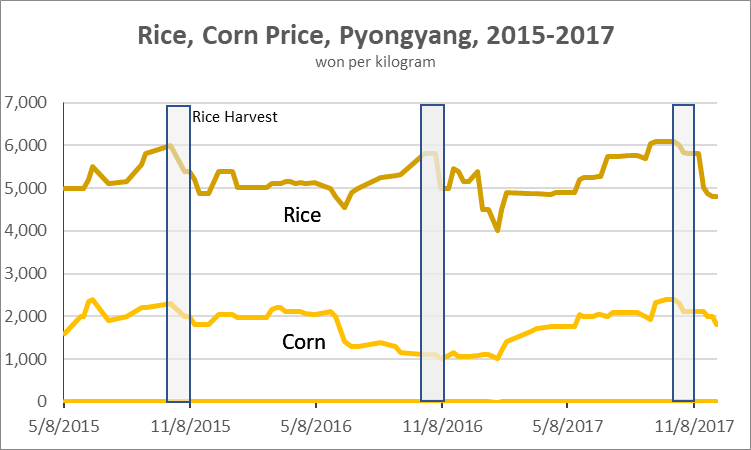

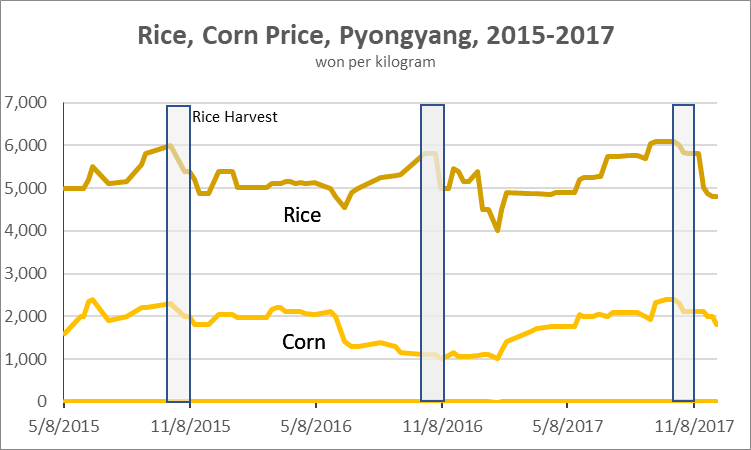

Source: Daily NK

These two commodities provide the huge bulk of North Korea’s food supply and weekly prices are available in three markets, Pyongyang, Sinuiju, and Hyesan, the latter two on the Chinese border. Moreover, the relative price between rice and corn is easily figured and is in some ways the most important indicator since it should give us an idea of whether overall food, that is calories, is in short supply. The two commodities are close substitutes, but rice is the preferred product, so it will always command a higher price. In times of food shortage, however, the price of corn should approach the price of rice since calorific quantity is more important than quantity or taste. In 1996, for example, during the famine, the price of corn rose to about 0.67 percent the price of rice and held above 0.5 percent until 2003 when market reforms started to revitalize agricultural production. North Korea’s socialist command system also fixes corn at half the price of rice in its rationing, as did earlier dynasties in Korean history. For comparison purposes, world prices put the price of corn at about a quarter that of rice.

A weak harvest in 2015 put pressure on food supply but, as the graphics suggest, supply must have improved substantially in 2016 with a good harvest and prices fell. Price trends correlated with drought conditions earlier this year and the price of corn doubled from unusually low levels, while rice increased modestly, raising concerns that the market was shifting toward the lower quality product. With the recent fall harvest, however, the situation seems to have normalized as both rice and corn prices have fallen. Seasonality, of course, is important so we also show price changes from year-earlier levels. This data, as of mid-December, shows no increasing tension in the food supply and suggests the summer price hike was less worrisome than first considered.

Interestingly, these North Korean prices are close to Chinese export prices, dominated in U.S. dollars and changed in North Korean won at the prevailing market exchange rate in North Korea.[ii] This suggests unconstrained, free trading, between China and North Korea for these commodities.

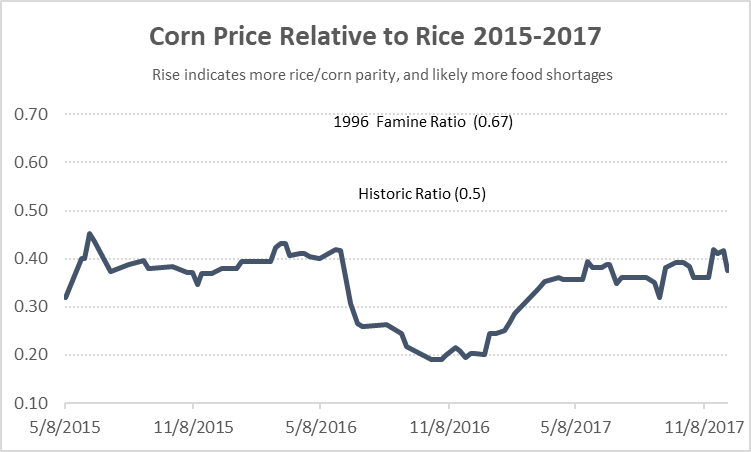

Foreign trade data may lag worries of famine, but it also suggests no unusual problems through this fall. Imports from China rose somewhat in mid-summer but were still small compared to past imports—in the 1990s and 2000s these averaged closer to 100,000 tons per month—and compared to total supply of several million tons. The largest volumes have been in processed flour, which possibly was purchased by international aid groups in China, reacting to the FAO and other reports. Imports from other countries has been minimal.

Source: Global Trade Atlas

Whereas this market and trade data thus seems reasonable, we need to be mindful that the sources are thin, and we can’t be sure the markets provided by Daily NK are representative, or that the regime might be able to falsify the information. Apparently, Pyongyang prohibits the UN aid agencies operating in North Korea from collecting or reporting market data, a significant hinderance in their ability to provide support without harming farmer’s interests.[iii] The famine in the mid-1990s was known as a “silent famine” since supplies varied substantially even between neighboring villages. The growth of markets, improved local transportation, and cell phones that guide merchants as to where to send their supplies, should be alleviating those concerns but there is little on the spot information to confirm that.

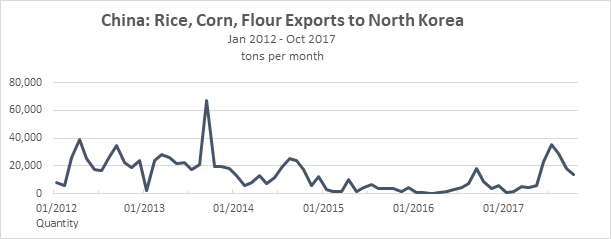

Fuel prices jump on foreign exchange shortages, sanctions, slip half-way back after crude oil is exempted.

As noted in our July blog, refined petroleum product prices in Pyongyang soared after Presidents Trump and Xi met in Florida in May and discussed severe sanctions on North Korea, and after Chinese newspaper articles suggested China might finally act to limit its supply. Prices continued to rise in erratic fashion through November, suggestive of hoarding, but have recently tapered off, with diesel falling sharply just last week. Domestic prices are still much higher than international prices, however, using the market exchange rate to convert won to dollars.

- Diesel’s W7,500 price per kilogram of 12 December is still expensive compared to the equivalent W5,200 per kilogram Chinese price.

- Even higher profits are available for gasoline, with Pyongyang prices of W15,400 per kilogram compared with Chinese prices of the equivalent of W4,225 per kilogram.

- Through May of this year, internal prices had held pretty steady, with gasoline rising slowly against diesel, and were generally consistent with Chinese prices. May marks a turning point.

Source: Daily NK

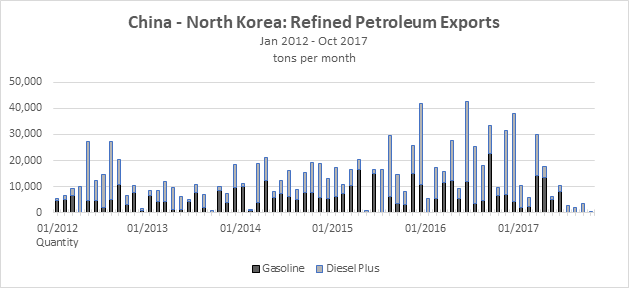

Reduced imports from China beginning in mid-summer of diesel and gasoline likely contributed to or even were the main cause for the rise in prices. Shipments of gasoline have been negligible since July and diesel has fallen to almost nothing. Media reports have suggested Russia has filled in some of the gap but, at least according to official Russian trade data through September, it supplies only about 1,000 tons per month. The price differential between domestic North Korean prices and international prices, however, is large enough to induce much smuggling, for instance by ship to ship ocean transfer. More importantly, we assume China continues to supply about 50,000 tons per month of crude oil free of charge (600,000 tons per year) and this would be refined into a comparable volume of products, by far the largest source. Concerns that China might cut this supply may have helped boost prices in mid-year but, since the August and September UN sanctions only require no increase in crude shipments, concerns may have dissipated somewhat. The new sanctions require about a ten percent cut in refined products sales to North Korea, to 500,000 barrels (about 70,000 tons) a quarter beginning last October or 23,000 tons per month). Imports from China in October, at least, were far below that rate, leaving room for an increase in November and December.

William Brown is an Adjunct Professor at the Georgetown University School of Foreign Service and a Non-Resident Fellow at the Korea Economic Institute of America. He is retired from the federal government. The views expressed here are the author’s alone.

Photo from (stephan)’s photostream on flickr Creative Commons.

[i] State wages average about 3,000 won per month, enough to buy less than one kilogram of rice, but are supplemented by nearly free rations that in theory cover basic necessities.

[ii] For instance, in October, China’s FOB (excluding transportation) price of rice exported to North Korea was $618 per ton, or 4,933 NK won per kilogram, at the prevailing W8000/1 exchange rate. The Daily NK average for October was 6007 NK won per kilogram, in the markets.

[iii] The recent extensive FAO report on North Korea’s food situation, and its call for more aid, provides virtually no information on prices. In questioning, UN officials say North Korea does allow market type research to be reported.