The Peninsula

Power on Parade but Crisis at Home as North Korea’s Economy Wavers

Kim Jong Un is projecting confidence abroad, appearing alongside Xi Jinping and Vladimir Putin and flaunting his nuclear arsenal, but his regime faces mounting economic turmoil at home. The North Korean won has reportedly lost more than half its value in a year, inflation is surging, and new laws are struggling to force an increasingly market-driven population back into the socialist system. Chronic trade deficits, opaque revenue from arms sales and cyber theft, and the diversion of foreign currency into private hands are eroding state control. The contrast between Kim’s stagecraft in China and the economic reality in North Korea reveals a regime that remains politically resilient but economically brittle.

North Korea’s won, whose stability was the hallmark of Kim’s first eight years in power, is practically worthless, as the use of dollars is expanding, according to the two websites that most closely track exchange rate and price data, Daily NK and Asia Press International. Even Russian tourists visiting the new Wonsan-Kalma Beach Resort use U.S. currency. The state has been forced to raise wages by about ten times in the last year, but it is not keeping up with a vicious cycle that includes printing more cash while prices rise and currency falls. New laws are working to rein in market forces, work within the socialist system, despite below-subsistence-level income and a ration system that hasn’t worked for decades. Recent economic growth, however accurate those projections are or aren’t, from people launching out on their own—the new rules will not stop that because the party leaders need money to live as well.

Dollar–Won Exchange Rate

Daily NK reported an astonishing jump in the dollar-won exchange rate, from KPW 22,000 to 40,000 during Kim’s two-week trip to China. It then shows the dollar-won exchange rate dropping back to KPW 32,000. While the reason for the turbulence is not yet clear, the won is still less than half its value from a year ago. Asia Press, whose data normally tracks well with Daily NK—they both claim that they obtain their data by phone calls to sources from different locations inside North Korea—shows a steady rise in the dollar-won exchange rate to KPW 29,000 per dollar by the end of September, partially mending the discrepancy with Daily NK. U.S. and South Korean intelligence agencies may be able to confirm or deny the veracity of this data, but are mum on the issue.

Source: Asia Press | Note: An increase in the North Korean won to the U.S. dollar represents a depreciation of the North Korean won as measured by the U.S. dollar.

Either way, the figures must be concerning Kim and raise questions about the regime’s ability to control internal money flows and foreign funds that may be flowing into private pockets—beyond the purview of the central bank—from overseas remittances, for example, to cyber theft. In a banking reform initiative in 2015, soon after coming to power, Kim promised he would stabilize the won and that inflation, the bane of capitalist countries, would be no more. To do that, he liberalized the banking system, allowing the use of capitalist tools but without private ownership of capital to garner trust in the won. But corruption grew, and in 2025, it’s unclear whether Kim’s earlier reforms have generated any lasting change.

Price of Rice and Corn

Most prices have reportedly increased by double digits, but this inflation is most visible in the price of rice, which has risen from KPW 6,800 per kilogram to KPW 12,500 in the last twelve months—a 68 percent jump, according to Asia Press. Daily NK puts the current price at KPW 21,000, triple the cost of a year ago. Corn, the preferred staple for the North Korean masses, has been more stable, suggesting famine is not yet in the air. It traditionally sells at half the price of rice per kilogram, and it is now only one quarter, indicating a good trade-off. Moreover, it seems North Korea will escape 2025 without the usual weather catastrophes, and the harvest is well underway.

Kim has worked to decentralize industries and give more authority to locally owned companies, which may be helping to placate the provinces even as it raises the specter of a loss of central control. But it would also likely make prices diverge across provinces, given the weakness of the country’s transportation infrastructure, so pockets of famine are possible.

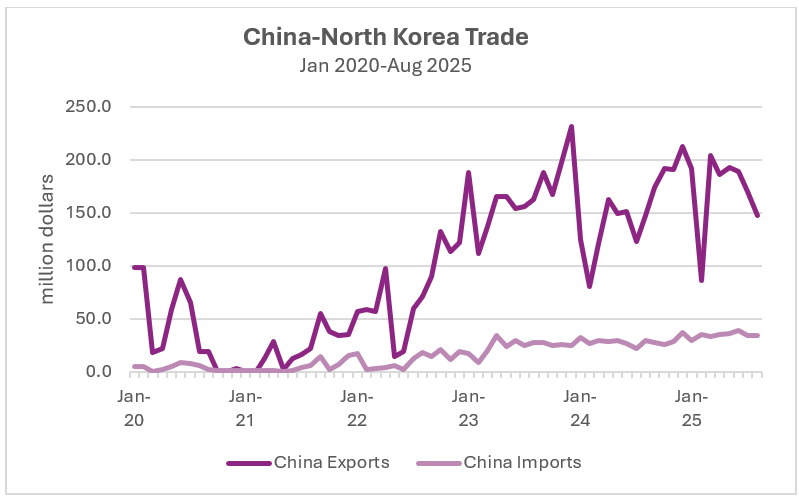

Plenty of Imports, Too Few Exports

Source: General Administration of Customs of China

Official data released by the country’s few trade partners, mainly China, show a slowing growth in exports to North Korea and no real effort by the North Korean government to address the large trade imbalance by raising its own exports. South Korea’s Bank of Korea (BOK), along with some media outlets, like to point to certain instances of large export increases, but these are from a tiny base and do not reflect an urgency to stem the external financial crisis. More than ever, there are questions about North Korea’s balance of payments. China purports to follow UN Security Council resolutions, but its data clearly misrepresent actual trade, undercounting, for example, North Korean imports of machinery and energy items, especially petroleum, and its own imports of North Korean coal.

Meanwhile, there remains a complete blank on how much North Korea is earning from its involvement in Russia’s war in Ukraine. Millions of artillery shells and thousands of soldiers could be earning up to several billions of dollars, but nothing is publicly known about the deals, nor whether North Korea is spending the earnings on high-tech Russian military equipment that it needs to engage a rapidly improving South Korean military. Or whether these are just gifts to buy some sense of solidarity with a great power. Adding to the unknown is how much North Korea earns from its cyber thefts, though estimates peg this at at least USD 6 billion since 2017.

Whatever the foreign balance is, the fact of won debasement and soaring prices strongly suggests that for North Korea’s central bank, foreign income or borrowings is not enough. Some of the earnings and remittances may be going into private pockets, staying in dollars, yuan, or even cryptocurrency outside the control of the state—a scary thought for Kim Jong Un. He executed his aunt’s powerful husband in 2013 for, among other “capitalist crimes,” storing away EUR 4.6 million. A decade later, such private funds are likely to be much greater.

Bank of Korea’s GDP Proxy

Around the time of Kim’s Beijing trip, South Korea’s central bank reported that North Korea’s GDP grew 3.7 percent in 2024, its “fastest pace in eight years.” There may be some truth to these projections, but there are severe limits to creating complex national accounting data for a country with a non-market economic system that does not release its own accounting work. Accuracy and growth rate aside, the GDP estimates still imply that North Korea only produces a mere thirteenth of what South Korea does and likely consumes much less than that, given their high military and government expenditures. Surely, that would put them well below the global extreme poverty level, which the World Bank estimates at USD 2.15 per day.

As the BOK itself emphasizes, the series began thirty years ago when it was tasked to compare the production of various goods across the two economies. Iron versus iron, rice versus rice. This was a time when Pyongyang also published similar data. By now, these ratios are absurd, with South Korea’s production overwhelmingly large. The BOK report is full of other useful inter-Korean comparisons. The most interesting is its estimate of population growth, claiming that North Korea’s population grew only 0.4 percent in 2024, better, but not by much, than South Korea’s minuscule 0.07 percent.

This year, the report seems to be overly optimistic, discounting inflation, the devaluation of the won, and the huge trade deficit. Exports for the year are a highlight, rising 11 percent, but they still equal only two months of imports.

In conclusion, Kim’s bid to project strength abroad cannot conceal the scale of the economic crisis unfolding in North Korea. The regime has weathered adversity before, but today’s convergence of inflation, fiscal opacity, and decay poses a deeper, more structural challenge that could eventually constrain Kim’s options more severely than ever before.

William B. Brown is the principal of Northeast Asia Economics and Intelligence, Advisory LLC (NAEIA.com) and Non-Resident Distinguished Fellow at the Korea Economic Institute of America. The views expressed here are the author’s alone.

Photo from DPRK state media.

KEI is registered under the FARA as an agent of the Korea Institute for International Economic Policy, a public corporation established by the government of the Republic of Korea. Additional information is available at the Department of Justice, Washington, D.C.