The Peninsula

Port Strike Should Prompt Strategic Thinking on US Supply Chains and the Role of AI

The International Longshoremen’s Association (ILA) ended an East and Gulf Coast strike—its first strike since 1977—on October 3. Determined to receive substantial pay raises for workers, one of the ILA’s main points of contention was the role that automation may play in the industry as part of the overall progress in AI. Had it not abated, Reuters reported that it could have cost the US economy up to $5 billion a day. Shipping backlogs are expected to endure for another two to three weeks as a result of the strikes.

Disruptions to shipping caused by the COVID-19 pandemic and one-off events like the 2021 Suez Canal blockage or drought conditions in the Panama Canal have exposed the links between national economies and the vagaries of global maritime trade. The port strikes—yet one more event destabilizing international supply chains—should renew attention on economic security and collective efforts to promote stability in global commerce between the United States and its allies and partners. Additionally, it should foster greater consideration of the political and economic effects of new industrial systems resulting from the increasing use of AI. The risks to global trade, whether from strikes or other sources of disruption, are manifold.

Consider US economic relations with its trade partners in Asia, from which imports of semiconductors, auto parts, and strategic chemicals play a critical role in the US economy. Although most US imports from East Asia have historically been concentrated on West Coast ports, the expansion of the Panama Canal in 2016 and measures to deepen the capacity of ports along the East Coast in recent years have led the Eastern seaboard to assume an increasing share of imports from the region. This means that port closures on the East Coast—whether from walkouts or natural disasters—affect the United States’ trade with Asia, even as West Coast ports are separately unionized under the International Longshore Warehouse Union (ILWU) and not the ILA.

To illustrate, in anticipation of the strike and potential closures, companies had already been rerouting ships to the West Coast. In the future, labor strife or port closures due to other factors could mirror the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic when port jams in Los Angeles and Long Beach led to supply chain vulnerabilities across all aspects of US trade.

Take, for example, imported auto parts. In the leadup to the strike, Hyundai and Kia’s US auto parts inventory supplies for the month of August were at 77 days and 65 days, respectively. If the strike had persisted, such inventories would likely have been quickly depleted. Indeed, the 2020-2023 global chip shortage was in part exacerbated by the pandemic’s port backlogs, as facility shutdowns and temporary border closures caused critical shipment delays.

More strikes or closures would hit US trade with Korea hard. According to the Korea Trade Statistics Promotion Institute (accessed through KEI’s proprietary data), Korea exported $115.7 billion of goods to the United States in 2023, of which over $99 billion was transported by ship. Korea’s imports from the United States similarly saw roughly $45 billion out of a total of $71 billion arrive via maritime transport. Put simply, ocean shipping comprises the majority of overall US-Korea merchandise trade.

When thinking about potential future scenarios, the aftermath of Korea’s trucker strikes in 2022 provides a basis for comparison. The protests, occurring separately in June and October, drastically disrupted Korea’s shipbound port exports. In fact, Busan port’s container traffic was reduced by two-thirds, while some critical strategic goods—such as petrochemical products—saw daily shipment volumes reduced by up to 90 percent as a result of the temporary protests. Although driven more by concerns over fuel prices rather than automation, the June protests reportedly cost the Korean economy $1.2 billion as shipments were delayed. More thought should be given to how these protests might recur in light of advancements in AI, especially as the US strike leader has indicated his willingness to take the protests global.

All of this opens the door for a broader conversation about how AI-enabled systems will be received in the global economy and by the labor force that helps it operate. For now, the effects of the strikes may only be visible through increased backlogs in maritime trade, yet at the heart of the matter are the ongoing and rapidly evolving effects of new systems and technologies.

Tom Ramage is an Economic Policy Analyst at the Korea Economic Institute of America. The views expressed here are the author’s alone.

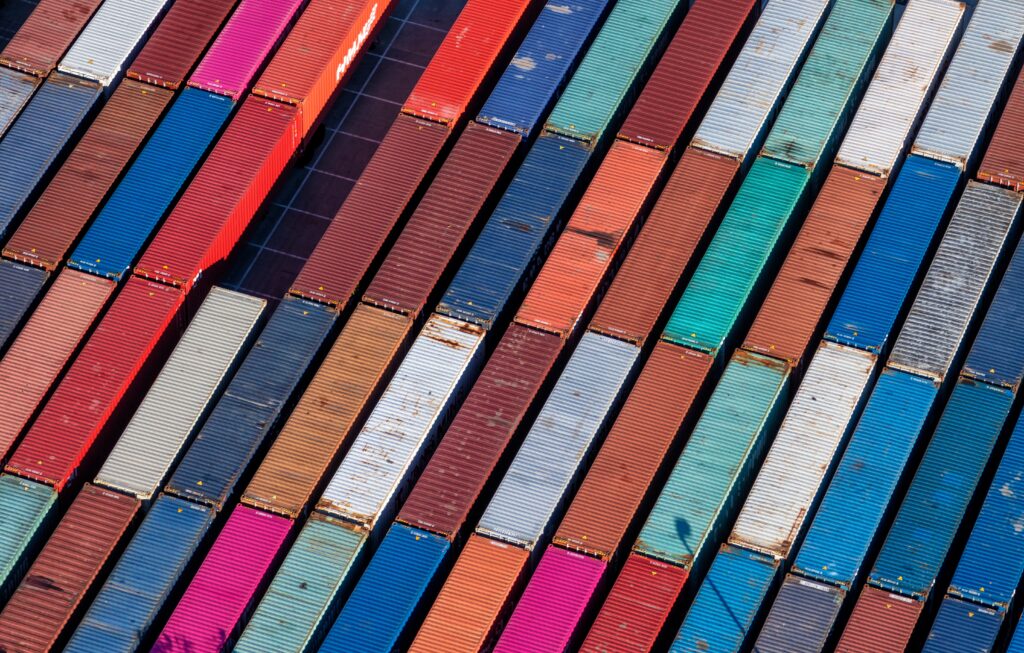

Photo from Shutterstock.

KEI is registered under the FARA as an agent of the Korea Institute for International Economic Policy, a public corporation established by the government of the Republic of Korea. Additional information is available at the Department of Justice, Washington, D.C.