The Peninsula

Plunge in Trade Impacting North Korean Prospects, Forcing Decisions

By William Brown

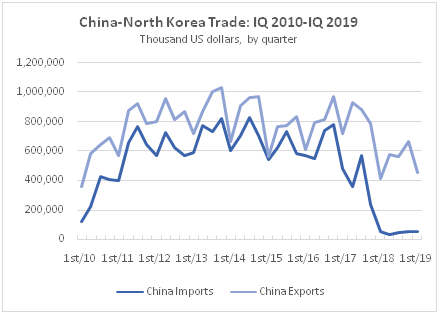

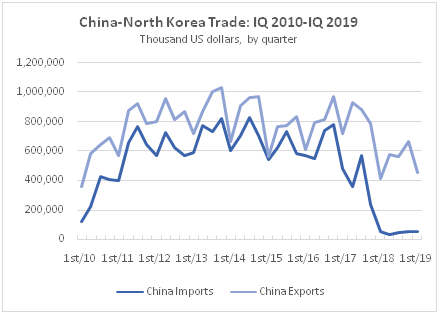

Many Asia specialists in Washington and elsewhere continue to think UN sanctions against North Korea are slipping and that without new resolutions or U.S. executive actions it is only a matter of time before economic pressure on the regime will ease up. This may be true and there is evidence of North Korean and Chinese firms adjusting and quickly shifting production and trade to the few categories yet unsanctioned. Anecdotes of smuggling—which naturally increase as legal trade falls off—are also widespread. But much of this misses the point. Not all trade has or will stop, and no one ever suggested that it should or could. For a country that trades so little anyway, and prides itself on its self-reliance, the trade that it does undertake is vital and even a small decline can be devastating, let alone something like the 50 percent drop in trade with China last year. Meanwhile, official data continue to indicate that extremely tough limits on trade remain in place by virtually all UN members. Political leaders in the most relevant countries, China, Russia, South Korea, Japan, and the EU continue to show no willingness to ease up despite pleas by Kim Jong-un to make at least humanitarian exceptions. And Kim’s summits with the leaders of China, South Korea, Russia, and the United States just in the last year have raised Kim’s profile but have not gained him what he needs most, money.

Significant questions remain, nonetheless, about the exact impact of the trade actions on the economy and the livelihood of the people, especially as the UN Food and Agricultural Organization reports increased food shortages and hunger after a weak 2018 harvest and sharply reduced foreign aid, and as Kim shifts his public stance from prosperity to self-reliance. A close look at Chinese trade patterns in recent quarters, discussed below, helps but does not answer all the questions. The food shortages, in particular, would seem to have little or nothing to do with trade sanctions but a general slowdown or decline in the economy, caused by the regime’s likely extremely tight monetary policy, may be hurting overall employment and business conditions. Observed price drops for rice and corn may not, in these circumstances, be evidence of plentiful food conditions.The food situation in particular thus will bear close examination in months to come.

Continued Depressed North Korea-China Trade

Despite a slight rebound in March from historic February lows, China’s trade with North Korea remains at very depressed levels, this according to official Chinese customs data released last week. UN sanctions are keeping imports from North Korea at minimal levels, only $54.6 million in the first quarter, about flat over the past four quarters and down from a quarterly average of about $600 million prior to 2018.[i] Fewer sanctions have been levied on sales to North Korea but these, and a loss of North Korean buying power, reduced Chinese exports to only $455 million, about half their pre-2018 quarterly levels.

With two years of data since strong sanctions were imposed by Beijing, year-over-year commodity details can show interesting trends and give hints as to how North Korean industry is responding to what must be regarded an all-out “trade war” between the two countries. For instance, the largest two-way trade item is now timing devices, presumably since they are not sanctioned,with traders anxious to take advantage of North Korea’s skilled and available workforce and Chinese technology. China shipped $18.2 million of these timing mechanisms in the first quarter and imported $19.1 million in finished clocks and watches, suggesting significant new job creation for North Korean workers in only a year. With time, more such small-scale manufacturing for export may give a little life to what must be a hard hit North Korean industrial workforce. Footwear is another unsanctioned item that would appear to have large potential.Clearly, though, it will take years for this kind of trade to replace the lost billions in trade in minerals, metals, and textiles trade.

Other Chinese imports are essentially non-consequential, as coal, metals, minerals, most textiles, fish products, and machinery are all embargoed. Ferro-silicon, an alloy used in the steel industry increased somewhat to $7 million in the first quarter, as China apparently classifies it as a non-metal. Human hair wigs have jumped in value from almost nothing to about $7 million as well, interesting since this is one of the products that launched South Korea’s export drive in the early 1960s. North Korea thus quickly eclipsed the continuing South Korean wig sales to China in the first quarter. Molybdenum and tungsten ores, and electricity, produced in hydro plants along the Yalu River, also provided North Korea with $2-3 million each in the first quarter.

Chinese Imports from North Korea (million U.S. dollars)

| First Q 2017 | First Q 2018 | First Q 2019 | |

| All Commodities | 483.2 | 57.1 | 54.6 |

| Clocks & Watches | 0 | 4.2 | 18.1 |

| Wigs | 1.4 | 4.7 | 6.8 |

| Ferro Silicon | 4.7 | 5.2 | 7.5 |

| Foot ware | .6 | 1.2 | 1.6 |

| Fish Products | 22.9 | 0 | 0 |

| Textiles | 121.1 | .1 | 0 |

| Coal | 219.5 | 0 | 0 |

| Metal Ores | 63.4 | 5.9 | 3.7 |

The slight first quarter increase in aggregate Chinese exports to North Korea from year-earlier levels hides two important sub trends; a huge drop in capital goods exports—all kinds of machinery and electronic products, industrial parts, and vehicles, all prohibited by sanctions—and a fairly steady if not increasing flow of consumer products including foodstuffs, which are not embargoed.In addition to the jump in watch parts, Chinese sales of synthetic fibers, for instance, rebounded to $27 million, despite the freeze on Chinese imports of textiles suggesting either large scale sanction evasion or domestic, North Korean use of the Chinese products. With crude oil imports capped and refined product imports sharply reduced, North Korea has essentially no working petrochemical industry, and depends on poor quality coal-based materials. Other Chinese consumer goods continue to be exported, suggesting North Korean merchants are importing such products to sell in the markets with little hindrance from the authorities who presumably would prefer to save the foreign exchange. Imports of Chinese tobacco, for instance, have soared, as have beverages and milled grain products. One might expect private grain imports to increase sharply as well if food shortages become prevalent.

Chinese Exports to North Korea (million U.S. dollars)

| First Q 2017 | First Q 2018 | First Q 2019 | |

| All Commodities | 721.4 | 414.5 | 455.0 |

| Timing Devices | 1.2 | 4.8 | 19.8 |

| Synthetic Fibers | 46.4 | 18.2 | 31.0 |

| Apparel | 34.1 | 10.7 | 13.6 |

| Plastic Sheeting | 9.8 | 8.0 | 9.1 |

| Seafood | 32.6 | 17.3 | 17.5 |

| Grain | 1.0 | 0.4 | 1.8 |

| Milled | 1.4 | 26.9 | 16.4 |

| Soybeans | 19.9 | 29.5 | 22.1 |

| Tobacco | 3.1 | 17.2 | 17.7 |

| Fertilizer | 17.0 | 7.5 | 3.9 |

| Machinery | 140.2 | 14.5 | .1 |

| Vehicles | 52.8 | 1.9 | .1 |

Pyongyang’s Response to Sanctions

The absence of official balance of payments data makes it difficult to assess how the $400 million first quarter goods trade deficit with China is being financed. Trade with other countries is essentially negligible but North Korea likely runs a small services surplus from tourism and from transfer payments from the Korean diaspora and from the forced repatriation of wages of its overseas workers. These may fill about half the gap but UN restrictions on overseas labor are coming into force this year and by December, all North Korean workers are supposed to be sent home. For the remainder, most likely the country is gradually expending down foreign exchange reserves held by the Kim family, the government itself, and out of the apparently large amounts of foreign cash held by the population and in circulation.

Oddly, despite the trade pressures, the won currency continues to trade in North Korean markets at what appears to be an almost pegged rate to the U.S. dollar and Chinese yuan, this for now five years.

China-North Korea Trade Balance (million U.S. dollars)

| First Q 2017 | First Q 2018 | First Q 2019 | ||||

| China imports | 483.2 | 57.1 | 54.6 | |||

| China exports | 721.4 | 414.5 | 455.0 | |||

| China Surplus |

|

357.4 | 400.4 |

In the past, the North Korean regime, like many others facing this dilemma, would have either forcibly stopped foreign exchange trading and taken up all the foreign cash it could find, imposing tight currency controls, or it would let the won depreciate to the point foreign imports were unaffordable and exports highly advantaged. But in this case neither has happened, probably because of lessons learned in 2009 when an abrupt forced change back-fired and people began to resist the taking of their money. Instead, evidence increasingly points to a reverse policy, one that limits the issuance of won currency and won credit to keep its supply in line with a dwindling dollar supply, and thus the rate between the two currencies steady. The steadiness over five years sharply reduces speculation against the won. And perhaps most importantly, by allowing the public to hold a viable money, either U.S. dollars or Chinese yuan, for the first time in generations the regime is allowing the public to build financial savings, a process that dampens demand and inflation, but which gives them private resources for the future. But the policy is not costless. By restricting the won money supply, the regime harms its own budget and may have sent the economy into recession, with overall demand slumping, not just for foreign goods but for domestic goods and services as well. This is suggested by numerous stories from inside North Korea of factories closing for lack of demand, and of markets losing participants. Complaints are not that prices are too high, or that goods are not available, but that no one has enough money to spend. [ii]And, to the limited extent that we can observe, the overall price level seems to be dropping, not rising as one might expect given a foreign exchange shortfall. Rice and corn prices, for example, are at many year lows, despite what foreign observers say was a poor harvest.

At some point presumably Kim will relent and issue more paper currency, hoping the exchange rate will hold or that no one will notice. Foreign food aid or a reduction in sanctions might provide some, but temporary relief. A viable far reaching but non-socialist solution would be for him to issue more currency, perhaps by raising state salaries, and then to then pull it back in by selling off to private North Korean buyers some of the regime’s huge, but illiquid physical assets .Privatization on that scale occurred in China and in Russia decades ago. Private ownership of more of the country’s “means of production,” for instance the de-collectivization of agriculture, would enhance productivity and set the economy on a growth track, even with the sanctions intact, but much stronger if de-nuclearization occurs and sanctions are ended. In the meantime, budgetary pressures must be enormous and growing, while tough decisions await resolution.

William Brown is a non-resident scholar at KEIA and teaches at Georgetown University and UMUC. This and other related postings can be found on his website, NAEIA.com

Photo from Boaz-Guttman’s photostream on flickr Creative Commons.

[i] All trade data is from Global Trade Atlas and other trade data amalgamators which directly obtain official Chinese Customs Bureau data.