The Peninsula

Number of North Korean Defectors Going to South Korea Remains Low, but They Are Receiving Increased Attention

The number of defectors fleeing North Korea and resettling in South Korea remains at very low levels. The number had begun to decline before 2020, but the COVID-19 pandemic led Pyongyang to enforce harsher border controls to prevent North Koreans (and others) from entering the country from abroad and potentially bringing the virus with them. This heightened border enforcement made it much more difficult for North Koreans to leave the country without government authorization, and few were given approval to go abroad. Yet while defections have decreased, defectors themselves have been elevated within South Korea by a South Korean administration intent on emphasizing human rights and a new vision for a unified Korean Peninsula.

With the election of President Yoon Suk-yeol in March 2022, South Korea was expected to move closer to and strengthen military links with the United States, which has clearly taken place. In addition, the Yoon administration has been more active and assertive on the issue of human rights in North Korea, highlighted when South Korea’s Ambassador to the United Nations, as President of the UN Security Council, presided over a recent discussion of North Korean human rights as a threat to international peace and security. And, domestically, the Yoon government established a national holiday, “Defectors’ Day,” to commemorate North Koreans who have settled in the south, celebrate forms of cultural expression from both Koreas, and provide space for diasporic activism not permitted in North Korea.

Data Shows Dramatic Drop in Defections

It was never easy for North Koreans to leave without official sanction, but the borders were far more porous before the pandemic forced tighter border control. By 2019, over a thousand North Koreans were successfully leaving the North annually and making their way through China to receive refuge in South Korea. There were a few who sought resettlement elsewhere, but those numbers were much smaller. During 2020, the number dropped dramatically. In 2019, South Korea reported that 1,047 defectors/refugees were resettled in South Korea. The following year, the number dropped to 229, and in 2021, the number was only 63. During the first six months of 2024, the number of defectors reaching South Korea was 105 – a very modest increase from the levels reported since the beginning of the pandemic in early 2020.

Official South Korean statistics report the number of defectors admitted into South Korea over the past 12 years:

|

Number of North Korean Defectors Admitted to South Korea |

|

| Year | Number of Defectors |

| 2012 | 1,502 |

| 2013 | 1,514 |

| 2014 | 1,397 |

| 2015 | 1,275 |

| 2016 | 1,418 |

| 2017 | 1,127 |

| 2018 | 1,137 |

| 2019 | 1,047 |

| 2020 | 229 |

| 2021 | 63 |

| 2022 | 67 |

| 2023 | 196 (Full year) |

| 2024 | 105 (First six months of the year) |

The annual number of defectors remained relatively constant from the time Kim Jong-un assumed leadership in January 2012 until the pandemic began in early 2020. During the first eight years of Kim’s rule, the annual number ranged from 1,000 to 1,500. By comparison, during the last years of his father Kim Jong-il’s rule, official statistics show over 2,000 North Koreans were entering the South annually, with a peak of 2,914 in 2009.

It is noteworthy that the percentage of defectors entering South Korea includes a disproportionate number of women. Only during two years of the pandemic did defectors include a higher number of men than women – 23 women of 63 total defectors in 2021 (37 percent) and 35 women of 67 total defectors in 2022 (48 percent). Other than those two years, the percentage of female defectors fluctuated but showed significantly more women than men leaving – 85 percent were women in 2018 and 69 percent in 2020. Of the 105 North Korean defectors who entered South Korea in the first half of 2024, only 10 were men and 95 were women.

The Risks and Dangers of Crossing Through China

Few defectors are able to go overland or by boat from North Korea directly to South Korea. There are only very rare exceptions to this pattern. The border is strictly guarded, as are North Korea’s coastal waters. Border troops are under orders to shoot-to-kill if anyone gets too close to the border. Furthermore, the North Korean side of the border area is covered with land mines and other military devices to kill would-be escapees. Because North Korean military forces are so concentrated at the border, and because internal travel in the North is carefully regulated, it is difficult for North Korean residents to even get near the boundary along the 38th parallel unless they are among the military personnel guarding the border or the few civilians permitted to live in those areas.

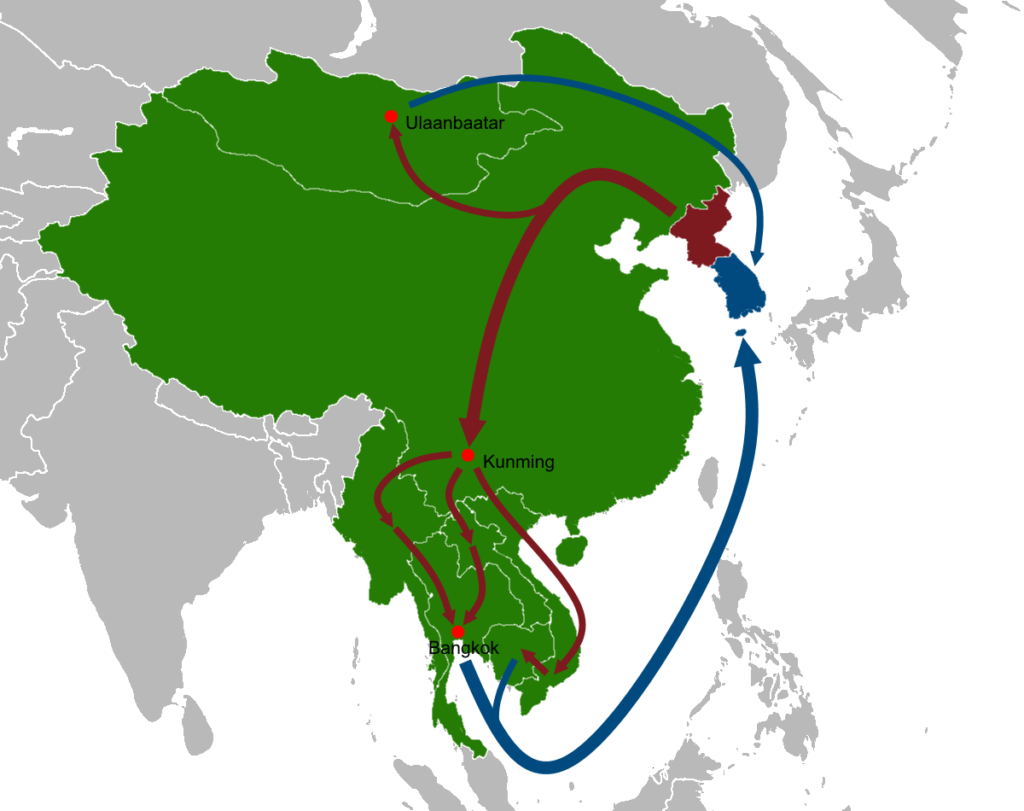

The overwhelming number of defectors escape the North by crossing overland and going through China, a journey marked by severe risks and dangers. Those who successfully escape have the help of smugglers, many of them South Korean citizens who are paid for their knowledge of how to cross the border and travel through China. The defectors then generally cross out of China into Laos, Thailand, or Myanmar, again with the help of smugglers.

Vietnam is not a safe escape route because the country has a particularly close relationship with China. The Vietnamese border with China is guarded more strictly, and few, if any, defectors have successfully crossed into Vietnam and reached South Korea. The Vietnamese government has previously returned North Korean defectors to Chinese officials, who promptly returned them to North Korea. This was done despite the request of the South Korean government and pleas of international human rights organizations that the individuals be permitted to go to South Korea.

Because of the difficulty of internal travel in North Korea, defectors who have successfully left North Korea and resettled in the South are principally from two provinces that have lengthy borders with China – the provinces of North Hamyong and Ryangang. These two provinces comprise about 12 percent of the total North Korean population, but residents of these two provinces make up 76 percent of defectors who have resettled in South Korea over the last two-and-a-half decades. (See South Korean government data on North Korean defectors.)

At the beginning of the pandemic, a significant number of North Koreans were living and working in Northeast China, where they found better economic opportunities. Some were there with the North Korean government’s permission, and some were there without the knowledge or consent of Pyongyang. None of these individuals were permitted to return to North Korea after the pandemic struck, even though they were North Korean citizens. With the waning of the pandemic, the Chinese government sought to remove these “illegal immigrants,” and Pyongyang was under pressure to permit the return of the North Koreans to their homeland.

In October 2023, human rights groups and the South Korean government reported that as many as 600 North Koreans were being forcibly returned to the North, and the South Korean government has raised the issue with the Chinese government. UN Special Rapporteur on Human Rights in North Korea Elizabeth Salmon estimated that the number of North Koreans being held in China at that time was as high as 2,000 and called the forced repatriation a violation of international law and procedure. In December 2023, a Seoul-based human rights group reported that some 600 North Koreans had been deported from China to North Korea against their will and that all “vanished” when they reached North Korea.

Defectors’ Day: South Korea Honors Refugees with a New Public Holiday

Earlier this year, the South Korean government under President Yoon Suk-yeol established “Defectors’ Day” as a new national holiday to be celebrated annually on July 14. The holiday was established to recognize the legal, social, and other benefits for North Koreans who have made the decision to leave the North and become citizens of South Korea.

July 14 was the date on which the South Korean government enacted the North Korean Defectors Protection and Settlement Support Act in 1997. The legislation established government policies to aid the defector community. It provides help for new arrivals from the North and assures that they are given necessary assistance in the South. While some have argued that a special Defectors’ Day only serves to emphasize the differences between defectors and the South Korean population, others argue that it is a way of welcoming and acknowledging the new arrivals from the North.

The celebration of the first Defectors’ Day took place in Seoul and included performances of North Korean music and displays of North Korean objects brought by the defectors when they left their homes in the North. Some defectors also sold North Korean liquors, clothing, and food.

It is ironic that the holiday was created at a time when new arrivals from North Korea have dropped to their lowest level in 25 years. At the same time, however, it highlights the Yoon administration’s commitment to the human rights of North Korean defectors as an integral part of the government’s policy toward North Korea. President Yoon’s administration has highlighted South Korea’s concern and commitment toward North Korean refugees, reflecting his vision of unity between the people of North and South Korea. Kim Jong-un, on the other hand, is emphatically moving away from the idea of Korean unity and the belief in a shared history and heritage of the Korean people. The South Korean government’s increased attention toward defectors is a part of that broader policy on inter-Korean issues.

Robert R. King is a Non-Resident Distinguished Fellow at the Korea Economic Institute of America (KEI). He is former U.S. Special Envoy for North Korea Human Rights (2009-2017). The views expressed here are the author’s alone.

Photo from Ceosad on Wikimedia Commons.

KEI is registered under the FARA as an agent of the Korea Institute for International Economic Policy, a public corporation established by the government of the Republic of Korea. Additional information is available at the Department of Justice, Washington, D.C.