The Peninsula

North Korea’s Strategic Play in an Era of Great Power Confrontation

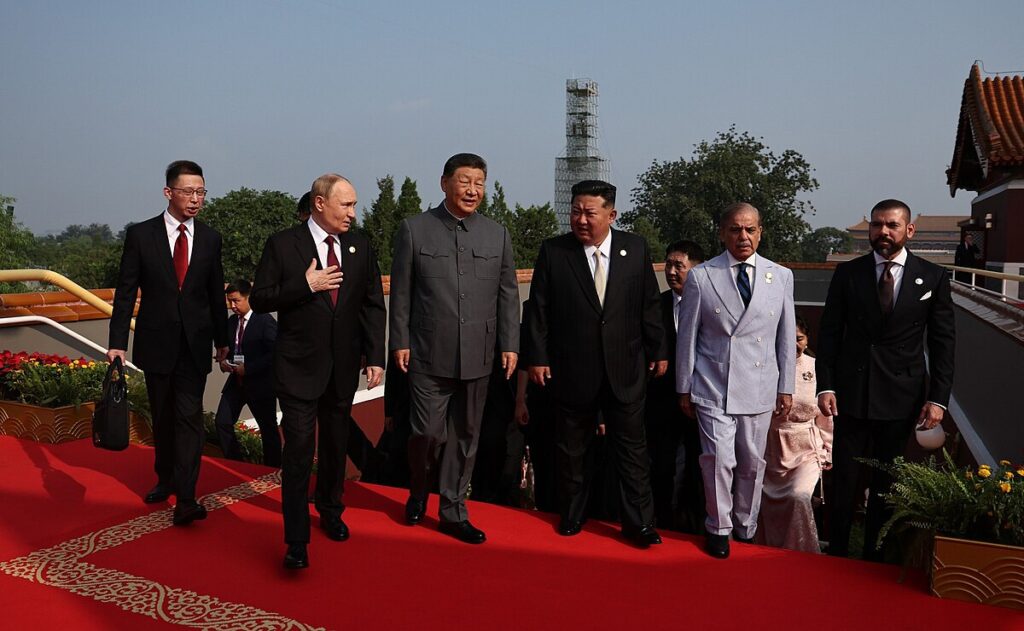

North Korean leader Kim Jong-un’s attendance at China’s Victory Day parade in September reflects a potentially ominous development in Northeast Asia’s regional security landscape. At Tiananmen Square, Kim stood alongside Chinese and Russian leaders—just as his grandfather did in 1959—a display widely interpreted as a gesture of opposition to the United States and the Western-led order. For many Koreans, this image evokes a return of the new Cold War on the Korean peninsula.

The appearance of Chinese Premier Li Qiang and the ruling United Russia Party Chairman Dmitry Medvedev at Kim’s October military parade in Pyongyang to mark the 80th anniversary of the founding of the Workers’ Party of Korea suggest strengthening trilateral alignment and partnership among North Korea, Russia, and China.

After decades of diplomatic isolation, economic destitution and marginalisation in the post-Cold War era, North Korea is returning as a destabilising force. Armed with nuclear weapons and an enabler of Russia’s war of attrition in Ukraine, North Korea may be a force for the reshaping of great power dynamics in Northeast Asia.

North Korea’s return to global politics as a significant player—alongside the far more powerful Russia and China in trilateral diplomacy against the United States—reflects a dramatic shift in Kim’s foreign policy tactics compared to his first decade in power.

During Kim Jong-un’s first decade in power, North Korea’s foreign policy was marked by confrontation, isolation and nuclear development, as well as experimentation with economic reform. He focused on consolidating domestic power, while adopting his grandfather Kim Il-sung’s policy of Pyongjin (the simultaneous development of the economy and nuclear weapons) and pursuing hostile policies towards South Korea and the United States.

North Korea’s relentless provocations and nuclear development alienated its key patrons, especially China. For Beijing, Kim’s missile launches and nuclear tests jeopardised China’s core interests on the Korean Peninsula, regional stability and the global non-proliferation regime. Kim’s defiance despite Beijing’s repeated warnings frustrated the Chinese government and increased North Korea’s isolation and mistrust towards China.

In comparison, North Korea’s relations with Russia were relatively amicable in the first decade of Kim Jong-un’s leadership, albeit limited. In 2012, Russian President Vladimir Putin demonstrated goodwill towards the fledgling Kim regime by writing off 90 per cent of North Korea’s Soviet-era debt. Moscow also sought enhanced cooperation with North and South Korea both, specifically through the construction of the Trans-Korean rail and pipeline projects and the development of the Russian Far East.

In 2014 and 2015, there was a brief rapprochement between Russia and North Korea as North Korea–China relations deteriorated further. Pyongyang and Moscow had high-level official government engagements and reached investment agreements to modernise North Korea’s transportation infrastructure in exchange for Russian access to its natural resources. But this rapprochement was short-lived and achieved little after North Korea’s nuclear and missile tests and subsequent UN sanctions in 2016.

Mutual mistrust deepened in 2016 and 2017 when both Beijing and Moscow supported five UN Security Council resolutions which restricted North Korean seafood, textile and energy exports in response to its intercontinental ballistic missile and nuclear tests. Neither Chinese President Xi Jinping nor Russian President Vladimir Putin met Kim Jong-un until 2018 and 2019, respectively, after Trump’s diplomatic move towards Pyongyang.

What caused the shift in North Korea’s foreign relations with China and Russia? The outbreak of the Russia–Ukraine war in 2022 was a major inflection point.

Before Russia invaded Ukraine on 24 February 2022, Pyongyang was grappling with internal and external setbacks. After the failed Singapore and Hanoi summits with US President Trump in 2018–2019, Kim turned inward and launched a five-year weapons development plan. Relations with China cooled as North Korea resumed military provocations and revealed its unrestrained nuclear ambitions. When the COVID-19 pandemic hit, Pyongyang imposed an unprecedented national lockdown in January 2020 that lasted more than three years. The self-imposed quarantine proved more effective in inducing North Korean isolation than UN-mandated international sanctions, with North Korea’s trade with China dropping by more than 80 per cent in 2020.

After severe economic hardship from its self-imposed border closure, the Russia–Ukraine war provided an opportunity for Kim to draw Russia closer. He began by vetoing the UN resolution that condemned Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in March 2022 and North Korea recognised Russia’s occupation of Donetsk and Luhansk in July 2022. Moscow welcomed Pyongyang’s support. In August 2022, Putin called for their countries ‘to expand the comprehensive and constructive bilateral relations with common efforts’. In November, Pyongyang reportedly supplied the Russian mercenary Wagner Group with missiles and infantry rockets, initially in exchange for grain and horses.

Bilateral military cooperation deepened as Russia faced ammunition shortages in prosecuting the war. Russian Defence Minister Sergei Shoigu met with Kim in July 2023, reportedly to discuss arms deals, paving the way for a summit between Kim and Putin that September. According to the Open Sources Center, North Korea delivered approximately 4.2–5.8 million artillery shells to Russia between September 2023 and March 2025. In October 2024, North Korea deployed around 10,000 troops to assist Russia in Ukraine—the first significant North Korean overseas deployment since the end of the Korean War.

The outcomes of Kim’s gambit with Russia were astounding. During Putin’s visit to North Korea in June 2023, the first for a Russian president in 24 years, North Korea revived the mutual defence treaty alliance it once had with the Soviet Union. Expanded defence cooperation led to strategic alignment between Pyongyang and Moscow in their ‘fight against the imperialist hegemonistic policies of the United States and its satellites’.

Economic ties also deepened, with Russia becoming a supplier of food, energy and hard cash for North Korean workers. In March 2024, Russia further undermined the UN’s ability to enforce international sanctions on North Korea by vetoing the UN resolution to renew the panel of experts monitoring sanctions, providing North Korea with superpower protection and a shield against UN measures.

Unlike in 2016 and 2017, when Kim was desperate for a summit with US President Donald Trump to lift sanctions, in 2025 there is little urgency to seek dialogue with the United States. Instead, summitry with Putin provides a substitute symbol of international legitimation of North Korea’s nuclear status.

North Korea’s strategic partnership with Russia, combined with Trump’s return to the White House in January 2025 and diplomatic entreaties with Kim, led to a diplomatic opening in China–North Korea relations in September 2025. To improve its strained ties with North Korea over the latter’s increasing partnership with Russia, Chinese President Xi invited Kim to China’s Victory Day parade and accorded him special treatment by placing him second in the protocol order, immediately after Putin. Xi and Kim held their first summit since 2019. Although the respective official readouts downplayed points of difference such as denuclearisation, North Korean Foreign Minister Choe Son-hui’s visit to China in late September 2025 suggests that active shuttle diplomacy may resume between Beijing and Pyongyang.

An important question going forward is whether Kim will reprise North Korea’s tactic of playing Russia and China against each other, or unite them as a counterweight to US–Japan–South Korea trilateralism. At this point, Kim appears to want stronger relations with both Russia and China. His cautious approach to restoring ties with China may be a hedge against uncertainty regarding the durability of North Korea’s strategic partnership with Russia and in anticipation of renewed engagement with President Trump.

Any form of trilateral partnership continues to be constrained by mutual mistrust and a divergence of interests with China hesitant to cast its lot with its sanctioned North Korean and Russian counterparts. China is unlikely to allow full-blown confrontation with the United States and is acutely aware of the benefits of being economically intertwined internationally, despite US-led derisking initiatives. China’s political trump card is the economic dependency it has within the Asia Pacific region, which may be strengthened by Trump’s trade policies. China will not want to throw away that leverage without getting something in return.

China has consistently opposed the acceptance of North Korea as a nuclear power, in contrast to Russian analysts who treat it as an unfortunate reality and consequence of past mistakes in dealing with North Korea. But the lack of outright condemnation and calls for denuclearisation suggest Beijing may now view denuclearising North Korea as an unattainable goal.

Russia’s war in Ukraine and intensifying US–China competition have undermined US strategy towards North Korea, leaving Washington with few practical policy options to pressure North Korea into denuclearisation. Having accelerated its nuclear build-up in the past five years, North Korea has also further solidified its position as a de facto nuclear power. Against this backdrop, Donald Trump’s return to the presidency and the election of a progressive leader in South Korea have revived the prospects for Kim–Trump summit diplomacy 2.0.

In January 2025, Trump described North Korea as a ‘nuclear power’ and has continued to extend an olive branch for dialogue. South Korean President Lee Jae Myung vowed to act as a ‘pacemaker’ to help Trump become a ‘peacemaker’ on the Korean Peninsula. Recognising that denuclearisation is an unrealistic short-term goal, the Lee government has proposed a three-step denuclearisation plan aimed at fostering US–North Korea dialogue without getting stalled on the denuclearisation goal.

Kim Jong-un is now sending signals of openness to meet President Trump. In late September, he publicly expressed his openness to another meeting with the United States on the condition that the United States drops its denuclearisation demand. This contrasts sharply with Pyongyang’s radio silence to the former Biden administration’s diplomatic outreach and suggests that Kim believes he has a new (and real) chance to extract additional concessions from Trump.

The second Trump administration’s responses to North Korea are bifurcated due to a disconnect between Trump’s desire for engagement and the default bureaucratic responses dictated by US–China competition, US interests and the global non-proliferation regime. Trump’s eagerness to engage could also unsettle the China–North Korea–Russia relationship, since any interaction between Trump and Putin, Xi or Kim risks stoking distrust.

Some of Trump’s advisers may therefore support reengagement with Kim as a way to stress test the alignment. Sceptics will question the utility of a Trump–Kim summit, fearing the consequences for US denuclearisation goals and extended deterrence to allies. Bureaucratic caution will make it unlikely that the United States will fully abandon the goal of denuclearisation or allow North Korea to be recognised as a legitimate participant in Western economic and political systems.

But the much anticipated resumption of a Trump–Kim summit did not happen—despite Trump’s active outreach—during his visit to South Korea in late October 2025. Though Trump did not mention denuclearisation, Kim’s rebuff of Trump’s engagement effort shows that the North Korean leader may have desired a clear and direct signal from the US President that denuclearisation was off the table before accepting a meeting.

Moreover, prospects for a Trump–Kim meeting have declined now that the Trump and Lee governments have formally reaffirmed in a joint fact sheet their shared commitment to the denuclearisation of North Korea. Trump has also given ‘approval’ for South Korea to build nuclear-powered submarines. North Korea’s visceral negative response to that statement appears to preclude the resumption of the US–North Korea dialogue, at least in the near-term.

Kim’s strategic play on the Korean Peninsula has already reshaped the security landscape. With Russia and China increasingly mute on denuclearisation and South Korea poised to prioritise a nuclear freeze as a policy priority, a nuclear arms control deal could emerge as an alternative objective. Whether Trump would be interested in an arms control deal with North Korea remains uncertain. But Kim would likely view this as a step towards achieving nuclear state status, which makes his future diplomatic manoeuvring all the more concerning.

Scott Snyder is President and Chief Executive Officer at the Korea Economic Institute of America. The views expressed are the author’s alone.

Ellen Kim is Director of Academic Affairs at the Korea Economic Institute of America. The views expressed are the author’s alone.

This article appears in the most recent edition of East Asia Forum Quarterly, ‘Managing industrial subsidies, Vol 17, No 4. The full edition is available at ANU Press.

Photo from the Kremlin via Wikimedia Commons .

KEI is registered under the FARA as an agent of the Korea Institute for International Economic Policy, a public corporation established by the government of the Republic of Korea. Additional information is available at the Department of Justice, Washington, D.C.