The Peninsula

North Korea’s Pegged Won Wiggles, But Doesn’t Break, Yet

By William B. Brown

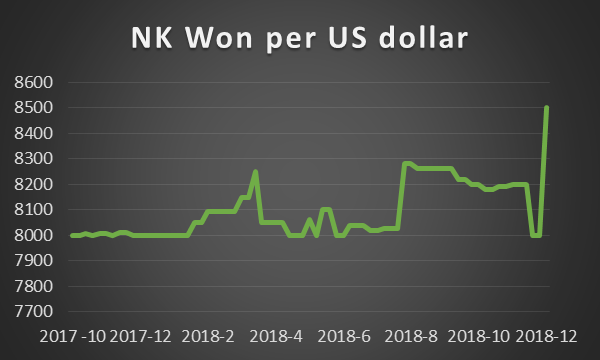

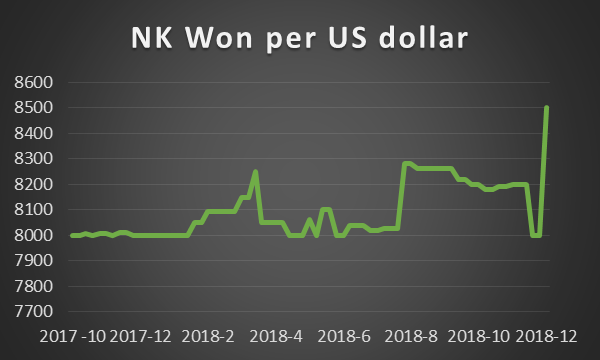

North Korea’s won has slipped ever so slightly against the dollar in recent weeks. This is not surprising given the dollar’s worldwide strength but presents an interesting conundrum for the Chosun central bank. It no doubt knows that pegged currencies could break suddenly when a small divergence, a wiggle, catches the public’s attention. Any signs of the country running out of reserves could lead to people dumping the local money in a panic to exchange for safer assets. A self-sustaining downward spiral can occur, eviscerating the currency and causing all kinds of social instability.

North Korea Daily reports the dollar traded at 8,500 won in Pyongyang on 26 December, up from a steady 8,000 won through the middle of the year, a devaluation of 6 percent.

Against the globally weaker yuan, won has been more volatile, but without the trend decline.

An incipient currency crisis began in North Korea in 2009 and stopped only with the execution of the party finance chief and a very rare Worker’s Party apology. Since then, financial authorities under Kim Jong-un have done an extraordinary job keeping the won stable. Despite the extremely tough sanctions against the economy, free circulation of competing assets – the U.S. dollar and the Chinese yuan – helped moderate the won’s volatility.

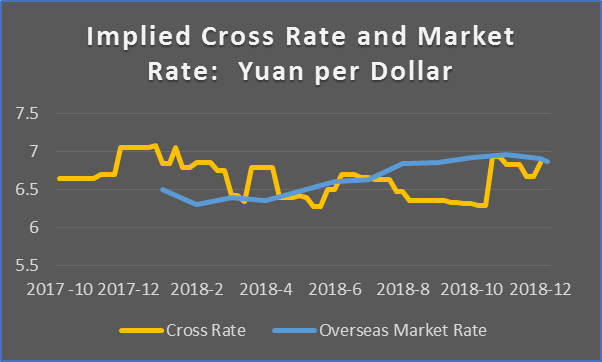

The gap between U.S. dollar/yuan exchange rate as measured by their value in the North Korean market (cross rate) and the actual exchange rate value in overseas markets did grow in 2018, indicating the potential for corrosive arbitrage behavior.

But the cross rate implied by the won for dollars and yuan is now exactly consistent with the overseas dollar/yuan rate. This suggests a remarkably free-flowing foreign exchange market in North Korea despite its socialist underpinnings.

Parsimonious printing of notes and limited credit expansion probably contributed to the won’s steadiness as well, although a tight monetary policy adds its own stresses to the state’s economy.

So, the question on every North Korean’s mind, and especially on Kim’s as he travels to Beijing, must be, how long this can last.

One is hesitant to guess what caused the recent dollar uptick, either market forces surrounding the strong dollar overseas or the continuing drain on the country’s foreign exchange exhibited by the huge drop in its exports due to sanctions. Chinese merchandise trade data suggest a $200 million monthly outflow for most of 2018, unlikely offset by significant services or remittances inflows.

Recent commodity-by-country trade data released by China (with a six-month delay) reveal the conspicuous absence of exports of electrical and non-electrical machinery, and vehicles to North Korea. This may suggest that the country is running out of foreign exchange and can’t afford any investment related purchases.

Alternatively, the authorities may be trying to inoculate the market so that participants do not expect a firm peg. This ensures that future movements are not seen as policy failures or an impending crisis. If this is the case, we should see the dollar fall back to the 8,000 won level quickly as the central bank intervenes and spends dollars for won repurchases.

Another guess, expressed recently by some scholars, is that the won is actually more closely tied to yuan; therefore, the yuan’s decline against the dollar automatically made for the won decline. As the above graphs show, however, the won’s value against the yuan has tended to be much more volatile than against the dollar. Alternatively, some kind of basket approach may be in use but that removes the confidence-building features of a simple dollar peg, and confidence is what North Korean markets need more than anything.

What we do know is that anyone holding dollar assets in North Korea over the past few weeks has become relatively better off than those holding dollar liabilities such as apartment mortgages. One might think this could be cause for regime concern. We don’t know but is it enough for a quick trip to Beijing and a friendly chat with President Trump?

William Brown is an Adjunct Professor at the Georgetown University School of Foreign Service and a Non-Resident Fellow at the Korea Economic Institute of America. He is retired from the federal government. The views expressed here are the author’s alone.

The author is indebted to Daily North Korea which diligently reports North Korean prices and exchange rates in its newsletter. https://www.dailynk.com/

Picture from user Price Roy on flickr