The Peninsula

North Korean Sanctions Evasion: The UN Panel of Experts Report

Despite the completion of the internal policy review and a successful summit, newly-appointed North Korea envoy Sung Kim faces many of the same constraints that have long plagued U.S. North Korea policy. The Biden administration has rightly acknowledged that any engagement implies “a calibrated, practical approach.” But there are simply not that many policy levers that can be moved around and the questions are sadly familiar. How will the maintenance and enforcement of UN Security Council sanctions play into any offers the United States and its allies might be willing to make? How does pressure combine with engagement? And above all, what is the current sanctions evasion landscape? The recent UN Panel of Experts report on the issue provides sobering new information on the extent of the leakage, and it has clearly reached wholesale proportions.

In a December webinar, former Deputy Special Representative for North Korea Alex Wong outlined some surprising information on US intelligence on the issue. In 2020 alone, U.S. vessels observed 32 individual occurrences of fuel smuggling ships in Chinese coastal waters, 555 separate occurrences of ships carrying UN prohibited goods from North Korea to China—predominantly coal—and 155 occasions where Chinese-flagged coal barges sailed into North Korea and returned to Chinese ports with illicit cargo. Despite the United States alerting Chinese Navy and Coast Guard on 46 separate occasions that vessels engaged in smuggling had fled into Chinese coastal waters, Chinese authorities do not appear to have done much to stem the tide.

The UN Panel of Experts report provides significant detail. The Panel was established in 2009 to conduct “credible, fact-based, independent assessments analysis, and recommendations” on the implementation of Security Council resolutions. The Panel consists of eight experts with backgrounds in WMD and arms control, nuclear non-proliferation, customs and export controls, maritime transport and finance, and has steadily strengthened its forensic capabilities. It also reports information submitted by member states. Yet because the report is dense, press coverage does not always highlight the most significant findings.

Since Resolution 1718 in 2006, the UN Security Council has passed no fewer than nine resolutions gradually expanding sanctions on North Korea, with those passed in 2016-17 the most significant; they were the first to go after North Korea’s commercial trade. At this juncture, two sanctions measures are probably the most consequential: the cap on refined petroleum products in excess of 500,000 barrels per year; and the export ban on key commodities including coal, iron ore, seafood and textiles. The first matters because it goes to the heart of North Korea’s energy sector; the second because it limits foreign exchange earnings.

With respect to the first, the report notes that China notified the Committee of deliveries of just over 5,000 tons of refined petroleum to the DPRK in 2020, while the Russian Federation reported 12,800 tons. When converted, this amounts to approximately 207,000 barrels of petroleum products, well within the 500,000-barrel cap.

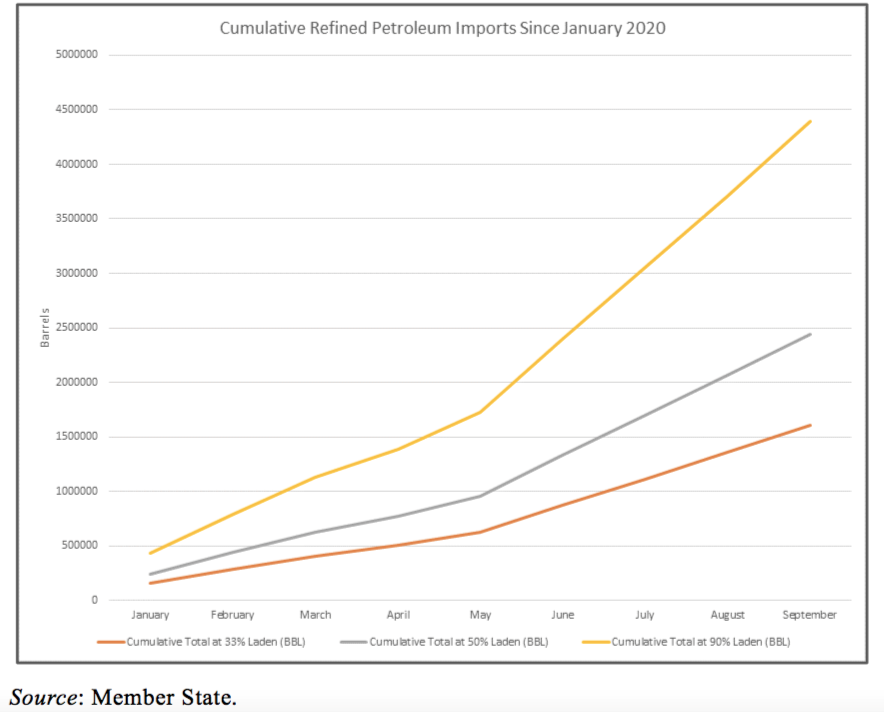

Yet according to a “Member State”—no doubt a euphemism for the United States—at least 121 additional shipments of refined petroleum products were delivered to the DPRK during the first nine months of 2020, none of which were reported to the Committee as required under paragraph 5 of resolution 2397 (2017). A simple graph is included in the summary of the report, based on a table providing data on these shipments included as an annex in the report; the graph is reproduced below. The report reproduces estimates on the size of the ships involved, and what they were carrying under different assumptions about lading. These additional unreported deliveries sum to 146,000 tons (approximately 1,700,000 barrels) if the ships were 33% laden, 221,000 tons (approximately 2,600,000 barrels) at 50%, and almost 400,000 tons (approximately 4,600,000 barrels) at 90% laden. This amounts to more than eight times the cap if the vessels were 90% laden, nearly five times if 50% laden, and over three times if only 33% laden on delivery.

Figure 1

Cumulative Undeclared refined petroleum imports since January 2020

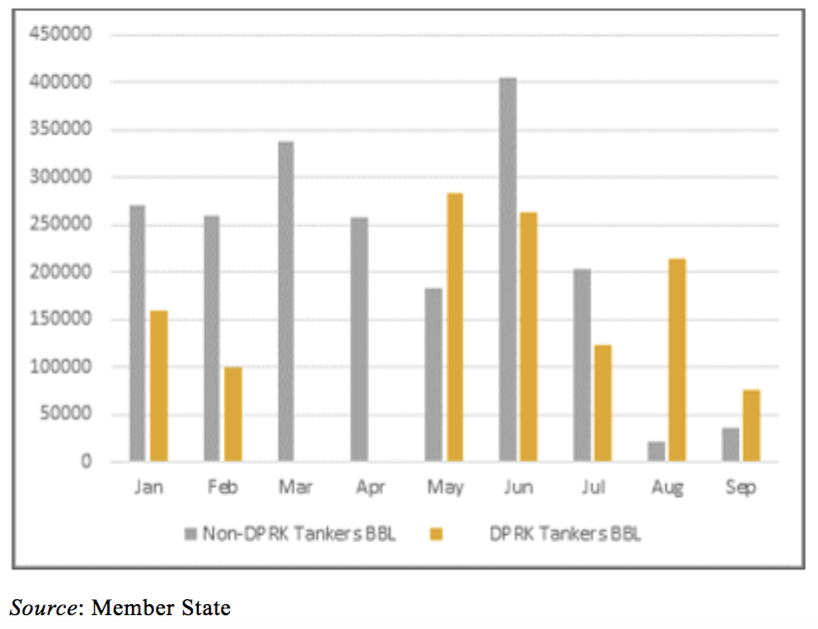

In addition to this data, the report estimates the share of these vessels that are North Korean flagged. (Figure 2). In the first half of the year, foreign flagged vessels accounted for the bulk of this traffic, but in the second half of the year North Korean flagged vessels caught up. In a footnote (21), the report clarifies that these deliveries were being procured “mainly” through the infamous ship-to-ship transfers on which there is now ample aerial and satellite imagery. North Korean ships are heading into international or Chinese waters, picking up fuel, and bringing it home. And these estimates are based on those that were detected; we need to assume that the error in that regard is almost certainly on the low side.

Figure 2

Calculated monthly refined petroleum imports by vessel type

To be fair, there is some ambiguity the UN report fails to address with regards to this data. First, in order to approximate the volume of refined petroleum shipments, the Panel assumes that all refined shipment products are liquefied petroleum gas (LPG) which uses the highest conversion rate of 11.6 from tons-to-barrels. By using this assumption, the magnitude by which the caps are exceeded may be overestimated. But even assuming all shipments are of products with the lowest conversion rate of 6.35—equally unlikely–the shipments are still well over the cap.

Second, the Panel assumes all of the reported shipments are distillates of refined petroleum and therefore does not consider the possibility that some of it could be crude oil, which is also capped. A recent report by David von Hippel and Peter Hayes suggests that Chinese crude oil exports to North Korea by sea have fallen, but the pipeline from Dandong to Sinuiju is still in operation. China’s customs statistics stopped including crude oil flows after 2013, but crude oil clearly continues to flow across the border, going straight into the Sinuiju refinery. Von Hippel and Hayes estimate that crude oil exports by pipeline from China to the DPRK in 2019 totaled 715,000 tons (approximately 5,233,800 barrels) and in an effort to help North Korea through the pandemic increased those exports to nearly 750,000 tons (approximately 5,490,000 barrels) in 2020. These are guestimates to be sure, but given that crude from all sources is supposed to be capped at 4 million barrels, there is the possibility of significant sanctions evasion on that front as well.

This month, the UN sanctions committee received Chinese export data on refined petroleum shipments to the DPRK for the first time since September. According to China, it shipped 587.4 tons (approximately 4,900 barrels) of oil to North Korea last month, less than one percent of the cap. Yet the UN Panel of Experts report suggests that these numbers are risible.

What are the implications for Sung Kim? If the United States can secure meaningful concessions from North Korea, then some sanctions relief might be warranted. But if the data reported by the UN Panel is correct, North Korea is already getting significant de facto sanctions relief. More troubling, however, is what the data suggests about likely cooperation from China on the issue. There is little doubt that Beijing could make a significant dent in sanctions evasion if it chose to prioritize the issue. But the evidence suggests sanctions regret: that the commitments China made at the UN were somewhat more substantial than they were willing to maintain. If pressure is a component of the calibrated approach, it is clearly not as significant as UN Security Council resolutions would have us believe.

Samantha Beu is a master student at the School of Global Policy and Strategy, University of California, San Diego. She received her Bachelor of Arts degree from The Ohio State University.

Stephan Haggard is a Non-Resident Fellow at the Korea Economic Institute and the Lawrence and Sallye Krause Professor of Korea-Pacific Studies, Director of the Korea-Pacific Program and distinguished professor of political science at the School of Global Policy and Strategy University of California San Diego.

Photo from U.S. Pacific Fleet’s photostream on flickr Creative Commons.