The Peninsula

North Korea and Global Food Prices: A Coming Shock?

Given the paucity of data on North Korea, the food prices provided by Rimjingang and DailyNK are often used for a variety of analytic purposes: to monitor seasonal fluctuations that most affect the poor; as a wider proxy for inflation; and as an indicator of larger constraints on the economy, including sanctions and the border closure. Benjamin Katzeff Silberstein has a nice summary in this vein at 38 North. Looking ahead, however, we will be watching these price trends for an altogether different reason: to find out whether the food price shock unleashed by the war in Ukraine will find its way into the North Korean economy.

There are good reasons to think that it will. North Korea is a closed economy in the sense that the share of trade to GDP is almost certainly lower than for other small countries. But North Korea is not a closed economy with respect to prices. As Marc Noland and I showed in Hard Target: Sanctions, Inducements and the Case of North Korea, North Korea’s economic fate has been closely tied to global price trends. Just as the North Korean economy saw gains in the run-up of global commodity prices such as iron and coal in the decade prior to the Global Financial Crisis, so it simultaneously felt the adverse effects of the food price spikes in 2007-8 and again in 2010-11.

To be sure, this link has been severed in recent years by the combination of sanctions and the closure of the border. Moreover, one hypothesis for the relative stability of grain prices through 2020 is that the government had stockpiled purchases from China in response to sanctions. While North Korea’s weather is never fully cooperative, the initial COVID shock was dampened by at least adequate harvests; Choi Ji-young has a thorough review in the KDI’s DPRK Economic Outlet last year.

These circumstances could well change. Because of the geopolitical implications for Europe, headlines on commodity prices have naturally focused on oil and gas markets. But the data on global food production is equally if not more sobering. Between them Russia and Ukraine account for 14% of wheat production and nearly 30% of exports and 19% of barley production and over 30% of exports. Ukraine alone accounts for 15% of world corn exports, and is the dominant supplier to China. The problem did not initially appear on the production side in the short-run; winter wheat was already planted prior to the war. Rather the closure and occupation of Black Sea ports are currently the most significant obstacles interrupting supply. But if the war persists, spring planting—when most of these food crops are sown—will be affected.

Trading Economics has excellent time series on commodity prices going back 25 years, which permit a long-run comparison with where we stand today. The picture is grim. Wheat prices have spiked at about the level of the February 2008 peak. Corn futures are trading at levels seen in prior food price shocks in 2008, 2011-12 and late spring 2021. Rice is more thinly traded, and came into the crisis with increased stocks in India and Thailand providing a cushion; prices have yet hit to hit the crest seen in the 2008 crisis. Nonetheless, the effects of rising prices of wheat will inevitably spill over to rice markets, which are also approaching highs touched briefly in 2011 and 2020.

So far, the effects of the food price spikes have been felt first in the regions most dependent on supply from the Black Sea, most notably the Middle East. Egypt is the canary in the coal mine. The effects of the war on food prices in the country were extraordinarily rapid and last week, the country turned—once again—to the IMF.

But there is no reason to think that North Korea will be immune. Moreover, the country comes into the crisis with well-known vulnerabilities including finances strained by sanctions, the adverse effects of the border closure on export earnings—even with large-scale evasion—and yet another cycle of adverse weather. Precipitation on the peninsula is at near record lows—in both South and North—with adverse effects on winter wheat and barley crops. However, as always the wider failures of the regime are once again on ample display. While reminding the world of its success at building longer-range missiles last week, top-down orders from the leadership to expand winter crops have hit constraints not only of weather but of long-standing underinvestment in irrigation systems, inputs and farming equipment. A significant, but as yet unknown, share of the winter crop will almost certainly be lost.

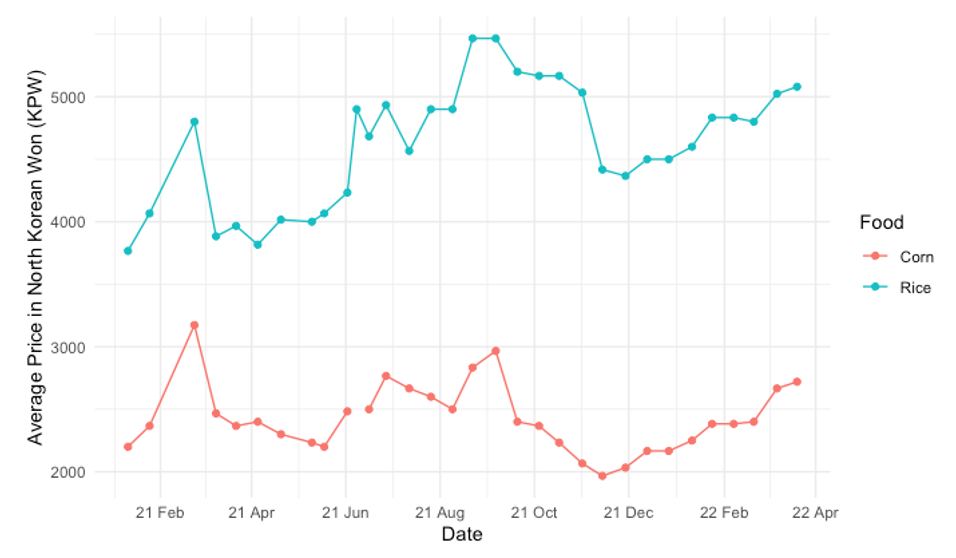

It is premature to assess whether prices are already seeing a war-related trend, but the data we have from DailyNK show a much more volatile year than in 2020. The regime admitted food problems in mid-2021 and then prices fell into the harvest. But prices are once again on a steady upward trend.

The international community—and China, as North Korea’s lender of last resort—are likely to once again face the long-standing humanitarian dilemma: to bail out a country not because of a natural disaster or the adverse effects of conflict but because of misguided political priorities. The moral imperative is clear, but as Becky Christofferson and I have shown, the political response to it has been blunted by aid fatigue and a declining willingness to come to North Korea’s rescue. The border closure and expulsion of aid workers during the COVID crisis will only amplify the problem. I hope I am wrong and that prices moderate or China rides to the rescue. But as a vulnerable country with a vulnerable population, North Korea could well be an unexpected victim of the war in Ukraine.

Thanks to Benjamin Katzeff Silberstein and Yeilim Cheong.

Stephan Haggard is a Non-Resident Fellow at the Korea Economic Institute and the Lawrence and Sallye Krause Professor of Korea-Pacific Studies, Director of the Korea-Pacific Program and distinguished professor of political science at the School of Global Policy and Strategy University of California San Diego. The views expressed here are the author’s alone.

Image from Shutterstock.