The Peninsula

New Sanctions Aim at North Korean Economy, Less so Missiles and Nukes

Won hold steady as gasoline prices soar, but for how long?

By William Brown

China and Russia watered down the new UN sanctions, imposed after North Korea startled the world with its apparent thermonuclear test September 3. However, their impact on the economy still could be severe, even crippling eventually. By accepting tough rules on textiles, joint ventures, and overseas employment, both former communist capitals seem to have tossed out their previous, probably pretend, concerns for the well-being of the people and aimed squarely at the general economy.

Meanwhile, specific U.S. sponsored sanctions that would have disproportionately hit state enterprises and the government were denied, especially in the oil sector. Kim Jong -un predictably reacted to the outside world with more bluster and yet another intermediate range missile test over Japan on September 14. But we don’t know as much about what he and his circle of leaders are thinking and doing domestically, something probably of far greater importance.

One thing is for sure; big adjustments in economic policy are needed if he is to maintain progress on the two byongjin fronts—the nuclear program and economic growth. If he isn’t careful, inflation caused by commodity shortages will come roaring back to crack what remains of his command, or fixed-price economic system. This would undo what so far has been Kim’s crowning domestic achievement, getting a handle on a monetary system left in chaos by his father and grandfather (see byongjin blog). As the leadership learned in a monetary panic in 2009, just as young Kim was being prepared to take over the government, nothing will bring people, even North Koreans, to the streets faster than an assault on their money. And if true nearly ten years ago, it is far more important today given the wide expansion in the use of money and markets that is contributing to economic growth.

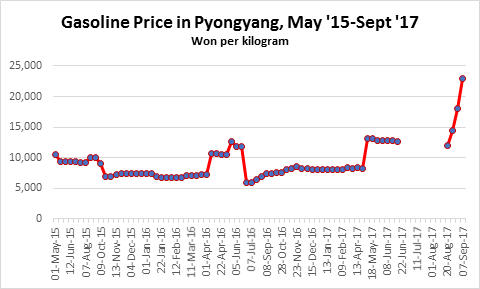

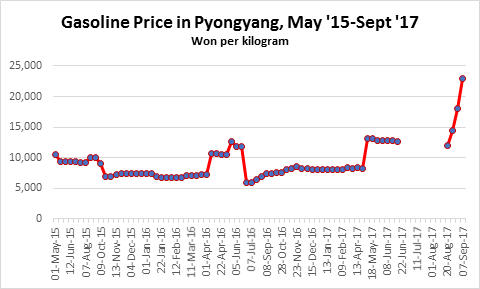

If Kim needs any reminders of this predicament, all he needs to do is look down the street. Diplomats, and Daily NK reporters are saying the price of gasoline in Pyongyang has nearly doubled just in the past three weeks. A kilogram of gasoline is reported to cost W23,000 on September 9th, the equivalent of about $8 a gallon at the widely used black market exchange rate, up from W18,000 at the beginning of the month, W14,000 in late August, and 8,000 won in January. Unlike a price jump in April, this time taxi and auto activity in Pyongyang is said to being impacted, and business is slowing. Likely even more concerning to the government are similar jumps in diesel and kerosene prices, just as the important and fuel-intensive harvest season is beginning. Diesel is widely used in portable generators providing essential electrical services in Pyongyang as the national grid supply remains unreliable. Complaints are bound to be rising, especially among the newly enriched entrepreneurial classes who need electrical generators to pump water for their high-rise apartments.

Petroleum though might be among the least of Pyongyang’s new concerns. The price jumps occurred despite what appears on paper very modest oil sanctions, suggesting prices may come down if the inflow is not actually squeezed. The U.S. had hoped for an embargo of Chinese crude oil deliveries though few expected that would happen. Instead crude oil will continue at its historic rate of about 4.4 million barrels a year (about 600,000 tons) and will likely remain free to the North Korean government based on a secretive Mao-era aid agreement. (I argue elsewhere that ending this aid is the key to pressuring Pyongyang.) Refined petroleum product sales to North Korea are capped at 2 million barrels a year, 500,000 barrels a quarter beginning in October, slightly less than the 2.2 million barrels China exported last year, but more than what China reports as having provided through July of this year.

Apparently, as reported by western news agencies, foreign exchange shortages are squeezing the North Korean importers so Chinese suppliers, such as the giant China National Petroleum Corporation, are withholding normal export credits, this was occurring even before the new sanctions. If so, it may be that finance, rather than sanctions, will be the limiting factor on oil deliveries. The U.S. government, on the other hand, asserts Pyongyang imports more than twice what North Korea’s trade partners admit to selling North Korea and that somehow all of this will be subjected to the 2-million-barrel a year cap. This would mean that the total annual petroleum supply from all sources would fall from about 8 million barrels to about 6 million, a significant but not a drastic drop, and it would save Pyongyang precious foreign exchange.

Much more damaging to North Korea would be a collapse in the NK won, and attendant inflation, a logical outcome of the new embargos on North Korean textile and apparel exports and fish products. According to Chinese customs, textiles have risen from almost nothing ten years ago to $330 million in the first seven months of this year. This is already down about 20 percent from the same period in 2016 and, if the sanctions are enforced, will drop to nothing in coming months. The foreign exchange cost to North Korea will be much less than that, since North Korea imports more textile related materials from China than it exports and much of these will no longer be needed. Still, the disruption to the industry, one of the country’s largest employers, will be severe. In recent years, textile factories have retooled to serve the export market and now will have switch back to a much less viable domestic market. Workers in the large, unproductive state factories will be generally unaffected but thousands, maybe tens of thousands of productive workers not in the socialist system will be forced out of their private or foreign joint venture workplaces. Many may try to go to China where factories will be in even greater need of cheap labor, but the new overseas employment restrictions will make that hard to do, at least legally. How the regime responds to this soon to be hard-hit labor and export intensive industry should thus be watched very carefully.

This weekend diplomats in Pyongyang reported that about W8,000 will still buy a dollar in local exchange markets, no change from over the past few years, making the dollar price of gasoline among the highest in the world. This stability is remarkable given the drop in exports, and indicated further drops on the way. But here again North Korea, and its half-market, half-command economy is anything but normal. This stability is probably the result of extreme caution in providing new credit, effectively preventing new investments, or wage increases for impoverished state workers, and in allowing foreign currency, U.S. dollars, to invade the economy at all levels. Pyongyang may even be intervening in the new foreign exchange markets to support the won, expending precious dollars to do so. North Korea, quite amazingly, thus seems on its way to becoming a dollarized or currency board type economy, one in which the government has little control over the money supply, the banking system, and even its own budget. If North Koreans are like people the world over, and there is no reason to think they are not, once a small break in the value of won occurs, they will panic and sell their won for available dollars in a downward, self-realizing, spiral. The government knows this and is valiantly holding the line.

Sooner or later we can expect the rate to crack, just like ancient Korean houses in Ryanggang province reacting to the September thermonuclear explosion. How then will the young Marshal respond?

William Brown is an Adjunct Professor at the Georgetown University School of Foreign Service and a Non-Resident Fellow at the Korea Economic Institute of America. He is retired from the federal government. The views expressed here are the author’s alone.

Photo from Roman Harak’s photostream on flickr Creative Commons.