The Peninsula

Mapping Kim Jong-un’s Appearances, 2012-2021

There is a long tradition of considering North Korean leaders’ public appearances as a potential source of information on the regime’s priorities (see for example: Haggard, Herman, and Ryu; Pyo and Hur; Kim and Lee). We now have ten full years of this data for Kim Jong-un through the South Korea Ministry of Unification portal, covering 2012 to 2021 and encompassing 1,231 discrete events. These appearances take a variety of different forms, but fall broadly into two categories: attendance at formal meetings; and so-called “on-the-spot guidance” or OSG visits to military and work units and other sites.

We coded these on two key dimensions: where the visits took place and the sector and purpose of the appearance. Well before COVID, Kim Jong-un’s mingling with the people had waned significantly. In terms of priorities, we see an early focus on the economy gradually give way to more military visits, and among those the missile and nuclear programs getting more attention than conventional forces. During COVID, however,—and particularly in 2021—Kim Jong-un was housebound in Pyongyang. His appearances were increasingly focused on politics and official meetings rather than the types of guidance visits that were staples of his grandfather’s approach.

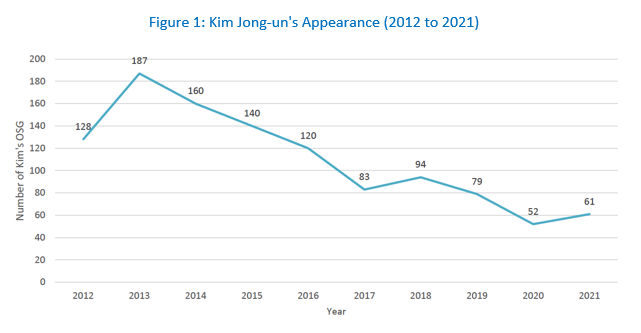

Before turning to the location and purposes of these visits, Figure 1 maps total public appearances by year. Kim Jong-un’s use of OSG trips peaked early in his rule—in 2013—and have declined steadily since, hitting a low as COVID struck.

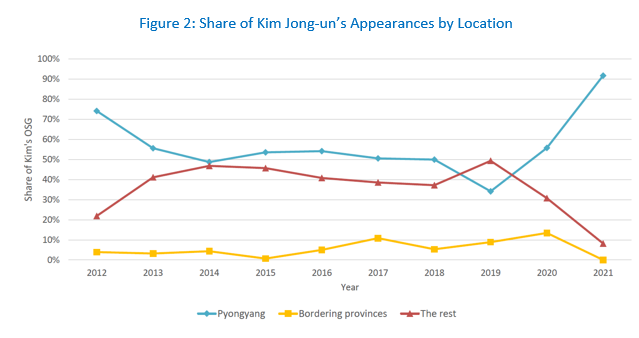

In terms of geography, we can divide visits by proximity, distinguishing between Pyongyang, the provinces—including special cities—that border Pyongyang (Nampo, South Pyongan and North Hwanghae) and what might be called “the rest”; these are graphed in Figure 2. Not surprisingly, he stayed close to home in his first year in office, with a large majority of his appearances, including OSG visits, in Pyongyang. He subsequently divided his time roughly equally between Pyongyang and the other provinces, even in 2020. However, two points are worth noting. First, appearances outside Pyongyang and the neighboring provinces are extremely limited. And second, in 2021 his public appearances were almost entirely in Pyongyang. The capital has loomed larger and larger in Kim Jong-un’s schedule.

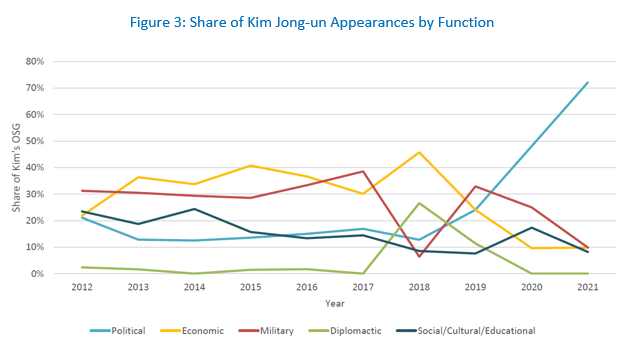

With respect to function we coded the visits into several categories, starting with the political: these include both government and party meetings and more ceremonial political events such as national anniversaries, memorial and birthday services and visits to family. The remainder of visits are coded into four additional locations and purposes: economic; military; diplomatic; and social, cultural and educational appearances. As can be seen in Figure 3, in the first five years of his rule, economic visits edged military ones, but then seesawed in 2017-18. The tensions on the peninsula in 2017 were accompanied by an uptick in the share of visits to the military. But the onset of summit era saw a quite dramatic fall in military visits and a surge of diplomatic appearances before military appearances rebounded again in 2019-20. But what is striking is that being confined to Pyongyang as a result of COVID led to sharp increase in political appearances, dominated by formal meetings.

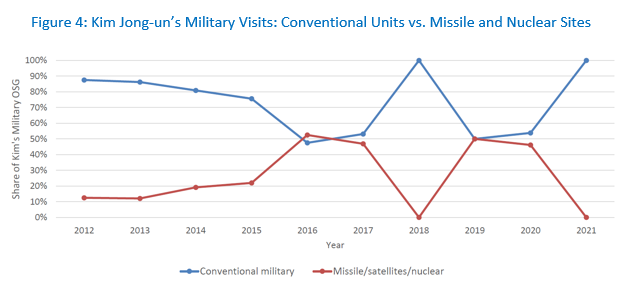

As the number of visits falls, parsing them into finer and finer categories runs risks. However, it is interesting to divide Kim Jong-un’s military visits into those to conventional forces units and those related to the missile and satellite programs and the very small number of times (in 2016-17) when he made visits identified with the nuclear program (Figure 4). In the early days of his rule, it was particularly common to see Kim Jong-un appearing at conventional military units and mugging with adoring soldiers. Yet except for 2018—when the missile and nuclear program was downplayed—the growing share of those visits rightly captures the regime’s investment in the nuclear and missile programs.

As with all efforts to understand North Korea—from reading satellite images, to shards of economic data, to speeches, to information of this sort—nothing standing alone will tell a compelling story. But several things appear to stand out from this exercise. First, the early “man of the people” image, with frequent appearances and OSG visits, was already diminishing well before COVID struck. Despite the concerns about the economy associated with sanctions, then with COVID, economic OSG visits fall after their peak in 2018, not coincidentally the summit year. And even prior to COVID, Kim Jong-un tended to stay close to the capital city. Since COVID, his appearances have been confined almost entirely to Pyongyang and more and more take the form of chairing political meetings. Whether this adds up to a leader even more isolated from his people—or even concerned about political risks—is hard to say. But it is certainly one possible interpretation.

A note on the data.

The dataset is constructed from information from the South Korea Ministry of Unification; more detailed information about his OSG can be found at this portal. The original data has a total of 1,231 appearances. Yet, we ruled out some double-counted activities such as participating in photo sessions with event participants and watching concerts after the visits to the Kumsusan Memorial Palace. Accordingly, we used 1,104 appearances for this analysis. The MOU’s data consists of two parts: location of the appearance; and sector of the visited sites. The location data has several subcategories such as district, distance from the capital, and each city/county’s latitude and longitude. The sector data subcategories included economic, military, diplomatic, and social/cultural/educational events as we mentioned above. However, the coding is not based entirely on the site itself since Kim Jong-un tends to visit the same site with different intentions. With respect to his purpose, the Ministry of Unification of South Korea officially reports why he visited the site and what he did during the tour.

Finally, it is worth providing somewhat more detail on military visits. To classify whether an OSG visit by Kim Jong-un to the military sector is related to ballistic missile development, nuclear programs or just conventional military drills, we used information from the Beyond Parallel and the CNS North Korea missile test database. No doubt for intelligence reasons, there were only three nuclear-related OSG visits from 2016 and 2017 and they are worth noting: (1) on March 9, 2016 Kim Jong-un met scientists and technicians in the field of nuclear weapons research and provided guidance on the work to increase the nuclear arsenal; (2) on January 5, 2016, a day before the 4th nuclear test, KCNA reported that Kim Jong-un visited an unidentified artillery unit. Although his intention to visit the site was not specifically disclosed, we coded it as a nuclear-related OSG given its undisclosed location and proximity to the test; and, (3) on September 3, 2017, he provided field guidance for nuclear weaponization at an undisclosed location, the same day North Korea carried out the 6th nuclear test in North Hamgyong Province.

Danbee Lee is a Master of International Affairs student with a focus on international politics and Korea at the School of Global Policy and Strategy University of California San Diego.

Stephan Haggard is a Non-Resident Fellow at the Korea Economic Institute and the Lawrence and Sallye Krause Professor, Director of the Korea-Pacific Program and distinguished professor of political science at the School of Global Policy and Strategy University of California San Diego. The views expressed here are the authors’ alone.

Photo from kikodoze’s photostream on flickr Creative Commons.