The Peninsula

Lessons from the IMF Annual Meeting for South Korea

Every fall, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) hosts the world’s top economists, central bank officials, government bureaucrats, and civil society leaders in its Annual Meetings to discuss issues of key concern and calibrate a future outlook on the global economy. There were four main themes in this year’s meeting: moderating inflation, low growth, fiscal stress, and geopolitical risk. As managing director of the IMF, Kristalina Georgieva noted during her speech:

“The big global inflation wave is in retreat… without tipping the global economy into recession and large-scale job losses. [But] higher price level… is here to stay… Even worse, we are in a difficult geopolitical environment…. And on top of it all, this is happening at a time when our forecasts point to an unforgiving combination of low growth and high debt – a difficult future.”

KEI has been following the macroeconomic trends on growth and inflation mentioned by Georgieva as they apply to South Korea. The South Korean government’s latest estimate shows year-over-year inflation at 1.6 percent, which is a remarkable achievement given that the latest US core inflation estimate stands at approximately 3.3 percent and South Korea was undergoing a seasonal elevation in prices during the month of September. At its peak, global inflation stood at 9.4 percent in Q3 of 2022. The latest IMF projection shows global inflation reaching 3.5 percent by 2030.

During his visit to the Council on Foreign Relations (CFR) in New York ahead of this year’s Annual Meetings, the Bank of Korea (BOK) Governor Rhee Chang Yong mentioned three factors for South Korea’s success in taming inflation below the target rate of 2 percent. First, the BOK “started to raise [its] rate from mid-2021” due to a rapid rise in South Korean housing prices during this period, which was well ahead of the sharp increase in global inflation. Second, the South Korean Ministry of Economy and Finance (MOEF) also favored a “less expansionary fiscal policy during the inflationary period.” Finally, the BOK raised the base rate by 3 percent when inflationary pressures began to increase. South Korea’s success in lowering inflation without ushering in a recession means that the BOK can transition to an environment of lower interest rates that would relieve pressure on the debt-laden household sector and reinject more dynamism into the economy.

The Downside Risks

South Korea’s growth came down from a previous two-year high of 3.3 percent in Q1 to 1.5 percent in Q3 of this year. IMF estimates show global growth projected to be 3.2 percent in 2024. However, the IMF’s outlook also outlines at least four major threats on the horizon: 1) geopolitical risks arising from conflicts in the Middle East and Ukraine, as well as rising protectionism and trade policy uncertainty; 2) monetary policy staying too tight for too long; 3) financial markets remaining uncertain; and 4) deeper slowdown in the growth of the Chinese economy.

How to Manage?

To address downside risks, the IMF recommends that countries implement a “policy triple pivot” that includes loosening monetary policy, lowering government debt to recover the fiscal space for dealing with future crises, and pursuing structural reforms that improve growth prospects. None of these recommendations, however, are easy for policymakers.

Although the central banks are already leading the way in loosening monetary policies, there is always the challenge of properly timing interest rate reductions, which can lead to either a return of inflationary pressure or a recession. The BOK began monetary easing earlier this month by cutting rates by 0.25 percent. According to Governor Rhee, the market interest rate in South Korea began to move down as early as July due to expectations that easing by the US Federal Reserve System would trigger a downward shift in South Korea’s interest rates. However, he also signaled that concerns about the macro-financial condition were an important factor impacting the speed and size of the BOK’s monetary easing. The Bank of Japan Governor Ueda Kazuo voiced similar concerns about the size and speed of adjustments in Japan’s monetary policy. These signals suggest that central bank vigilance, along with close international consultation and coordination, will continue to play an important role in implementing the right kind of monetary policy.

Regaining the fiscal space requires sound fiscal policy backed by a fair and efficient system of spending and revenue collection. Much of the discussion in this year’s meetings focused on the revenue side of the equation, with proposals on taxes for the super rich, better governance to reduce corruption and tax evasion, broadening the tax base, and making the tax system more simple, convenient, and intuitive. The challenge, however, rests with the political viability of these recommendations, given that policy proposals to raise revenue are unpopular.

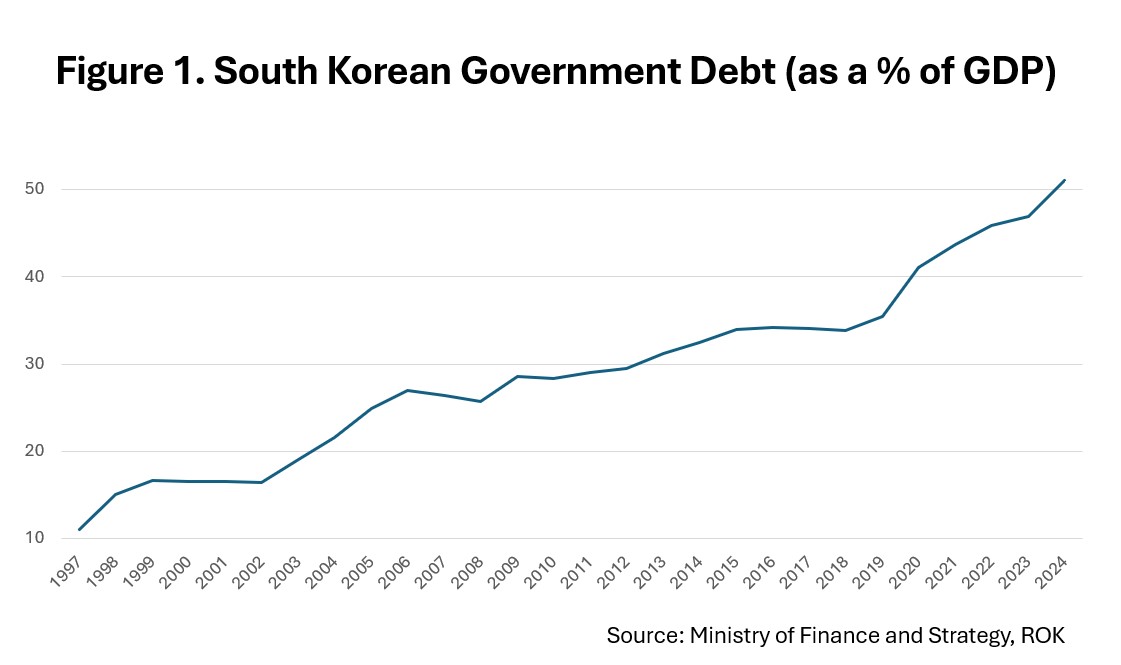

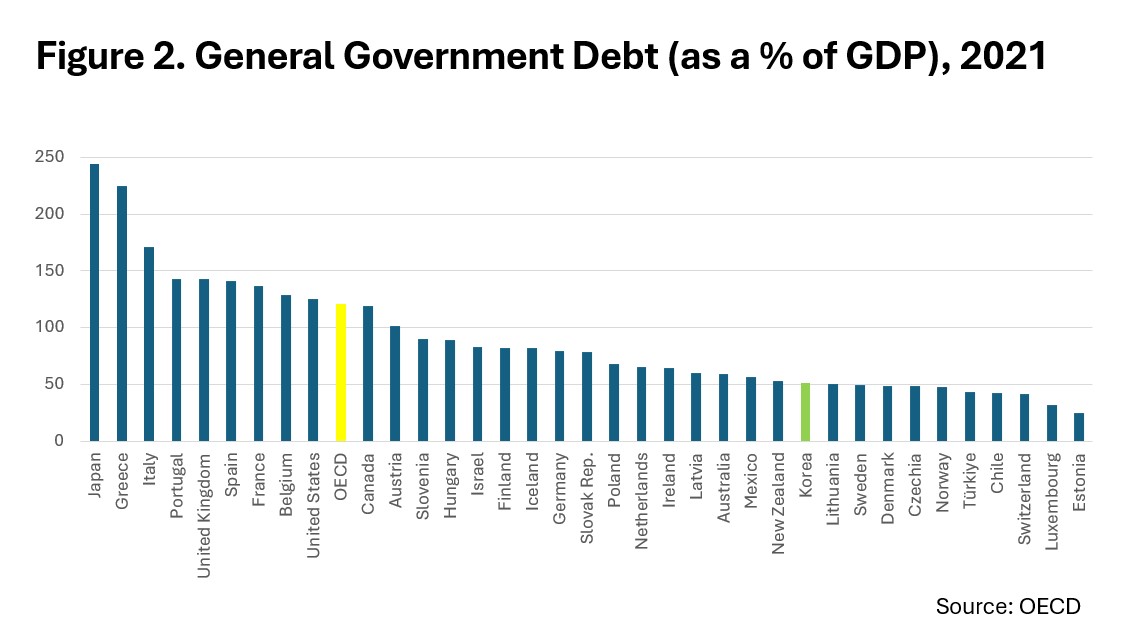

While the latest data issued by MOEF shows a continued increase in government debt and spending (Figure 1), the overall situation looks less alarming than in other countries around the world. Comparative data shows that government debt as a percentage of GDP is below the OECD average (Figure 2). However, South Korea’s household debt is still higher than most countries, and there are structural challenges associated with the country’s low birth rate and aging population. If South Korea is unable to find a solution to these problems, fiscal stress is likely to worsen over time.

Finally, South Korea should take a more proactive approach to address the issue of over-reliance on trade with China. One of the issues highlighted during the IMF meetings by the chief economists of major international financial institutions pointed to concerns about a protracted and deeper slowdown in China’s growth that could weigh on the global economy. While outlooks differed about the future prospects for China, all experts agreed that structural reform would be necessary.

This brings us to the last policy recommendation by the IMF, which focused on the need to institute structural reforms that would improve competition, facilitate resource allocation to emerging sectors, and strengthen labor supply. Here again, however, policymakers will have to address the problem of public buy-in for change of this kind. The IMF recommends effective communication strategies that are tied to securing explicit electoral mandates, extensive communication with key stakeholders (i.e., trade unions and business associations), testing pilot cases, and using comparative policy research.

These issues are hardly unique to South Korea, but one solution is to come up with a better policy toolkit for promoting growth through quality research and continued consultation with other countries. Being able to engage more constructively with different societal and economic interests would also prove critical, even though there is a history of contentious relationships between business and various civil society interests. As Georgieva noted at one point in the meeting, continued reliance on trade may no longer be a viable option given that “trade, for the first time, is not a driver of growth but it is a follower…. in this environment, it is so very important that we concentrate on the number one priority, which is boost growth and deal with that responsibly.”

Looking Ahead

The IMF meetings this year charted a difficult road ahead for the global economy. While South Korea has fared well in lowering inflation, the BOK must remain vigilant so as not to keep rates too high for too long. Risk is tilted to the downside due to overly exuberant financial market conditions and heightened geopolitical tensions in the Middle East and Ukraine. Without governments being able to achieve fiscal prudence, a shock to the system can be unmanageable. While South Korea has taken proactive steps to address tax shortfalls and the country’s fiscal condition looks good for now relative to other countries, structural challenges arising from an aging population and geopolitical competition between the United States and China pose a significant threat. Continued reliance on trade must be tempered with structural reform and fiscal prudence.

Dr. Je Heon (James) Kim is the Interim Director at the Korea Economic Institute of America (KEI). The views expressed here are the author’s alone.

Photo from Shutterstock.

KEI is registered under the FARA as an agent of the Korea Institute for International Economic Policy, a public corporation established by the government of the Republic of Korea. Additional information is available at the Department of Justice, Washington, D.C.