The Peninsula

Korea’s Falling Birthrate Raises Concern

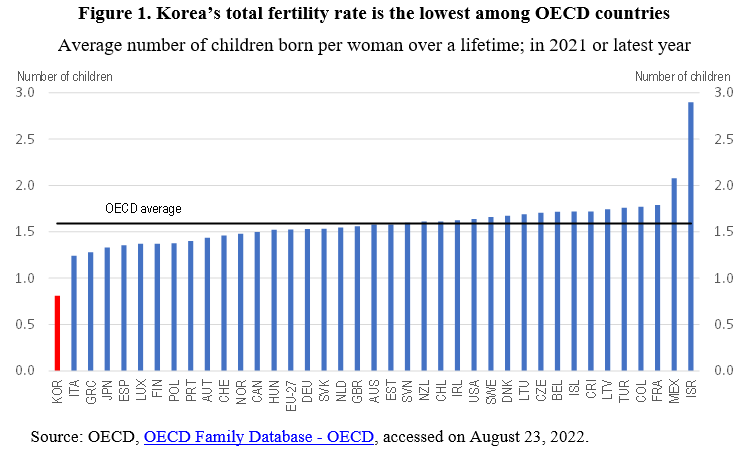

The steep decline in Korea’s fertility rate has created concern. In 2020, the number of deaths exceeded the number of births for the first time, according to census data from the Ministry of Interior and Safety. The Ministry stated that “amid the rapidly declining birthrate, the government needs to undertake fundamental changes to its relevant policies.” The fertility rate, which was 6.0 in 1960, was 0.81 in 2021, only half of the average of the 38 OECD countries (Figure 1). The latest decline may have been partly due to COVID-19. The Bank of Korea stated that the pandemic would exert “a negative impact on the nation’s marriage and birthrate, leading to an acceleration of aging in the population.”

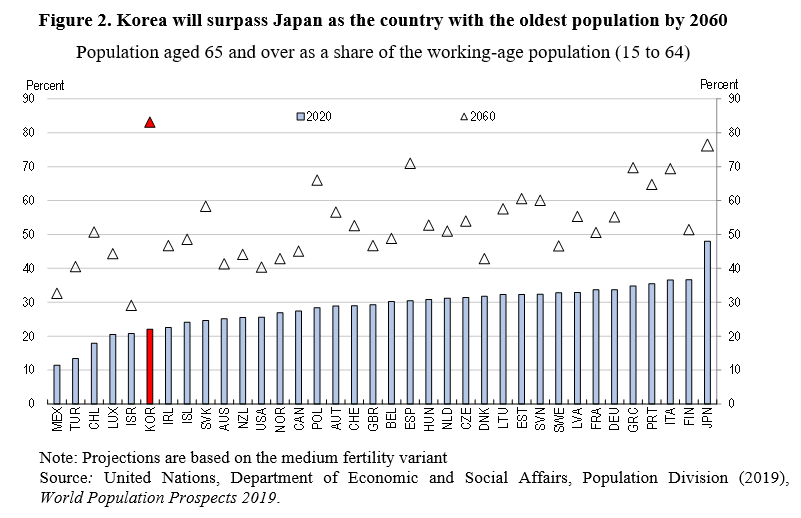

The low birthrate, combined with rising life expectancy, is projected to sharply increase Korea’s elderly dependency ratio (the elderly as a share of the working-age population). In 2020, Korea’s ratio was the sixth lowest among OECD countries, but is projected to be the highest in 2060 at 83% (Figure 2). In other words, the number of working-age persons per elderly is expected to fall from 4.5 to 1.3. The demographic transition is likely to pose serious socio-economic issues, including high fiscal costs.

Government policies to boost the birthrate

Korea has implemented a number of “Basic Plans on Low Fertility and Aging Society” since the mid-2000s to counter the fall in the birthrate.

- The First Basic Plan (2006-10) introduced measures to promote work/life balance, provided financial support for childcare for low-income families and strengthened employees’ rights for maternity and parental leave. In addition, it provided financial assistance for infertility treatment and medical assistance for pregnant women.

- The Second Basic Plan (2011-15) included the introduction of free childcare services for all families regardless of their income level. However, capacity did not increase sufficiently to accommodate all children, forcing some to rely on more expensive private care. Still, public spending on early childhood education and care increased from 0.1% in 2001 to 1.0% by 2016, a figure exceeded by only the Nordic countries and France.

- The Third Basic Plan (2016-20) aimed to boost families’ standard of living by addressing the high cost of housing and education. In addition, a child allowance of KRW 100,000 (USD 75) per month per child up to age six was introduced in 2018.

- The Fourth Basic Plan (2021-25) provided a monthly bonus of KRW 300,000 (USD 225) to families with children under 12 months starting in 2022, with it rising to KRW 500,000 by 2025. Couples expecting a baby receive a KRW 2 million cash bonus starting in 2022, and the KRW 600,000 medical expense support for pregnant women was increased to KRW 1 million.

Korea stands out in international comparison by allowing employed mothers and fathers covered by the Employment Insurance System to each take up to 12 months of paid parental leave. However, the take-up has been relatively low, especially for fathers. In 2018, less than 100,000 parents claimed the parental leave benefit – roughly 30 parents per 100 live births. Mothers accounted for 82% of the total, as Korea’s intense work culture tends to discourage fathers from taking leave. In contrast, in Germany in 2016, there were roughly 94 mothers and 35 fathers claiming parental leave benefits for every 100 live births. To encourage more fathers to use parental leave, Korea introduced a so-called “Daddy Month” in 2014 and extended it to three months in 2016. Under this rule, if both parents take parental leave, the second parent (usually the father) can claim a higher benefit for three months. In 2019, the benefit was increased to 100% of the parent’s earnings up to a ceiling that is equivalent to about 60% of average full-time earnings.

Changing social views have affected the fertility rate

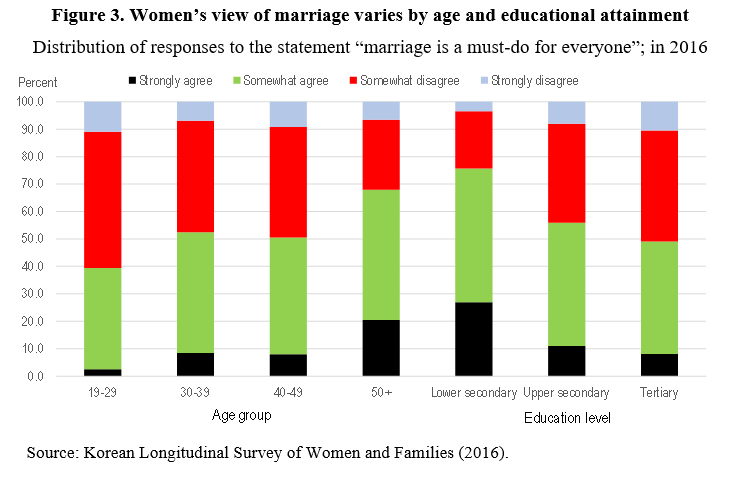

The increasing financial benefits offered for children, however, have not achieved the desired increase in the fertility rate in the face of shifting views about family and marriage. Among women aged 50 and above, a 2016 government poll found that two-thirds agreed that “marriage is a must-do for everyone” compared to less than 40% for women aged 18-29 (Figure 3). The average age of women at first marriage has increased significantly from 24.8 years in 1990 to 30.8 years in 2020. In addition, the marriage rate has fallen by half since 1980. Delayed marriage and the increasing share of women who remain single has a major impact on the fertility rate, as less than 2% of births occur outside of marriage in Korea.

The importance attached to marriage is lower for women with higher education (Figure 3), who account for a rising -share of the population. In the 25-29 age group, the share of women who are university graduates surpassed men in 2012 and is now 9 percentage points higher. As higher education has increased labor market opportunities for women, traditional family roles have less attraction for many women. Mothers in particular have been expected to devote significant time to the education of their children, which is difficult to combine with a full-time career. In addition, women continue to shoulder most of unpaid work – housekeeping and childcare. Indeed, women spend an average of 3.5 hours per day compared to 49 minutes for men. Consequently, there is significant pressure on women to leave the labor market once they have children. Highly-educated women in particular tend to postpone having children in view of the large opportunity cost or remain childless.

Many youth appear pessimistic about their prospects

Moreover, a significant share of young people appear frustrated by the challenges of education, employment and housing. Young Koreans are often referred to as the “sampo generation,” which literally means “giving up on three” — dating, marrying and having children. Young people face tremendous pressure to gain higher education, which enables them to obtain regular employment and high wages, often viewed as a prerequisite for family formation. Such employment opportunities are most prevalent in large companies and in the government. Not surprisingly, two-thirds of young people (ages 13-34) want to work at large firms or the public sector. In contrast, only 4% want to work for small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), reflecting the exceptionally large productivity and wage gap between large firms and SMEs in Korea’s polarized economy. Indeed, employees at firms with 300 or more employees earn nearly twice as much as those at firms with 10-99 employees.

Higher education also reduces the risk of non-regular employment, which is precarious and relatively low-paid. In 2022, 42% of young people (aged 15-29) were non-regular employees. Hourly wages of non-regular workers are only 72% on average of those of regular workers. Moreover, the share of non-regular workers enrolled in social insurance systems, notably the National Pension System, National Health Insurance and Employment Insurance, as well as in corporate pension systems, is much lower than for regular workers.

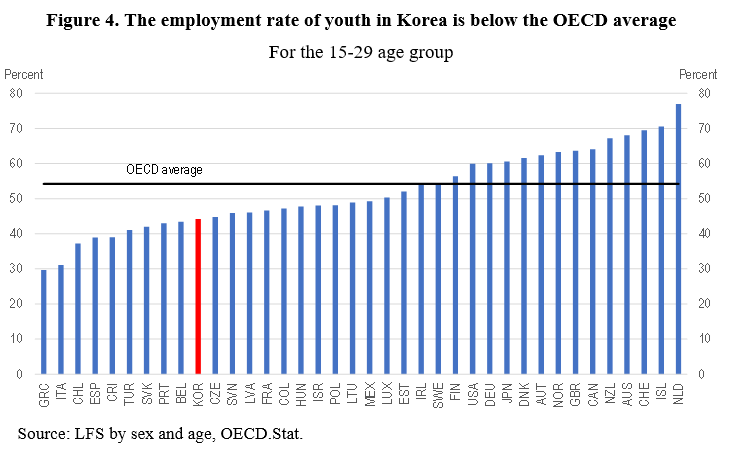

Labor market conditions contribute to the strong emphasis on education in Korea. Nearly three-quarters of high school graduates advance to college or university, which increases the chances of working in large companies and the public sector. However, large companies and the public sector do not generate enough jobs for the large number of tertiary graduates. Many young people queue for well-paid regular jobs, rather than accept SME and non-regular jobs, resulting in a youth employment rate that is significantly below the OECD average (Figure 4). Consequently, the rate of NEETs – persons who are neither employed, nor engaged in formal education or training – is relatively high among Korean youth, especially those who are university graduates.

Conclusion

The Korean government’s has taken steps in the right direction to boost the fertility rate by promoting work/life balance, providing free childcare and increasing public support for families. However, raising the fertility rate toward the OECD average (1.5 children) and the replacement rate (2.1 children) also requires fundamental reform of the Korean economy. First, it is essential to make it easier for women to combine employment and having children through further reducing working hours, sharing household work more equally and reducing the high costs related to education and housing. Second, Korea needs to reduce the dualism in the product market (between large companies and SMEs) and in the labor market (between regular and non-regular workers). This would boost youth employment and reduce income disparities, providing more young people with the financial foundation to create families.

Randall S. Jones is a Non-Resident Distinguished Fellow at the Korea Economic Institute of America. The views expressed here are the author’s alone.

Photo from Alexey Matveichev’s photostream on flickr Creative Commons.