The Peninsula

Korea Exported More Goods to the United States Than China in December—Does This Signal a New Trend for Trade?

For a twenty-year period, China had been the top export destination for Korean goods. Not so in December 2023, when Korea’s Ministry of Trade, Industry and Energy (MOTIE) announced that the United States had surpassed China to become Korea’s top goods export market on a monthly basis—marking the first time since 2003 that that was the case, according data compiled by Bloomberg.

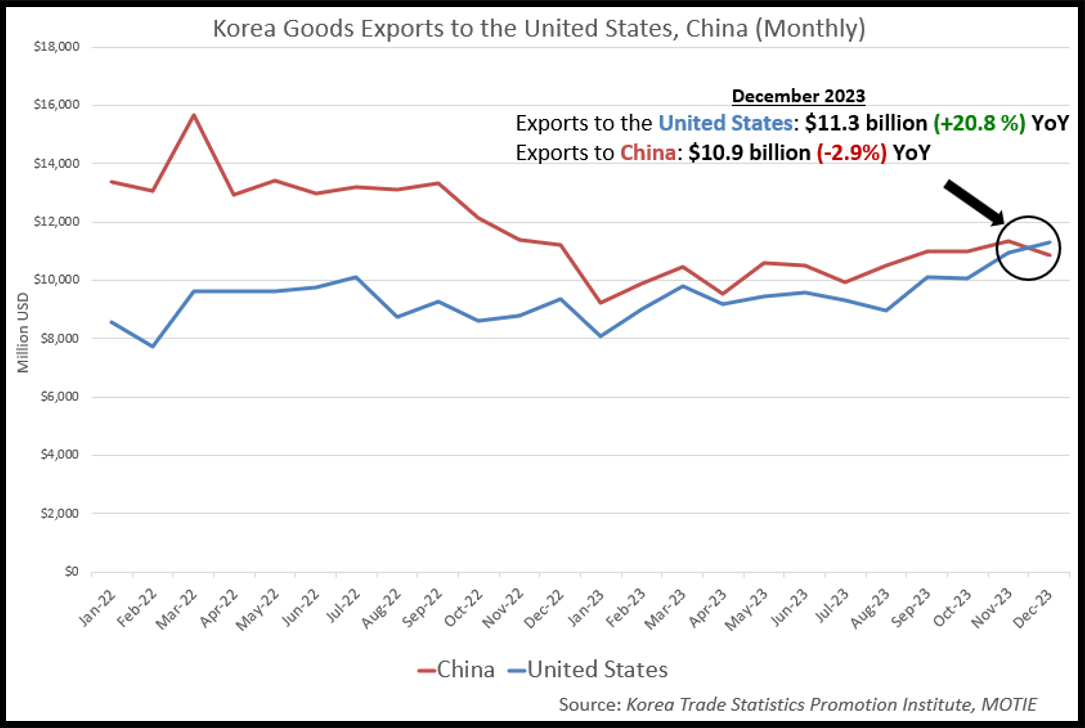

In last month’s trade figures stated by MOTIE, exports to the United States were at $11.3 billion, a 20.8 percent increase from the year before, while exports to China were at $10.9 billion, a 2.9 percent decrease year-over-year.

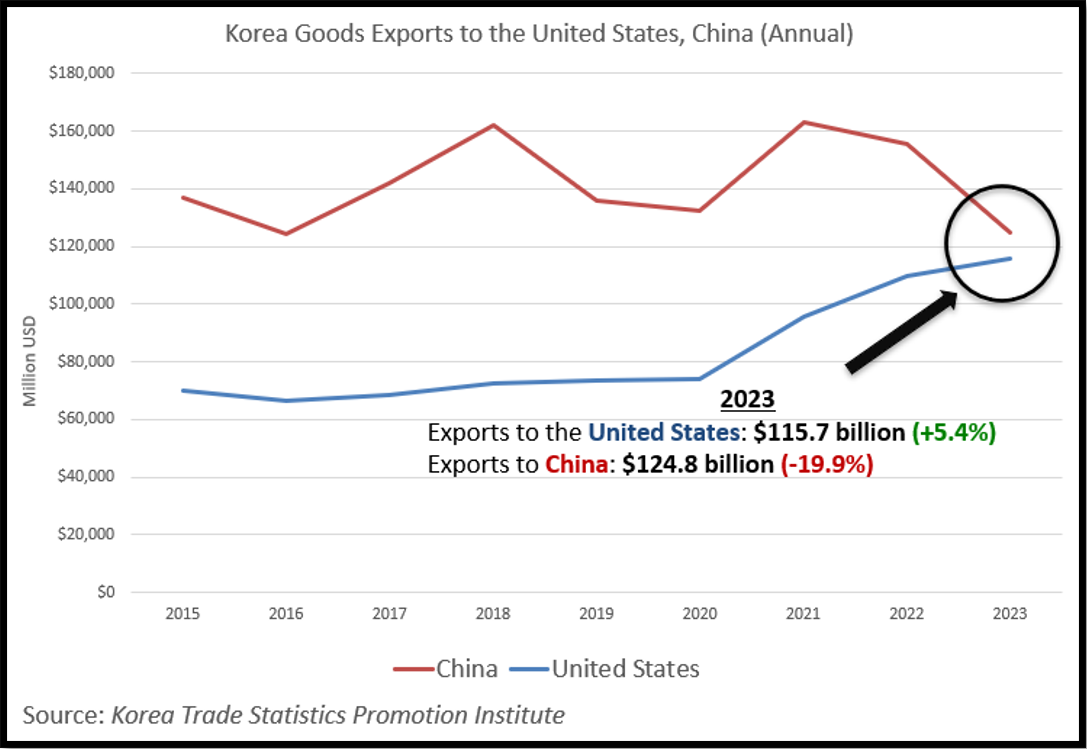

Volatility in Chinese appetite for Korean goods, as indicated by declining steel exports or recent periods of weakened electronics demand, may signify the effects of the slower than expected ongoing Chinese economic recovery from COVID. Alternatively, the U.S. side of things could represent payoffs from Korean investment in the U.S. market, where American demand for Korean cars, machinery, and storage batteries were heralded as champions of the increase. While Korea’s increasing exports to the United States were the driver of the change in monthly export rankings, Korea’s decreasing exports to China in 2023, at a near 20 percent drop, were the primary indicator of the United States gaining headway in the annual goods export figures—possibly clearing the way for an overtaking in 2024, should trends continue.

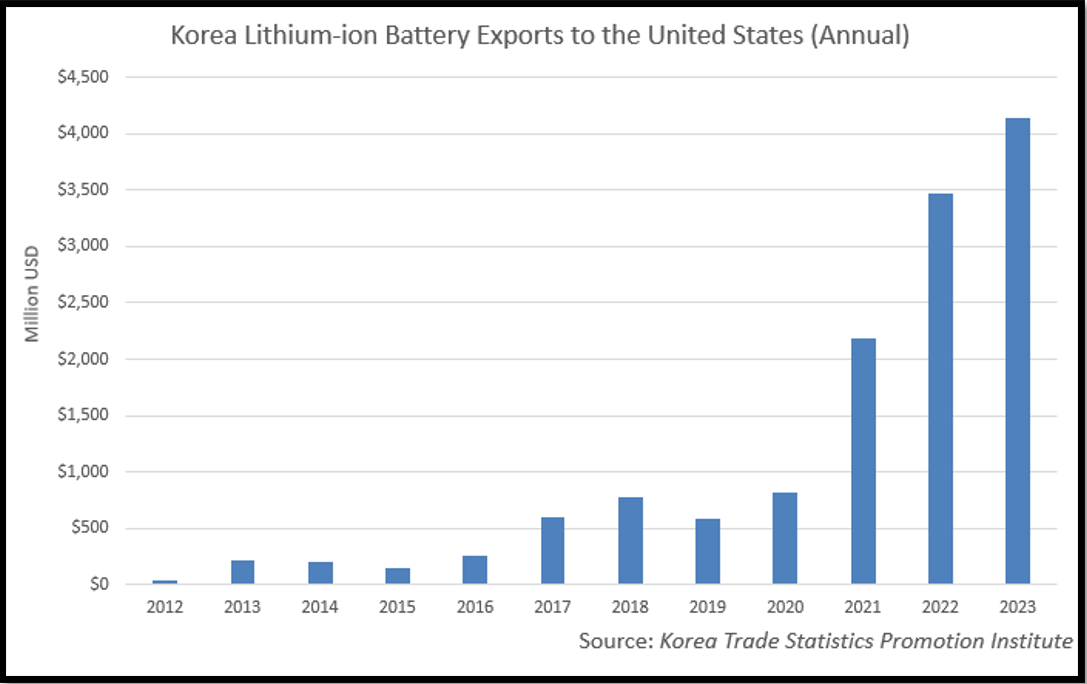

Consequently, Korean exports to the United States are slowly approaching China’s levels. Exports in lithium-ion batteries, which play a role in both consumer electronics and electric vehicles, have more than doubled from where they stood less than two years ago, and exponentially so from their rates prior to the COVID-19 pandemic. Korean passenger car exports to the United States have also accelerated steadily over the past decade, in part driven by eco-friendly car sales which now represent nearly one-third of all Korean vehicle exports.

In China’s case, a reduction in car imports from Korea demonstrates the opposite. Increasing popularity in domestic electric vehicle models such as BYD lends credence to the idea that import substitution measures are beginning to make a global comeback—especially as China becomes a leading global EV exporter in its own right. Similarly, for electronics exports, growing trends in technological dirigisme may increase efforts at domestic manufacturing of chips in China, as they seek to find alternatives to foreign chip production. For example, in part due to externalities from ongoing geopolitical competition between the United States and China, Korean chip companies suffered declining profits in 2023 as sales proportions in China for companies like Samsung shrank to single digits in some periods—although the recent overall Korean chips export stagnation has since ended with a rebound for both November and December’s export figures.

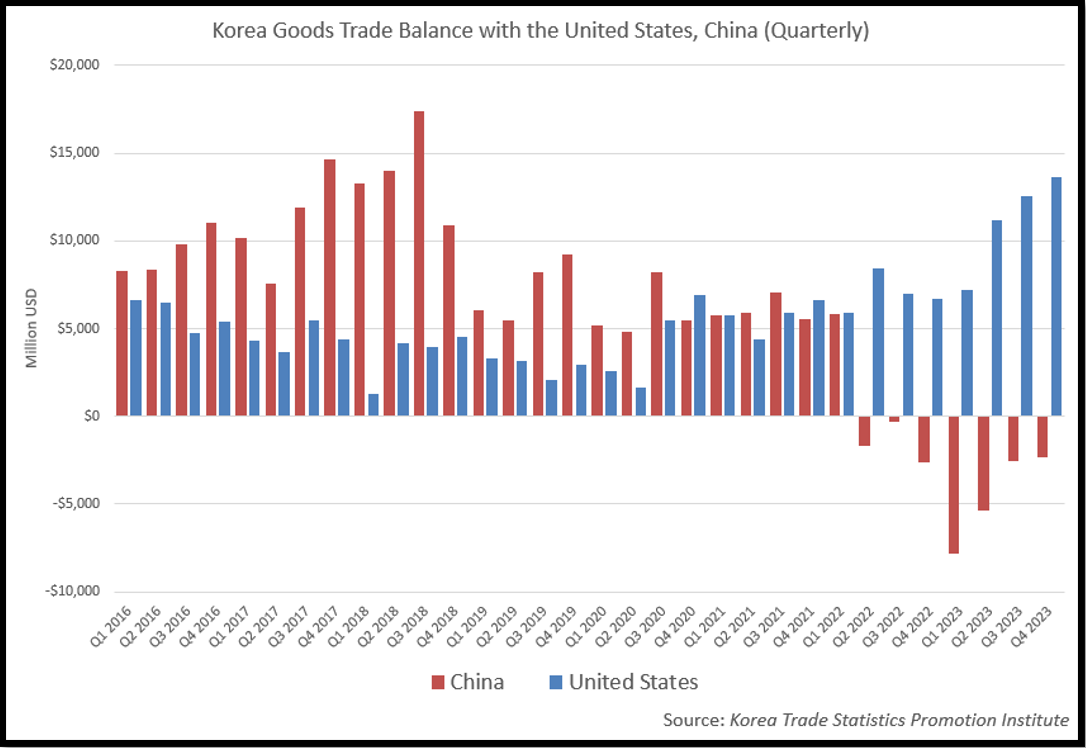

But the United States’ newly minted lead in Korean goods exports may ultimately only paint one part of the picture. On an annual basis, Korea’s services exports to the United States and China are competitive with one another. While unrevised 2023 data has Korean goods exports to the United States surpassing China by a marginal amount, once services are included, China may regain the lead in total exports. Similarly, Chinese inputs play a large role for major products such as electronics and batteries, and accordingly serve to tip Korea’s net trade balance (exports minus imports) in China’s favor. Indeed, Korea’s trade balance with China turned into a deficit for the first time in 31 years as imports surpassed exports. Although it is unclear what the long-term effects of U.S. restrictions on critical minerals and EV battery components from China under the Inflation Reduction Act may have on Korea’s imports from China, given this recent trade deficit, China is likely long to remain the primary total trade partner (exports and imports added together) for Korea as their geographical closeness continues to facilitate an ease of doing business.

What this means is that there is a still a long way to go before Korea’s changing trade patterns signal any change to their economic partnerships in the region. Born from their geographical closeness to the Middle Kingdom, Korea’s overall economic relationship with China remains much larger than its relationship with the United States. Consequently, trade with the United States would have to grow significantly before it could safely claim the total goods trade title from China.

Tom Ramage is an Economic Policy Analyst at the Korea Economic Institute of America. The views expressed here are the author’s alone.

Photo by Jean-Pierre Dalbera on Flickr.