The Peninsula

Just How Dependent is South Korea on Trade with China?

By Kyle Ferrier

China’s punitive economic measures against South Korea over THAAD may have shrouded Beijing-Seoul relations in uncertainty, yet they highlight Korea’s economic dependence on China. Throughout the extensive media coverage of impacted Korean companies as well as the regional geopolitical implications, particularly as they relate to the North Korean problem, is a common thread of economists suggesting Korea is too dependent on China for growth. While this is hardly a new development, recent events seem to be reinvigorating scrutiny of the size of bilateral ties. But, in the context of other global relationships how does this one stack up?

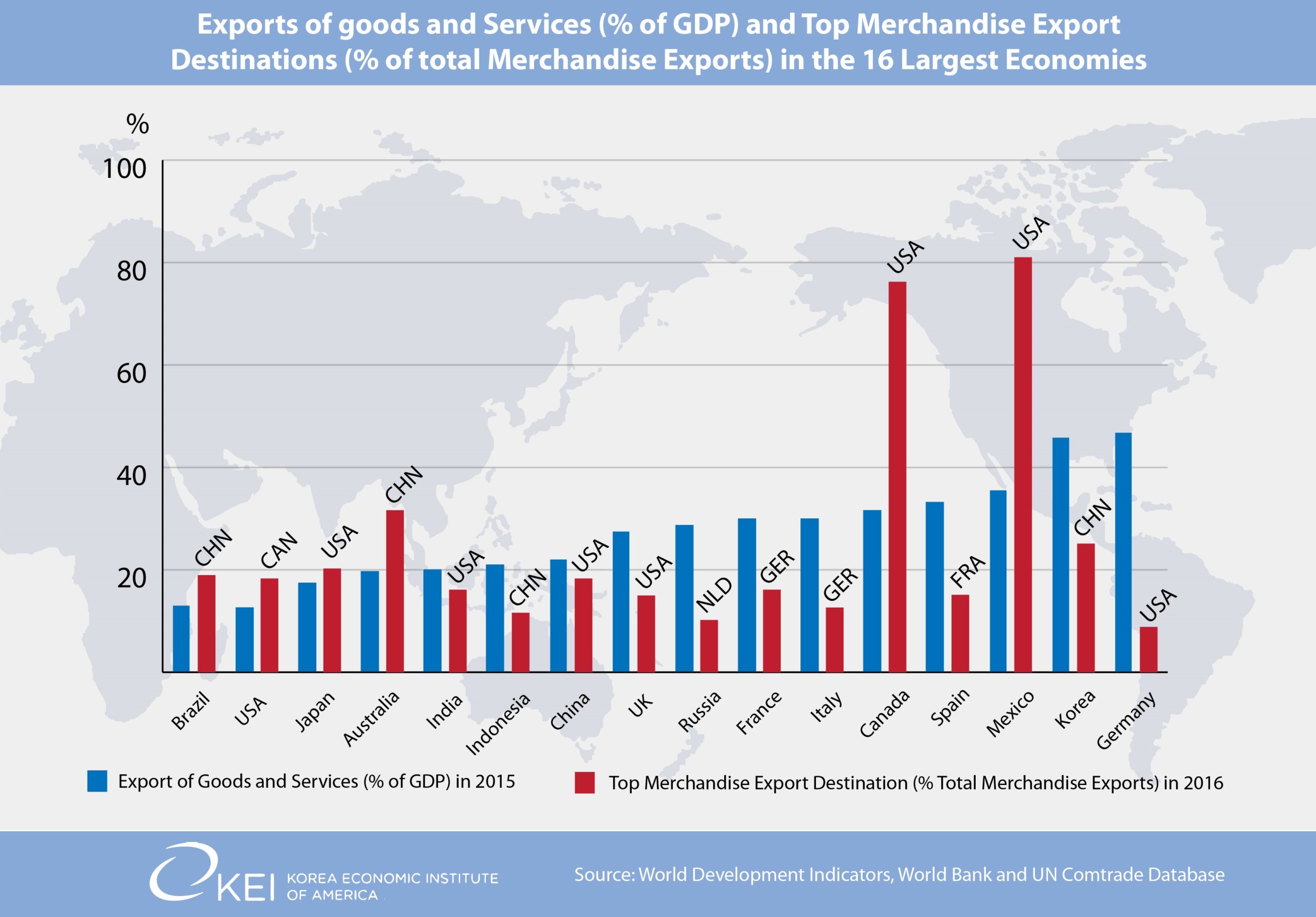

The Korean economy is reliant on trade for about half of its growth, making each large external relationship of crucial importance. Of the nearly $500 billion goods exported to the world last year, around $125 billion were sent to China, or a quarter of all exports, placing China at the top of Korea’s list of export destinations. Though both trade as a portion of GDP and the percentage of total exports sent to the top export destination are high, it is not a unique phenomenon, as shown in the Chart 1. In terms of GDP, Korea is the eleventh largest economy in the world. Among its peers in the top sixteen largest economies it is only just slightly behind Germany in terms of total exports as a portion of GDP. Korea’s exports to China as percentage of its total merchandise exports in 2016 is behind Australia’s 31.6 percent, but this pales in comparison to Canada and Mexico’s exports to the U.S., 76 and 81 percent of exports, respectively.

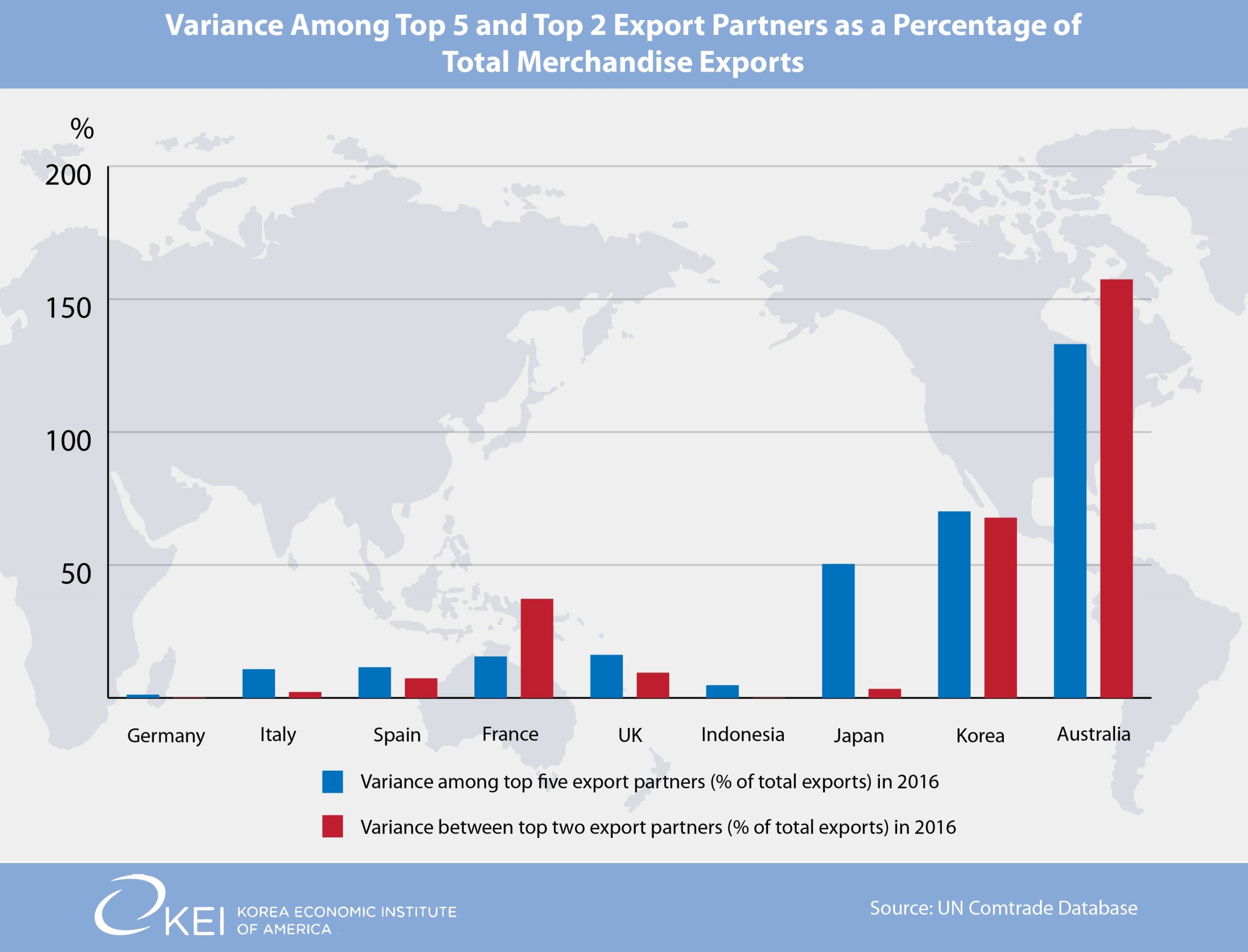

Chart 2 provides a complementary perspective. It measures variance in the share of total exports between the top two export partners and among the top five partners for a subset of countries from Chart 1. Or, in other words, it illustrates how spread out exports are. The first bar is reflective of the spread of exports to the top five export partners. The lower the bar, the less of a difference in the share of total exports between each partner, or the more equally distributed exports are. The second bar reflects the difference between the first and second ranked export destinations. The higher the bar, the bigger the drop-off between the share of total exports. This is also suggestive of the extent to which the first bar is driven by the top export market.

Chart 2 reveals exports for major European economies are more equally spread out than in major Asian economies, with the exception of Indonesia. It also reveals that within this group of Asian economies, Korea and Australia stand out for their dependence on exports to China. Although Japan may also have a more unequal degree of export concentration within its top five markets, the cause for this is divided between the U.S. (20.2 percent) and China (17.6 percent).

Yet more is revealed on how the Korea-China trade relationship compares to others if the charts are observed together. Korea and Australia may both heavily rely on trade with China, but Korea is nearly twice as dependent on exports for growth as Australia. While Germany is the closest to Korea in terms of exports as a percentage of GDP, exports are much more equally distributed among its top five trading partners. However, clearly absent from Chart 2 are Canada and Mexico, the inclusion of which would have dwarfed the differences between the selected Asian and European states due to their outsized trade ties with the U.S.

In essence, characterizing the magnitude of Korea’s trade dependence with China in a global context really depends on how it is framed. Compared to other large economies in Asia it is high, and to European countries very high, but in relation to North America is it is practically negligible.

Though the size of the relationship is important, so also is the composition of trade, especially considering why Korea-China economic ties are again garnering attention. Around three quarters of South Korean exports to China is processing trade, meaning goods are sent to China only to be assembled and then exported to a third country who is the ultimate driver of demand for these Korean exports to China. Australian exports to China on the other hand are driven by raw materials (i.e. HS codes 26, 27, and 71), composing nearly three quarters of all exports to China and are directly tied to domestic Chinese demand. During the past several months when Beijing has seen to be punishing South Korea over THAAD, Korean exports to China have increased, rising 10.2 percent year-on-year in April and 12.1 percent in March. While there is obviously still room for China to hurt the Korean economy, the fact that most Korean exports to China are tied to global demand limits the extent to which Beijing may influence economic ties on political grounds.

Kyle Ferrier is the Director of Academic Affairs and Research at the Korea Economic Institute of America. The views expressed here are the author’s alone.

Photo from SeoulHappyLife’s photostream on flickr Creative Commons.