The Peninsula

Is Korea Vulnerable to Democratic Backsliding?

A curious feature of advanced industrial states is anxiety about the future of democracy, not only abroad but at home as well. These worries—encapsulated in the concept of backsliding–have been particularly evident in the United States following the challenges posed by the Trump administration. The bruising fight over Brexit in Britain and the rise of new right parties on the European continent have generated similar concerns. Unambiguous cases of democratic regress in countries as diverse as Poland, Hungary, Turkey, Brazil and the Philippines have raised questions about newer democracies once thought immune from democratic regress.

South Korea is typically considered a democratic success story, and is headed into yet another presidential election in which a peaceful transfer of power is a virtual certainty. Nonetheless, a new, somewhat pessimistic discourse has emerged on the future of Korean democracy; a short bibliography of exemplary work in this vein is listed at the end of this post. This line of analysis is directed largely at the Moon administration and has come mostly from conservative analysts, but similar charges have been raised by those on the left about the Lee Myung-bak and Park Geun-hye governments.

In this post, I outline the concept of backsliding and some of the concerns that have been raised. I then at look data on the strength of Korean democracy from two respected and widely-used sources: the V-Dem project and Freedom House. They suggest a pattern quite at odds with critics of the current administration, namely that declines in assessments of Korea democracy—if any—seem more apparent under conservative administrations than liberal ones. Nonetheless, several charged examples, including the prohibition on cross-border balloons, a flawed media reform act, and the ruling party’s approach to the opposition all merit debate.

Backsliding: The Charge Sheet.

In contrast to the military coup or revolution, the distinctive feature of backsliding is that it emanates from duly-elected governments, often with substantial, although not necessarily, majority support. Once in office, elected officials undertake incremental measures—often difficult to assess at the time—which reduce horizontal checks on the executive, weaken civil and political liberties, and in the extreme, undermine the integrity of the electoral system. Although backsliding need not end in a transition to outright authoritarian rule, a number of the cases cited above are now rightly considered autocracies.

The worries about Korean democracy are multiple, but it is important to discriminate among them: we are not talking here about how the government has performed with respect to hot-button political issues such as North Korea or the property market; rather we are concerned about perceived derogations from democratic rule itself. The Korean political system has often been criticized for its “imperial presidency” and its weakly institutionalized party system. Yet charges of backsliding go further, getting at a “tyranny of the majority” approach to politics on the part of incumbents. These concerns arose after the 2017 presidential and 2018 local elections but particularly following the commanding majority the party gained in the 2020 general elections, when it took 180 out of National Assembly’s 300 seats.

Backsliding is associated with a majoritarian approach to democracy in which oppositions are gradually excluded from political power. In the wake of the Democratic Party victories, critics expressed concern about a decline in the inclusiveness of consultation and deliberation in the legislative process and about judicial independence; an example of the former is the distribution of National Assembly committee chairmanships. Conflict over the new Corruption Investigation Office for High-Ranking Officials (CIO) and the administration’s moves “to eradicate deep-rooted evils (적폐청산)” including through the establishment of related committees or task forces in government departments, raised fears of executive aggrandizement and a politics of revenge. The controversy over the launching of balloons by North Korean human rights groups as well as a proposed media law raised issues about civil liberties and free speech.

These institutional concerns have been nested in broader worries about affective polarization and intolerance toward political opponents. Such polarization goes beyond differences in policy platforms to a tribal identification and the characterization of political opponents as enemies or even traitors to the nation; while not constituting evidence of backsliding per se, my work with Robert Kaufman suggests it is a crucial precondition for backsliding to occur. Contrasting images of the Seocho-dong versus Guanghwamun protests and “wars” over trending search charts on major Korean portal sites like Naver (“실검전쟁”) surrounding the scandal of former Justice Minister Cho Kuk have come to symbolize sharp partisan divides, increasingly fed by a highly partisan information environment.

Some Data

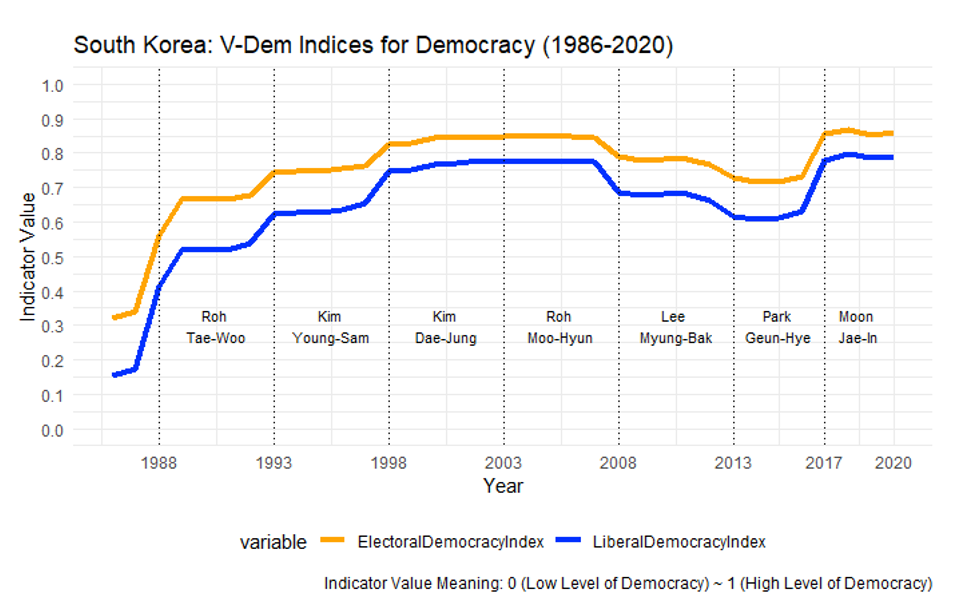

These concerns merit reasoned discussion, but such charges—whether leveled by right or left—might also be partisan; partisans are more likely to see challenges to democracy when they are in rather than out of power. To paint a wider picture of trends in Korean democracy over time, I draw on several well-respected cross-national datasets that provide a myriad of indicators on democracy. The electoral and liberal democracy indices from the V-Dem project provide a useful starting point. The electoral democracy index captures a more minimal conception of democracy and that weights free-and-fair elections heavily. The liberal democracy index by contrast includes the integrity of the electoral systems but adds in other factors such as the rule of law, the protection of rights and horizontal checks on the executive. Advanced industrial democracies typically score higher on the electoral than liberal democracy index but they are highly correlated.

For those who know the history of Korea’s transition to democratic rule, these measures make sense. Both indices jump sharply following the democratic transition in 1987-88 then rise steadily through the Roh Tae-woo and Kim Young-sam governments before plateauing at a level under Kim Dae-jung and Roh Moo-hyun that is almost exactly equal to the average of the European Union democracies. These measures then begin a gradual slide over the course of the Lee Myung-bak and Park Geun-hye administrations, reflecting a succession of derogations that Ariel Croissant has noted were “near miss” backsliding episodes. These include the unlawful government surveillance and blacklisting of opposition members and artists who were critical of the government, the National Intelligence Service (NIS) interference in the 2012 elections, Park’s role in Saenuri candidate nomination for the 2016 legislative elections and the plethora of departures from the rule of law that ultimately led to her impeachment. According to this data, the Moon Jae-in government is marked by an improvement in Korea’s democracy scores, and to levels which actually exceed that achieved under the Kim Dae-Jung and Roh Moo-hyun years (and which actually exceed those of both the United States and EU).

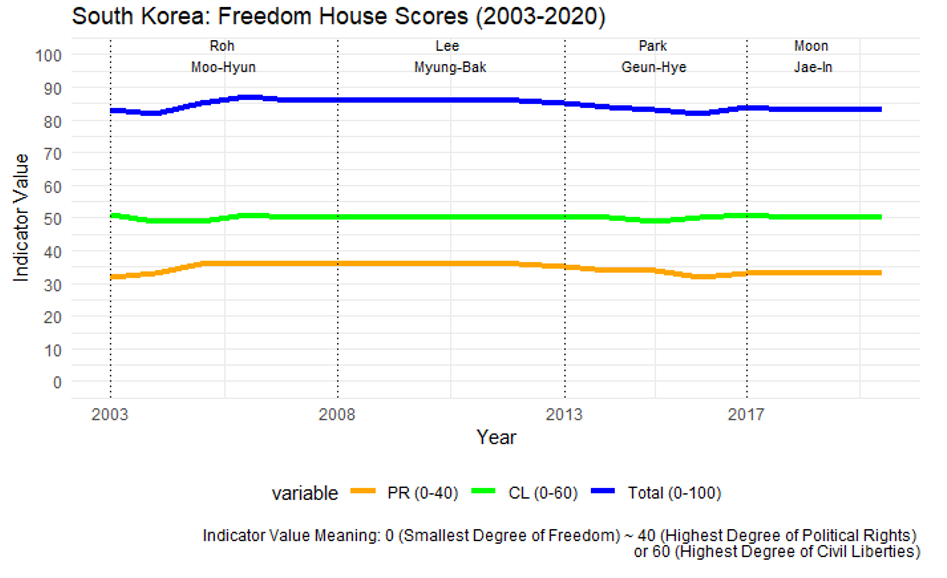

Students of democracy typically distinguish measures designed to capture the level of democracy tout court—such as those from the V-Dem project—and more narrow measures capturing one important component of it: the extent of the protection of political rights and civil liberties. Freedom House has long been the go-to source for these measures, providing indexes of both political rights and civil liberties based on a number of discreet components, such as rights of free speech, assembly and media freedom. The data is available in this particular index format for a shorter period than the V-Dem data. But despite concerns of democratic erosion, South Korea has remained well within the range of the category of so-called “Free” countries since its democratic transition. We do see some evidence of deterioration under Park Geun-hye before scores increase marginally under Moon Jae-in, albeit just below those in the Lee Myung-bak government. But despite these changes, the broader picture suggests a stability over the period in the level of protection of political rights and civil liberties.

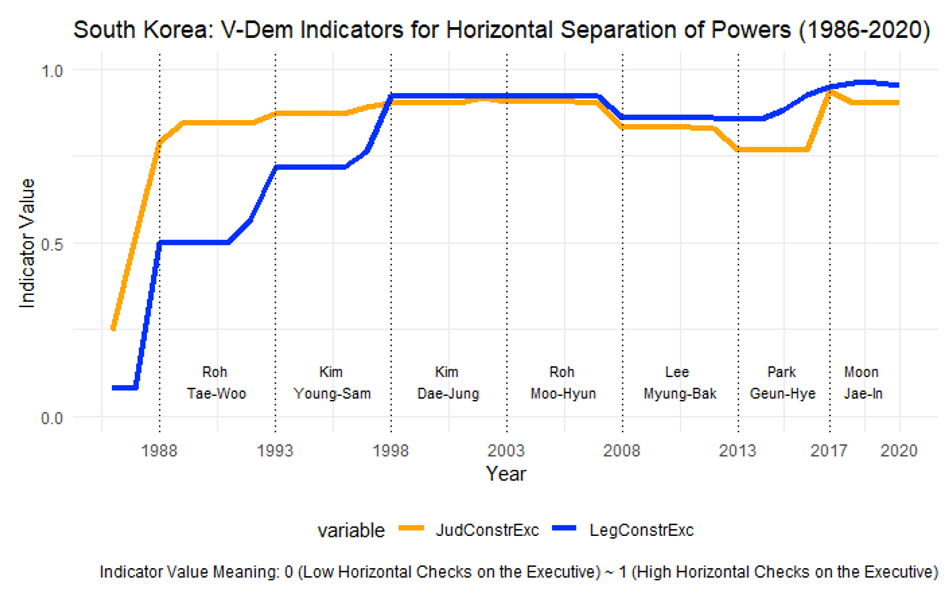

Just as we can disaggregate democracy from its political rights and civil liberties components, so we can also look at measures of the extent to which there is a horizontal separation of powers in which the legislature and judiciary operate independently of the executive. As noted, the strength of the Korean presidency has been a leitmotif of the study of the country’s politics. Yet we should not confuse a strong presidency with an actual collapse of the separation of power visible in more openly authoritarian regimes.

The storyline broadly replicates the V-Dem indicators of democracy. The separation of powers strengthened following the transition to democratic rule and was first evident in the increasing powers of the judiciary prior to the National Assembly playing a more active role. By the time of the Kim Dae-jung government this measure was converging on advanced industrial state norms (as with the wider index, roughly equal to the EU average and only marginally below the United States). The separation of powers—particularly with respect to the judiciary–underwent some deterioration under the Lee and Park governments. But the independence of the National Assembly actually increased in the late Park years as it asserted itself vis-à-vis her failing presidency. As with other indicators, prior levels of these variables were restored with little subsequent movement under Moon Jae-in through 2020 and perhaps even a marginal improvement; as with the broader democracy indices, Korean scores on this horizontal accountability index even exceed the EU and the United States.

Conclusion: Defending Democracy

Investment firms are required to point out that “past performance is not an indicator of future returns,” and several issues deserve scrutiny and debate. The controversy surrounding balloons has been cast as a free speech issue, but clearly engages complex national security concerns as well; that a guaranteed activity—in effect leafleting—could pose material risks to those living along the border. Nonetheless, I suspect that issue will end up before higher courts before it is finally resolved and the outright ban could well be overturned. The flawed media law, by contrast, has been almost universally panned as overreach by organizations interested in media freedom (for a sample, see the World Association of Newspaper and News Publishers and the UN Special Rapporteur on Freedom of Expression). On the other hand, that legislation has yet to be passed and is likely to be modified either in drafting or through subsequent litigation.

The assignment of National Assembly committee chairmanships and the creation of “task forces” within existing department might well reflect the prerogative of the ruling party majority but nonetheless reduce consultation or have a chilling effect on politics. And increasing polarization—although not an indicator of backsliding per se–may itself constitute a challenge to Korean democracy; I take up this issue in subsequent posts.

Yet viewed with the widest lens, recent derogations from democratic norms appear to have been more apparent under conservative than liberal governments and even some of those—particularly with respect to political rights and civil liberties—were marginal. More importantly, these derogations were ultimately checked. In the face of the corruption of the presidency of Park Geun-hye, it was not only civil society that served to check the president; the National Assembly and courts provided crucial institutional guardrails as well. Democracy requires vigilance, but Korea rightly deserves the reputation it enjoys as a successful, if sometimes fractious, new democracy.

Stephan Haggard is a Non-Resident Fellow at the Korea Economic Institute and the Lawrence and Sallye Krause Professor of Korea-Pacific Studies, Director of the Korea-Pacific Program and distinguished professor of political science at the School of Global Policy and Strategy University of California San Diego. The views expressed here are the author’s alone.

Photo from the Republic of Korea’s photostream on flickr Creative Commons.

Backsliding in Korea: Some Sources

Choi, Jang-Jip. 2020. “Reconsidering the Korean Democracy: Crisis and Alternative.” Journal of Korean Politics 29 (2): 1-26. In Korean. here

Croissant, Aurel, and Jung-eun Kim. 2020. “Keeping Autocrats at Bay: Lessons from South Korea and Taiwan.” Global Asia 15 (1). here

Croissant, Aurel, and Larry Diamond. 2020. “Introduction: Reflections on Democratic Backsliding in Asia.” Global Asia 15 (1). here

Croissant, Aurel. 2019. “Beating Backsliding? Episodes and Outcomes of Democratic Backsliding in Asia-Pacific in the Period 1950 to 2018.” Working Paper. here

Haggard, Stephan and Robert Kaufman. 2021. Backsliding: Democratic Regress in the Contemporary World. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. here

Haggard, Stephan and Jong-sung You. 2015. “Freedom of Expression in South Korea.” Journal of Contemporary Asia 45 (1): 167-179. here

Kang, Won-Taek. 2019. “Democracy in Crisis and Korean Politics.” Philosophy and Reality (철학과 현실) 123: 77-90. In Korean. here

Kang, Won-Taek. 2021. “The Crisis of Korean Politics and Representative Democracy.” Orbis Sapientiae (지식의 지평) Special Series 30: 1-14. In Korean. here

Kim, Jung. 2016. “The Current State of South Korea’s Democracy.” Journal of International and Area Studies 23 (2): 1-15. here

Kim, Jung. 2017. “South Korean Democratization: A Comparative Empirical Appraisal”

In Tun-jen Cheng and Yun-han Chu eds., Routledge Handbook of Democratization in East Asia. New York: Routledge. here

Shin, Gi-Wook. 2020a. “Korean Democracy is Sinking under the Guise of the Rule of Law.” Stanford Walter H. Shorenstein Asia-Pacific Research Center Commentary: 1-7. here

Shin, Gi-Wook. 2020b. “South Korea’s Democratic Decay.” Journal of Democracy 31 (3): 100-114. here

Wong, Joseph. 2019. “Democratic Resilience in South Korea and Taiwan” in Ursula Van Beek ed., Democracy under Threat, Challenges to Democracy in the 21st Century. Palgrave Macmillan: 199-220. here

You, Jong-sung, 2015, “The Cheonan Incident and the Declining Freedom of Expression in South Korea,” Asian Perspective, Vol. 39 (2): 195-219. here

(Compiled by Yeilim Cheong).