The Peninsula

Is Beijing Beginning to Ease the THAAD Boycott?

By Jenna Gibson

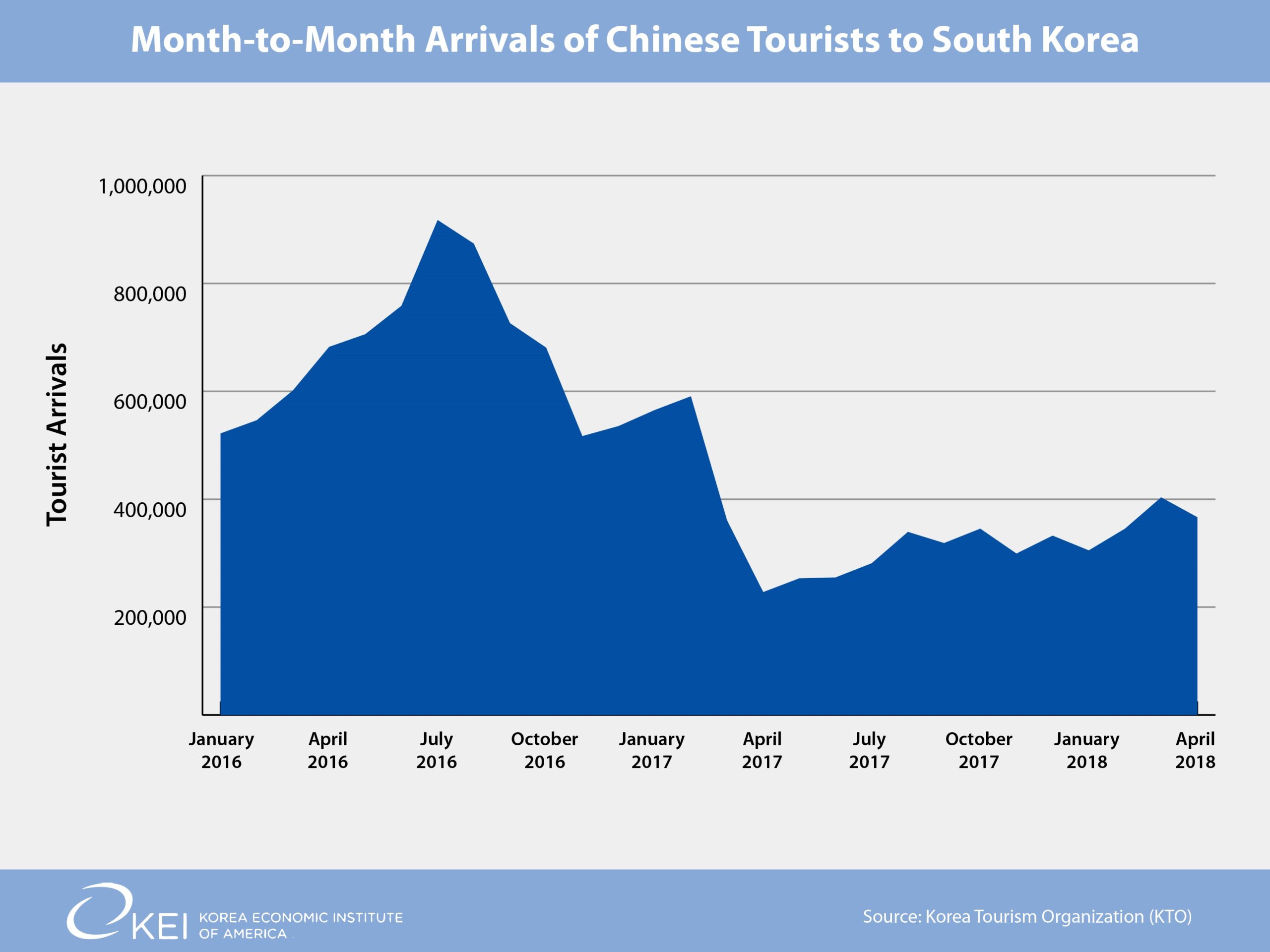

The number of Chinese tourists arriving in South Korea in March and April has increased year-on-year for the first time since February 2017. Is this a sign of a return to normal economic relations between South Korea and China?

Korean companies have been enduring a Chinese boycott of their products and services for two years now, fueled by Beijing’s anger over the Terminal High Altitude Aerial Defense (THAAD) missile defense system. The tourism industry was among the hardest hit, with the number of Chinese visitors to Korea dropping off a cliff last March. The numbers ended up decreasing as much as 70 percent year-on-year last summer.

The March numbers represent a small increase, reaching just above 400,000 when nearly 600,000 Chinese visitors used to arrive every month prior to the THAAD spat. The numbers declined in April to 366,600, but that is up from 277,800 Chinese tourists year-on-year and higher than every month since the boycott began other than the high in March. The fact that there is an increase at all after a full year of decreases is meaningful. The Chinese government was able to carefully control the number of tourists choosing to visit Korea last year to the point that in just a month, the number of visitors went from increasing 8 percent year-on-year in February, to decreasing 40 percent in March. So it would be naïve to think that this new increase, however small, didn’t involve the explicit or implicit permission of the government in Beijing. So while it is certainly too soon to declare a complete cease-fire in the THAAD row, signs are looking good for a gradual recovery.

In addition to the slight increase in tourism, there have been some other isolated cases that show progress. For example, in the entertainment industry, which had been hit hard by the boycott, a South Korean and Chinese company are partnering to join their two boy bands into a new combined group, which will feature a mix of Korean and Chinese members. The group is going to promote in Korea and China, which will provide an interesting litmus test for how the Chinese market re-opens to Korean content.

Not every industry is seeing a return to some amount of normalcy, however. For Lotte, the company that was specifically targeted for selling the land that THAAD eventually occupied, the Chinese market may be permanently off-limits. Last year, after the sale was announced, Chinese regulators suddenly raised various health and fire safety violations at many Lotte Mart locations across the country. According to the Chosun Ilbo, these shutdowns and an overall boycott of Lotte Mart stores caused their sales to plummet from 1.14 trillion won in 2016 to just 263 billion won in 2017. The paper estimates that Lotte’s combined losses from the spat surpass 2 trillion won.

Now, the conglomerate is throwing in the towel, selling off its assets in China and pulling out of the market completely. Clearly, even if the above cases are signs of a sincere easing of the Chinese government’s sanctions regime on South Korea, the relief didn’t come soon enough to keep Lotte from throwing in the towel and giving up on the Chinese market.

It is certainly too soon to tell if these promising signs in the tourism and entertainment industry represent an upward trajectory for Korean companies in China. After all, papers were running stories as early as May last year declaring the boycott at its end, and we can now clearly see that the devastating sanctions continued for many more months, causing billions of dollars in damage for many Korean companies. And even if this is finally the turning point toward a more friendly market for Korean goods and services in China – the recovery may be further delayed simply because Korean companies have seen what happens when you incur the wrath of Beijing – and no one wants to be the next Lotte.

Jenna Gibson is the Director of Communications at the Korea Economic Institute of America. The views expressed here are the author’s alone.

Photo from the Republic of Korea’s photostream on flickr Creative Commons.