The Peninsula

Increasing Korea’s Potential Growth Rate

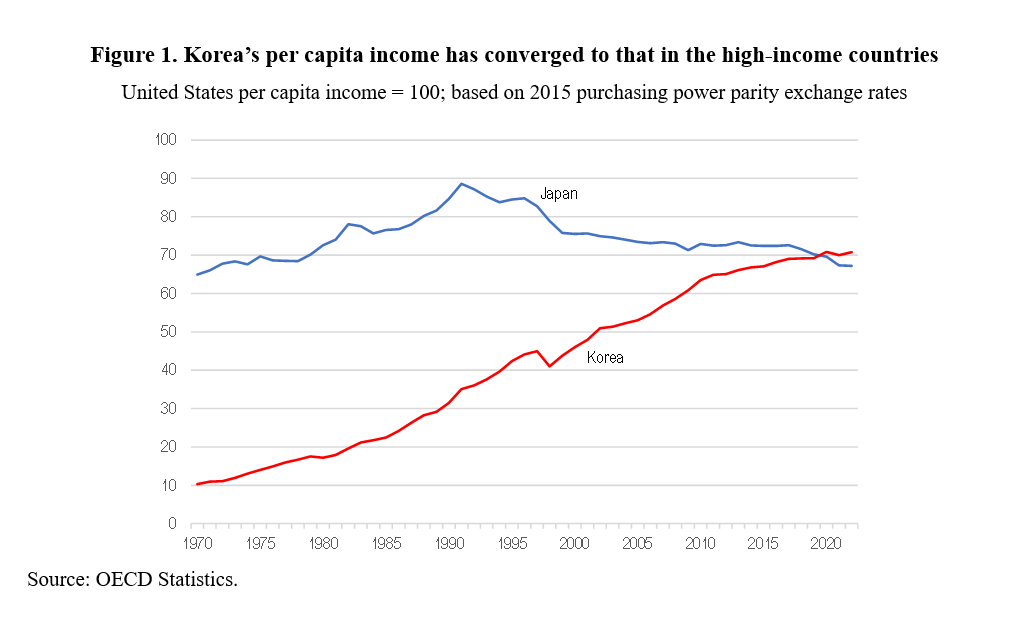

Korea’s development from one of the poorest countries in the world in the 1950s to a major industrial power has been exceptionally rapid. Per capita income increased from 10% of that in the United States in 1970 to 70% by 2020 (Figure 1). Moreover, Korea has surpassed Japan. Korea’s rapid transformation was achieved through effective policies, notably sound fiscal and monetary policy, high levels of investment in human and physical capital and an outward orientation that increased its share of world trade.

Korea’s potential growth rate has fallen close to the OECD average

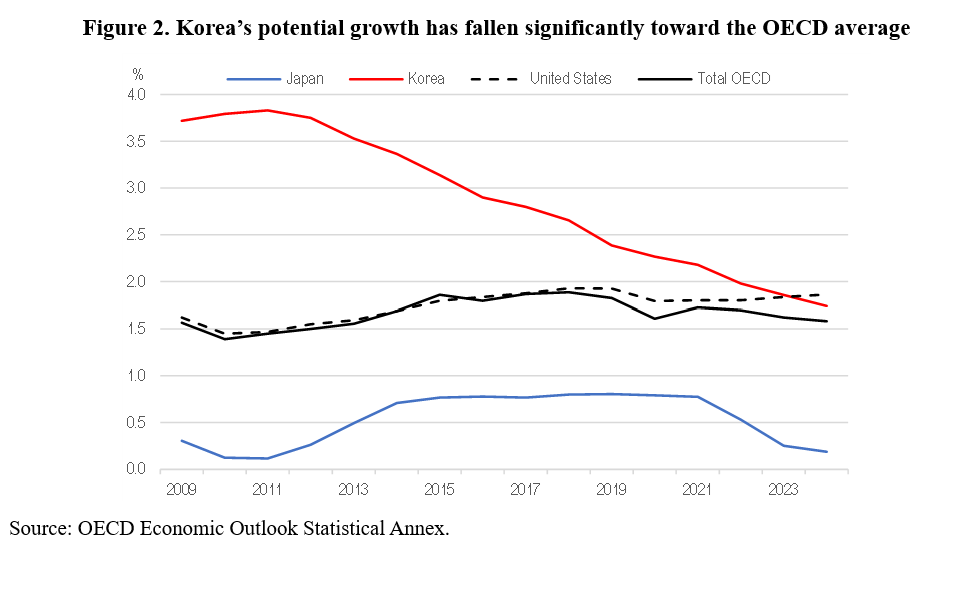

However, Korea’s more sluggish growth in recent years has raised questions about its ability to continue its convergence to the highest-income countries. Indeed, real GDP growth slowed from a 4.0% annual average growth rate over 2002-12 to 2.7% during the past decade. The rate of increase of potential output – defined as the level of output an economy would sustain at full capacity utilization and full employment – fell from 4.9% over 1997-2007 to 1.7% in 2024, according to OECD estimates (Figure 2). Korea’s potential growth rate is in line with the United States (1.9%) and the OECD average (1.6%)., while the IMF estimate is higher at 2.2% in 2023-24.

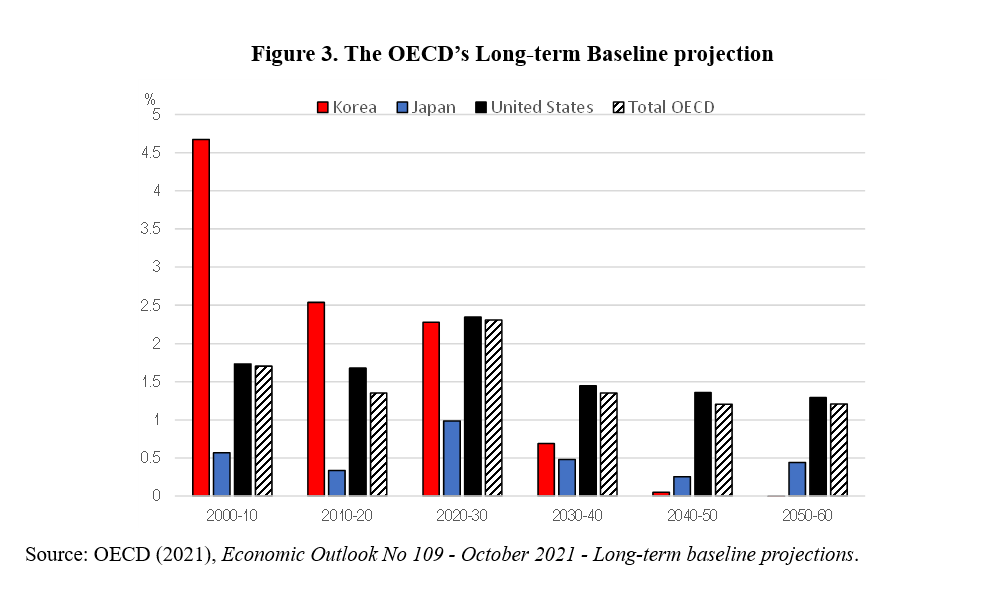

Potential output is estimated based on employment, total factor productivity and the capital stock. Rhee Chang-yong, governor of the Bank of Korea, stated at the IMF annual meeting on October 13, 2023, that “Around 2% is largely believed to be Korea’s potential growth rate, according to the trend of the population structure, but the general view is that the rate will gradually fall due to the aging society” (JoongAng Daily, 2013). The demographic challenge is serious; the total fertility rate – the average number of children a woman bears in her lifetime – dropped further to a record low of 0.7 in the second quarter of 2023. Moreover, the number of births in August 2023 fell 12.8% from a year earlier. Korea’s working-age population has been decreasing since 2017. The OECD’s Long-term Baseline projection showing Korea’s real GDP growth falling to zero in the decade 2050-60 reflects the demographic outlook (Figure 3).

Governor. Rhee stressed the importance of sustaining growth of at least 2% in the long term through structural reform to increase female employment and immigrant workers. Indeed, the female employment rate (for the 15-64 age group) was 58% in 2019 compared to the OECD average of 65%. Moreover, the share of Korea’s foreign population was less than 4% in 2021, well below the OECD average of 13%. Boosting youth employment is another priority: Korea’s employment rate for the 15-34 age group was 43% in 2021, well below the 53% OECD average.

Boosting potential growth also requires narrowing the productivity gap

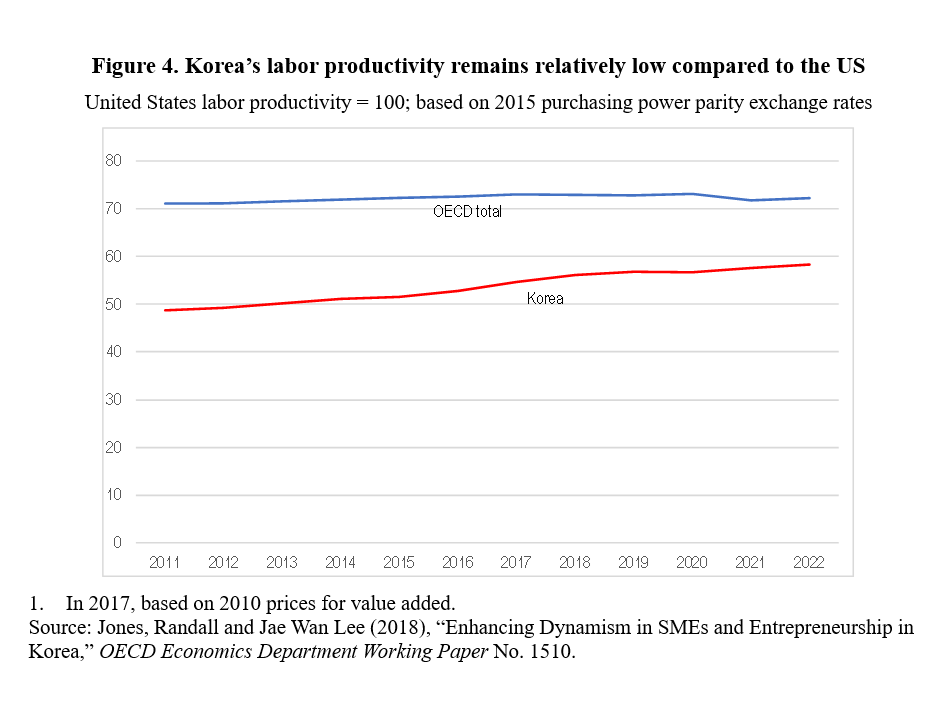

Korea’s labor productivity has edged up from 49% to 58% of the US level during the past decade (Figure 4). Further narrowing the gap would allow Korea’s per capita income to continue its convergence to the highest-income countries. Korea’s low productivity is somewhat surprising given its significant investments in innovation:

– R&D investment was 4.5% of GDP in 2018, the second highest among OECD countries. Korea’s business sector accounts for around three-quarters of R&D. A relatively large share of this investment is in information and communications technology (ICT).

– Korea is a leader in the number of patents in the fastest-growing digital technologies.

– The share of tertiary graduates among young people is the highest in the OECD area.

– Korea has the highest use of robots among OECD countries.

– Korea is the world leader in high-speed broadband.

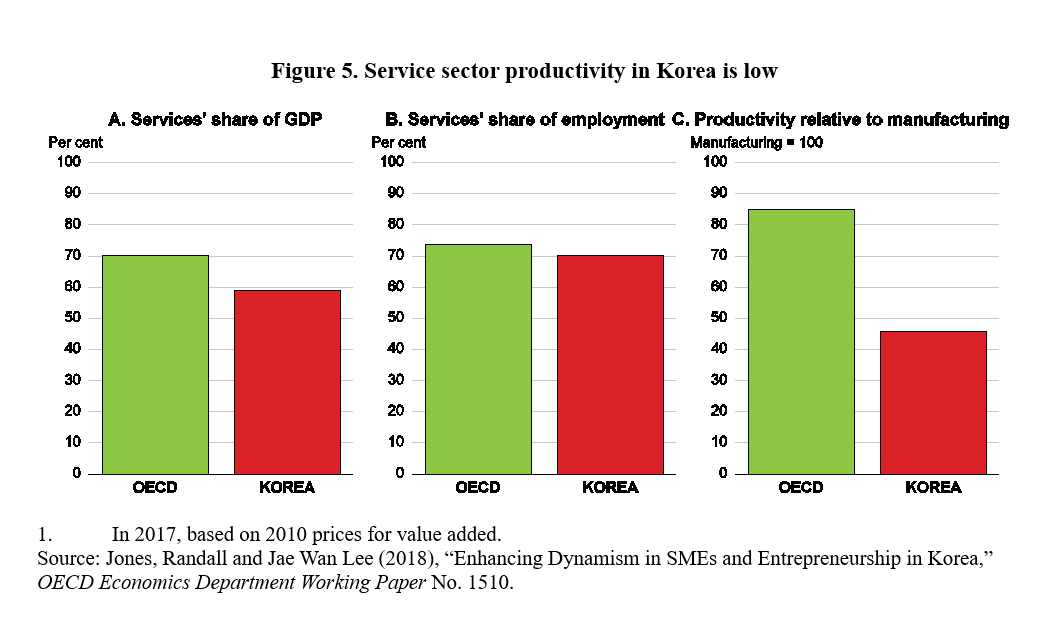

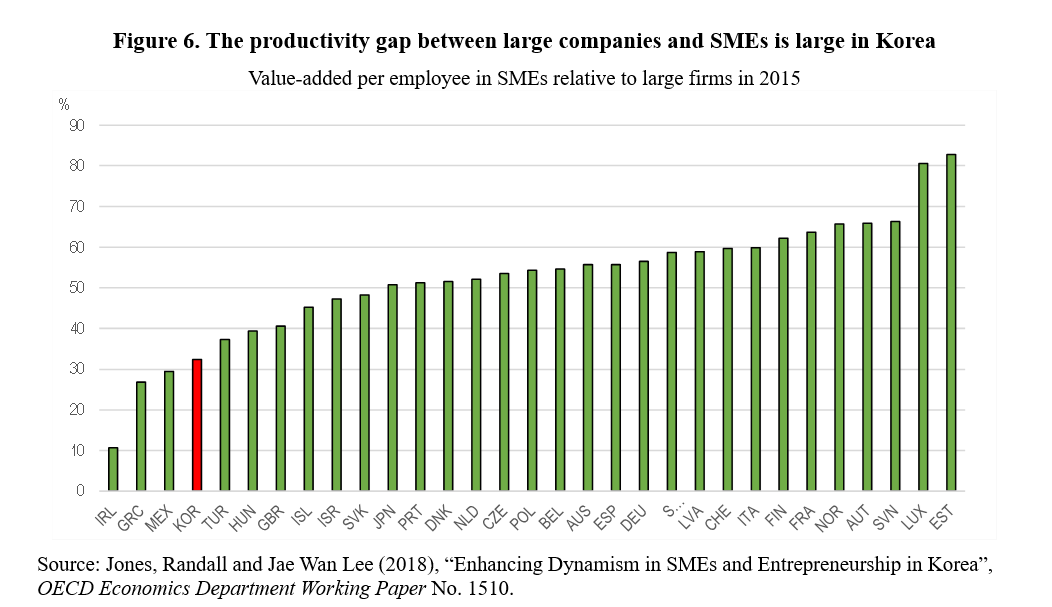

Korea needs to utilize these strengths to strengthen lagging sectors and reduce the polarization in the Korean economy. First, the productivity gap between manufacturing and services is relatively large. Labor productivity in the service sector in Korea is only 44% of that in manufacturing compared to an average of 84% in the OECD area (Figure 5). Second, there is a large gap between large companies and small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), reflecting the fact that around two-thirds of SME employment is in the service sector. Labor productivity in SMEs was only about one-third of that in large firms in 2015 (Figure 6).

Conclusion

Faced with the negative demographic headwinds resulting from the world’s lowest fertility rate, Korea needs a comprehensive strategy to maintain its potential growth rate. Measures to boost the fertility rate should be accompanied by policies to increase the returns from Korea’s large investment in innovation to narrow the large productivity gap with the highest-given countries. Measures to limit the decline in the labor force should focus on increasing the employment of young people, women and foreigners.

Randall S. Jones is a Non-Resident Distinguished Fellow at the Korea Economic Institute of America. The views expressed here are the author’s alone.

Photo from Craig Rohn’s photostream on flickr Creative Commons.